Vijay Prashad, Du Xiaojun & Weiyan Zhu

On March 31, 2020, a group of scientists from around the world—from Oxford University to Beijing Normal University—published an important paper in Science. This paper—“An Investigation of Transmission Control Measures During the First 50 Days of the COVID-19 Epidemic in China”—proposes that if the Chinese government had not initiated the lockdown of Wuhan and the national emergency response, then there would have been 744,000 additional confirmed COVID-19 cases outside Wuhan. “Control measures taken in China,” the authors argue, “potentially hold lesso[n]s for other countries around the world.”

In the World Health Organization’s February report after a visit to China, the team members wrote, “In the face of a previously unknown virus, China has rolled out perhaps the most ambitious, agile and aggressive disease containment effort in history.”

In this report, we detail the measures taken by the different levels of the Chinese government and by social organizations to stem the spread of the virus and the disease at a time when scientists had just begun to accumulate knowledge about them and when they worked in the absence of a vaccine and a specific drug treatment for COVID-19.

The Emergence of a Plan

In the early days of January 2020, the National Health Commission (NHC) and the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) began to establish protocols to deal with the diagnosis, treatment, and laboratory testing of what was then considered a “viral pneumonia of unknown cause.” A treatment manual was produced by the NHC and health departments in Hubei Province and sent to all medical institutions in Wuhan City on January 4; city-wide training was conducted that same day. By January 7, China CDC isolated the first novel coronavirus strain, and three days later, the Wuhan Institute of Virology (Chinese Academy of Sciences) and others developed testing kits.

By the second week of January, more was known about the nature of the virus, and so a plan began to take shape to contain it. On January 13, the NHC instructed Wuhan City authorities to begin temperature checks at ports and stations and to reduce public gathering. The next day, the NHC held a national teleconference that alerted all of China to the virulent novel coronavirus strain and to prepare for a public health emergency. On January 17, the NHC sent seven inspection teams to China’s provinces to train public health officials about the virus, and on January 19 the NHC distributed nucleic acid reagents for test kits to China’s many health departments. Zhong Nanshan—former president of the Chinese Medical Association—led a high-level team to Wuhan City to carry out inspections on January 18 and 19.

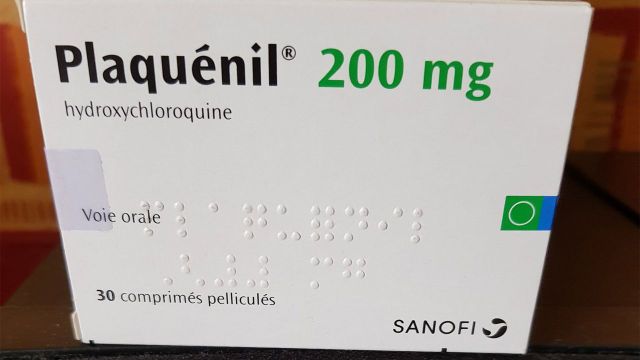

Over the next few days, the NHC began to understand how the virus was transmitted and how this transmission could be halted. Between January 15 and March 3, the NHC published seven editions of its guidelines. A look at them shows a precise development of its knowledge about the virus and its plans for mitigation; these included new methods for treatment, including the use of ribavirin and a combination of Chinese and allopathic medicine. The National Administration of Traditional Chinese Medicine would eventually report that 90 percent of patients received a traditional medicine, which was found to be effective in 90 percent of them.

By January 22, it had become clear that transport in and out of Wuhan had to be restricted. That day, the State Council Information Office urged people not to go to Wuhan, and the next day the city was essentially shut down. The grim reality of the virus had by now become clear to everyone.

The Government Acts

On January 25, the Communist Party of China (CPC) formed a Central Committee Leading Group for COVID-19 Prevention and Control with two leaders—Li Keqiang and Wang Huning—in charge. China’s President Xi Jinping tasked the group to use the best scientific thinking as they formulated their policies to contain the virus, and to use every resource to put people’s health before economic considerations. By January 27, Vice Premier of the State Council Sun Chunlan led a Central Guiding Team to Wuhan City to shape the new aggressive response to virus control. Over time, the government and the Communist Party developed an agenda to tackle the virus, which can be summarized in four points:

1. To prevent the diffusion of the virus by maintaining not only a lockdown on the province, but by minimizing traffic within the province. This was complicated by the Chinese New Year break, which had already begun; families would visit one another and visit markets (this is the largest short-term human migration, when almost all of China’s 1.4 billion people gather in each other’s homes). All this had to be prevented. Local authorities had already begun to use the most advanced epidemiological thinking to track and study the source of the infections and trace the route of transmission. This was essential to shut down the spread of the virus.2. To deploy resources for medical workers, including protective equipment for the workers, hospital beds for patients, and equipment as well as medicines to treat the patients. This included the building of temporary treatment centers—including later two full hospitals(Huoshenshan Hospital and Leishenshan Hospital). Increased screening required more test kits, which had to be developed and manufactured.3. To ensure that during the lockdown of the province, food and fuel were made available to the residents.4. To ensure the release of information to the public that is based on scientific fact and not rumor. To this end, the team investigated any and all irresponsible actions taken by the local authorities from the reports of the first cases to the end of January.

These four points defined the approach taken by the Chinese government and the local authorities through February and March. A joint prevention and control mechanism was established under the leadership of the NHC, with wide-ranging authority to coordinate the fight to break the chain of infection. Wuhan City and Hubei Province remained under virtual lockdown for 76 days until early April.

On February 23, President Xi Jinping spoke to 170,000 county and Communist Party cadres and military officials from every part of China; “this is a crisis and also a major test,” said Xi. All of China’s emphasis would be on fighting the epidemic and putting people first, and at the same time China would ensure that its long-term economic agenda would not be damaged.

Neighborhood Committees

A key—and underreported—part of the response to the virus was in the public action that defines Chinese society. In the 1950s, urban civil organizations—or juweihui—developed as way for residents in neighborhoods to organize their mutual safety and mutual aid. In Wuhan, as the lockdown developed, it was members of the neighborhood committees who went door-to-door to check temperatures, to deliver food (particularly to the elderly) and to deliver medical supplies. In other parts of China, the neighborhood committees set up temperature checkpoints at the entrance of the neighborhoods to monitor people who went in and out; this was basic public health in a decentralized fashion. As of March 9, 53 people working in these committees lost their lives, 49 of them were members of the Communist Party.

The Communist Party’s 90 million members and the 4.6 million grass-roots party organizations helped shape the public action across the country at the frontlines of China’s 650,000 urban and rural communities. Medical workers who were party members traveled to Wuhan to be part of the frontline medical response. Other party members worked in their neighborhood committees or developed new platforms to respond to the virus.

Decentralization defined the creative responses. In Tianxinqiao Village, Tiaoma Town, Yuhua District, Changsha, Hunan Province, Yang Zhiqiang—a village announcer—used the “loud voice” of 26 loudspeakers to urge villagers not to pay New Year visits to each other and not to eat dinner together. In Nanning, Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region, the police used drones to play the sound of trumpets as a reminder not to violate the lockdown order.

In Chengdu, Sichuan Province, 440,000 citizens formed teams to do a range of public actions to stem the transmission of the virus: they publicized the health regulations, they checked temperatures, they delivered food and medicines, and they found ways to entertain the otherwise traumatized public. The Communist Party cadre led the way here, drawing together businesses, social groups, and volunteers into a local self-management structure. In Beijing, residents developed an app that sends registered users warnings about the virus and creates a database that can be used to help track the movement of the virus in the city.

Medical Intervention

Li Lanjuan was one of the early medical doctors to enter Wuhan; she recalled that when she got there, medical tests “were difficult to get” and the situation with supplies was “pretty bad.” Within a few days, she said, more than 40,000 medical workers arrived in the city, and patients with mild symptoms were treated in temporary treatment centers, while those who had been seriously impacted were taken to the hospitals. Protective equipment, tests, ventilators, and other supplies rushed in. “The mortality rate was greatly reduced,” said Dr. Li Lanjuan. “In just two months, the epidemic situation in Wuhan was basically under control.”

From across China came 1,800 epidemiological teams—with five people in each team—to do surveys of the population. Wang Bo, a leader of one of the teams from Jilin Province, said that his team conducted “demanding and dangerous” door-to-door epidemiological surveys. Yao Laishun, a member of one of the Jilin teams, said that within weeks their team had carried out epidemiological surveys of 374 people and traced and monitored 1,383 close contacts; this was essential work in locating who was infected and treated as well as who needed to be isolated if they had not yet presented symptoms or if they tested negative. Up to February 9, the health authorities inspected 4.2 million households (10.59 million people) in Wuhan; that means that they inspected 99 percent of the population, a gargantuan exercise.

The speed of the production of medical equipment, particularly protective equipment for the medical workers, was breathtaking. On January 28, China made fewer than 10,000 sets of personal protective equipment (PPE) a day, and by February 24, its production capacity exceeded 200,000 per day. On February 1, the government produced 773,000 test kits a day; by February 25, it was producing 1.7 million kits per day; by March 31, 4.26 million test kits were produced per day. Direction from the authorities moved industrial plants to churn out protective gear, ambulances, ventilators, electrocardiograph monitors, respiratory humidification therapy machines, blood gas analyzers, air disinfectant machines, and hemodialysis machines. The government focused attention on making sure that there was no shortage of any medical equipment.

Chen Wei, one of China’s leading virologists who had worked on the 2003 SARS epidemic and had gone to Sierra Leone in 2015 to develop the world’s first Ebola vaccine, rushed to Wuhan with her team. They set up a portable testing laboratory by January 30; by March 16, her team produced the first novel coronavirus vaccine that went into clinical trials, with Chen being one of the first to be vaccinated as part of the trial.

Relief

To shut down a province with 60 million inhabitants for more than two months and to substantially shut down a country of 1.4 billion inhabitants is not easy. The social and economic impact was always going to be very great. But, the Chinese government—in its early directives—said that the economic hit to the country was not going to define the response; the well-being of the people had to be dominant in the formulation of any policy.

On January 22, before the Leading Group was formed, the government issued a circular that said medical treatment for COVID-19 patients was guaranteed and it would be free of cost. A medical insurance reimbursement policy was then formulated, which said that expenses from medicines and medical services needed for treating the COVID-19 would be completely covered by the insurance fund; no patient would have to pay any money.

During the lockdown, the government created a mechanism to ensure the steady supply of food and fuel at normal prices. State-owned enterprises such as China Oil and Foodstuffs Corporation, China Grain Reserves Group, and China National Salt Industry Group increased their supply of rice, flour, oil, meat and salt. All-China Federation of Supply and Marketing Cooperatives helped enterprises to get direct connection with farmers’ cooperatives; other organizations like China Agriculture Industry Chamber of Commerce pledged to maintain supply and price stability. The Ministry of Public Security met on February 3 to crack down on price gouging and hoarding; up to April 8, the prosecutorial organizations in China investigated 3,158 cases of epidemic-related criminal offenses. The state offered financial support for small and medium-sized enterprises; in return, businesses revamped their practices to ensure a safe working environment (Guangzhou Lingnan Cable Company, for instance, staggered lunch breaks, tested the temperature of workers, disinfected the working area periodically, ensured that ventilators worked, and provided staff with protective equipment such as masks, goggles, hand lotion, and alcohol-based sanitizers).

Lockdown

A study in The Lancet by four epidemiologists from Hong Kong show that the lockdown of Wuhan in late January prevented the spread of infection outside Hubei Province; the major cities of Beijing, Shanghai, Shenzhen, and Wenzhou, they write, saw a collapse in numbers of infections within two weeks of the partial lockdown. However, the scholars write, as a consequence of the virulence of COVID-19 and the absence of herd immunity, the virus might have a second wave. This is something that worries the Chinese government, which continues to be vigilant about this novel coronavirus.

Nonetheless, the lights of celebration flashed across Wuhan as the lockdown was lifted. Medical personnel and volunteers breathed a sigh of relief. China had been able to use its considerable resources—its socialist culture and institutions—to swiftly break the chain.