Vijay Shankar

The Shangri-La Dialogue, an Asian security summit held annually in Singapore, took place between 31 May-2 June this year. And, in a grand affirmation of design, its director general declared, “It is a unique meeting where ministers debate the region’s many pressing security challenges, engage in bilaterals and come up with fresh solutions together”. Yet the central and perhaps the only theme that loomed was the strategic road taken by China over the years: from ideology and foment to growth, revision, and regional domination. China’s participation was remarkable not just for the level of its delegate, the defence minister General Wei Shenghe, but also for the resolve to hold sway in the region that he so candidly declared. Unfortunately, it was not debate that defined deliberations but the impending pay-back for a “hundred years (since the opium wars) of humiliation” and the probability of a breakdown of the status-quo without an alternative.

That China’s stunning growth had shifted the strategic centre of gravity of the world is a reality; however, what startled was China’s unabashed announcement that the world will now have to “adapt to its success” and it can no longer be subjected to the “iniquities” of the past. A clear statement of disaffection with the current order and a burial of Deng’s strategy to “hide-power-and-bide-time.”

What is emerging is that an international order on China’s terms would amount to little else but a 'monocracy' since China has taken no step to convince through actions that its objectives are directed towards a more even-handed order, and that its methods are neither authoritarian nor mercantilist. Their dealings in Sri Lanka, Kenya, Guinea, or for that matter, engagement with the World Trade Organisation (WTO) since 2001 are stark reminders of just the opposite.

It may be recalled that in 2001, China’s trade accounted for 4 per cent of world trade. At the time, the western world was faced with high cost labour, an aging population, and low-productive democracy, which made economic sense to turn to China. Today, while those conditions remain, the situation in China has changed: labour is no longer cheap. Today, China’s share of world trade has almost tripled to 11.8 per cent. Concessions negotiated when it joined the WTO are no longer politically tenable; neither for those that bestowed this largesse nor for others in competition. A regime more consistent with present-day China’s state of development would appear the order of the day. Indeed, it may be argued that the fall-out of the petrodollar system that boosted the US Dollar as the globally accepted reserve currency creates an immediate and persistent artificial demand for it. This, quite unfairly, benefits only the US and the oil cartel, making it a distressing paradox that calls for reforms to the WTO.

In the context of military power, China’s defence expenditure is the second largest in the world; its policies carry weight, often provoke, arouse suspicion, and are invariably acted upon from a security perspective. China’s “right to build infrastructure and deploy defensive capabilities on the islands and reefs in the South China Sea,” is emphasised in the latest iteration of its Defence White Paper. So, its strategies of Anti-Access/Area Denial (A2/AD), developing the 'Assassin’s Mace', creation of confounding Air Defence Identification Zones (ADIZs), and activities in the South China Sea (SCS) to create a 'maritime great wall' are symptomatic not just of safeguarding interests, but to dominate the region with no legitimacy. Friction is mounting in these waters and China is not inclined to resolve these disputes with the other stakeholders.

Neither international law nor the United Nations Convention on the Laws of the Sea (UNCLOS) seem to evoke any reverence, whether it be their 'Nine-Dash Line', military bases on the Mischief Reef (Philippines' EEZ), artificial islands along the way, or the dispute over the Paracel and Spratly Islands. Nevertheless, China insists that the situation in the SCS is stable, citing, intriguingly, the “100,000 ships” that sail through every year as evidence that there is no threat to trade while denouncing “countries outside the region that have come to the SCS to flex muscles in the name of freedom of navigation.” Such power declarations hardly lend itself to the idea of a China that can be relied and respected to support a durable regional environment. China, however, remains ostensibly oblivious to the fact that the strategic pivot of the world has long shifted to the Indo-Pacific, making stakeholders in these waters from far beyond the region..

Meanwhile, global stresses have built-up over multiple issues relating to cyber espionage, human rights, and 5G technologies. China would appear to have regressed in terms of political openness, military bullying, creation of a Sino-centric economic bloc, and a disdainful approach to international law. This strategic orientation will probably augur well for China’s aspirations but hardly so for global prospects.

China’s Belt and Road Initiative (BRI) is ambitious and comes with its share of controversies. It has also rapidly increased China's overall risk profile. Added to China's internal debt, excess capacity, increasing labour costs, and high ratio of investment to growth, the prospects of increased recurrence of a Hambantota are portentous. The Centre for Global Development (CGD) has concluded that Beijing, encourages dependency using opaque contracts, rapacious loan practices, and corrupt deals that mire countries in debt to undercut their sovereignty. Their infrastructural dealings with Djibouti, Kyrgyzstan, Laos, the Maldives, Mongolia, Montenegro, Pakistan, and Tajikistan are stark reminders of how predatory economic policies work. Malaysian Prime Minister Mahathir had in 2018 announced the shelving of two major projects, part of China’s signature BRI, to avert falling into an obsequious debt trap. As recently as 15 July, Dawn, a Pakistani newspaper, reported on China's reminder to Pakistan of the grave consequences of reneging on the earlier signed China Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC) contract.

Now, what could all this mean?

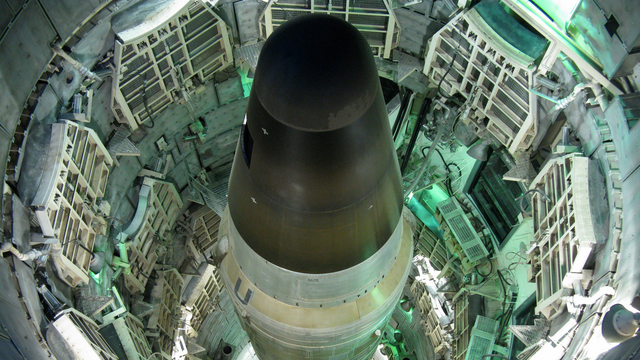

A Titan II nuclear missile [credit: US Department of Defense]

A Titan II nuclear missile [credit: US Department of Defense] President Ronald Reagan and Soviet Union General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev sign the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty in the East Room of the White House, Dec. 8, 1987 [credit: White House]

President Ronald Reagan and Soviet Union General Secretary Mikhail Gorbachev sign the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty in the East Room of the White House, Dec. 8, 1987 [credit: White House]