Nick Beams

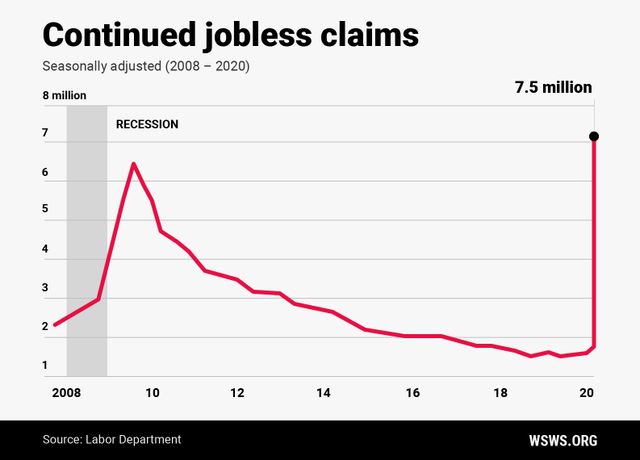

There could hardly have been a clearer expression of the deepening class divide. Yesterday the US Fed announced new financial stimulus measures of $2.3 trillion, as another 6.6 million American workers filed for unemployment benefits, bringing the total number to almost 17 million over the past four weeks.

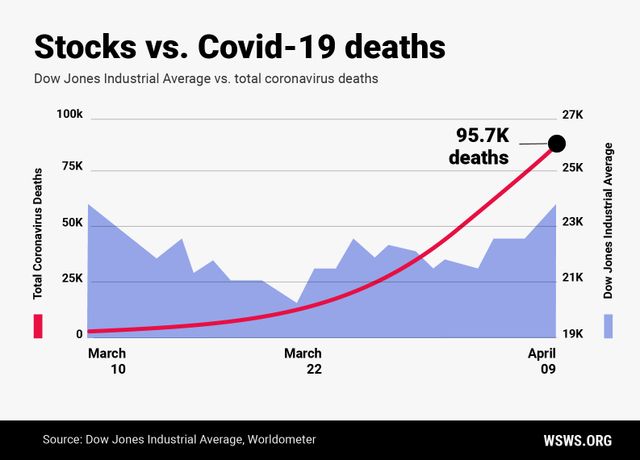

As workers face ever-greater hardship and the real economy goes further into slump, the financial markets celebrated on the announcement that money is still going to be pumped out, including through the purchase by the Fed of high-yield corporate junk bonds.

And there could be even more to come with Fed chairman Jerome Powell declaring during a Brookings Institution webcast that the central bank would use its powers “forcefully, proactively and aggressively.”

In this Oct. 1, 2019, file photo people wait in line to inquire about job openings with Marshalls during a job fair at Dolphin Mall in Miami. On Friday, Dec. 6, the U.S. government issues the November jobs report. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky, File)

In this Oct. 1, 2019, file photo people wait in line to inquire about job openings with Marshalls during a job fair at Dolphin Mall in Miami. On Friday, Dec. 6, the U.S. government issues the November jobs report. (AP Photo/Lynne Sladky, File)

The S&P 500 index, which is already up 25 percent from its mid-March lows, rose by another 1.4 percent, with big banks and real estate companies enjoying the biggest increases.

Earlier this week the International Labour Organisation published an update on the impact of the pandemic and lockdown measures on the global labour force. Official statistics lag far behind the actual situation, such is the speed of the economic plunge, and so the ILO had to use changes in working hours to make some estimate of the state of the labour market.

Using this approach, it said the COVID-19 crisis is expected to wipe out 6.7 percent of total working hours globally in the second quarter of this year—equivalent to 195 million full-time workers.

It said the eventual increase in unemployment for 2020 would depend on economic developments and policy measures but there was a “high risk that the end-of-year figure will be significantly higher than the initial ILO projection of 25 million.”

Currently 81 percent of the global workforce of 3.3 billion is affected by the full or partial workplace closures.

“Workers and businesses are facing catastrophe, in both developed and developing economies,” said ILO Director-General Guy Ryder.

The ILO found that 1.25 billion workers are employed in sectors of the economy identified as being at high risk of “drastic and devastating” increases in job losses, wage cuts and reductions in working hours.

“Many are in low-paid, low-skilled jobs, where a sudden loss of income is devastating.”

Emphasising the speed of the pandemic, the ILO noted that since its preliminary assessment on March 18 global COVID-19 infections had risen six-fold with an additional 47,600 people having lost their lives.

It said those still working, especially health workers, were most at risk together with workers in transport and essential public services.

“Globally there are 136 million workers in human health and social work activities, including nurses, doctors and other health workers, workers in residential care facilities and social workers, as well as support workers, such as laundry and cleaning staff, who face serious risk of contracting COVID-19 in the workplace.”

While the ILO did not make the point, those risks have elevated to unnecessarily high levels because of the decades of savage cuts to health and hospital services, leaving staff without necessary protective equipment. The resources of society have been siphoned to its upper echelons via the mechanisms of financialisation that have boosted the stock market.

There are around two billion people working informally, mainly in less developed economies, and tens of millions of them are now being directly affected by the pandemic. Informal workers, the report said, lack basic protection, are disadvantaged when it comes health care but are also involved in areas that “not only carry a high risk of virus infection but are also impacted by lockdown measures.”

The ILO is clearly of the view that there is not going to be some kind of “snapback” or V-shaped recovery when the immediate effects of the pandemic pass.

Characterising the outlook as “highly uncertain,” it said the rapid and far-reaching developments that had already taken place “bring us into uncharted territory in terms of assessing labour market impacts and in forecasting the severity of the shock.”

Economic organisations and institutions around the world are offering forecasts but none of them has an accurate gauge either of the depth of the slump or its duration.

Speaking ahead of its spring meeting next week, International Monetary Fund managing director Kristalina Georgieva said; “We anticipate the worst economic fallout since the Great Depression.”

The IMF releases its economic forecast next Tuesday which Georgieva said would show how quickly the coronavirus had turned the year into one of deep downturn. There was no doubt 2020 would be an “exceptionally difficult” year.

The IMF head warned that low-income countries in Africa, Latin America and in Asia were at high risk.

“With weak health systems to begin with, many face the dreadful challenge of fighting the virus in densely populated cities and poverty-stricken slums,” she said.

The problems confronting these countries are being intensified by the operations of the global financial system. Right at the point where additional resources are needed, money is being withdrawn at a record pace, putting pressure on currencies and government budgets.

Over the two months, according to Georgieva, capital outflows from emerging economies have totaled more than $100 billion. This is more than three times the outflows at the start of the global financial crisis. The IMF has received calls for emergency assistance from more than 90 countries so far.

The dire economic situation in Europe was reflected in two forecast published on Wednesday

One of Germany’s major economic forecasting bodies warned that the economy would contract by 10 percent in the second quarter, double the size of the biggest quarterly drop during the global financial crisis.

The Banque de France has warned that the lockdowns aimed at trying to contain the spread of the virus are slicing 1.5 percentage points from the French growth rate for every two weeks they continue.

The Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) said an index designed to identify turning points in the economic cycle showed its biggest drop on record in March. But worse may be to come. The OECD said its latest index only reflected the current situation, not how long or how severe the contraction would be.