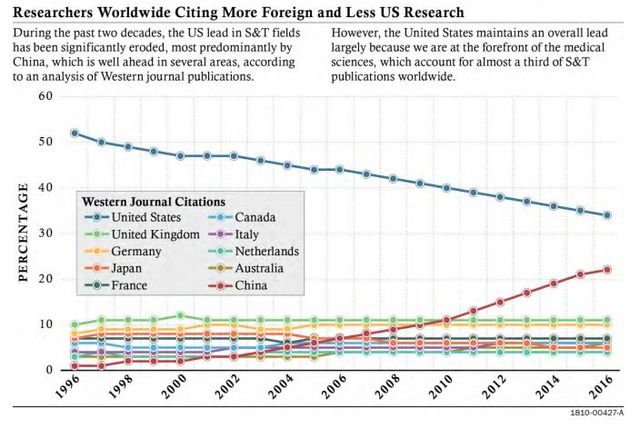

Jón Karl Stefánsson

Since 2015 Venezuela has endured gruesome economic hardships. Inflation rates have spiraled out of control, and the public is facing a recession that is tearing the country apart. Now, Venezuelans not only face economic turmoil, but also direct military aggression. A sane response of anyone who wishes to help Venezuelans through these troubles is to try to understand why this is happening.

Unfortunately, not all opinion pieces and news articles are honest in their approach. In fact, most media outlets seem to regurgitate the same poor and factually erroneous narratives, leaving the public ill-informed. It is necessary to address some common falsehoods that have been circulating concerning the economic situation in Venezuela and to highlight important facts that have largely been omitted from the common narrative.

Venezuela’s economic problems did not start with the Bolivarian revolution

One example of dishonest narratives in the pages of the Western media is that Venezuela’s economic problems are caused by the policies Hugo Chavez and Nicolas Maduro. These men are depicted as despots who have ruined a formerly healthy economy and as the culprits of Venezuela’s current crises. Latent in such narratives is the sometimes-unuttered, sometimes yelled, assumption that the Venezuelan economy was in good shape prior to the public election of Chavez in 1998. This is certainly not true.

Venezuela economic crisis started more than 35 years ago. From 1983 to 1998 real income fell by 14 percent, in a society that was already extremely corrupt and unequal (Corrales, 1999).According to data from the Inter-American Development Bank, 68 percent of Venezuelans lived below the poverty line in 1998. That same year the unemployment rate was 11.2 percent, and the inflation rate was 35.8 percent. This was a year before Chavez took office as president and before any economic sanctions and pressures from the West started.

After Chavez was elected president the economy strengthened considerably for three years, despite country being hit by massive flooding and landslides in December 1999. The inflation rate fell to 12.5% in 2001 and the poverty rate was successfully lowered to 39% (Weisbrot, 2008). The Bolivarian economic policies followed by the Chavez government were lifting Venezuelans out of poverty when Venezuela fortunately not being targeted for regime change.

What did cause the first downturn of Venezuela’s economy was not its progressive policies, nor Chavez’s alleged despotism, but a major attempt at a CIA assisted military coup d’état in 2002 and a subsequent violent shutdown of the country’s oil industry. That coup left the country in turmoil despite being unsuccessful.Prior to 2003, the government did not exert control over the oil industry. The oil industry shut-down in 2002-2003 was orchestrated by the “Coordina Democrática”, an umbrella group of political parties, business federations and right-wing unions that pursued to overthrow the government by non-electoral means.We shall examine that coup attempt in more detail later, but we must note that this overt policy of the Venezuelan right-wing and its supporters in the US was conducted in a climate of increasingly positive standards of living, especially for the poor.

Unfortunately, the failure of that coup attempt was not the end, but only the beginning of attempts to force Venezuela to steer from its policies. From that point to the present, Venezuela’s progressive policies were targeted by ever more sinister means and attempts at un-democratic takeover.

A recession followed the coup in 2002 that lasted for two years. But the country bounced back and in 2005, the Venezuelan economy grew by 9,4%, the highest in Latin America. Inflation rates lowered to 15.3% (Wilpert, 2005). In 2012, Venezuela was the most equal society in Latin America in terms of wealth distribution (BBC, 2012). According the CNN, “In 2011, the Gini coefficient — which measures income inequality –was .39, down from nearly .50 in 1998, according to the CIA Factbook. That is, equality in Venezuela was better than in the US and only behind Canada in the Western Hemisphere”. (Voigt, 2013). Thus, despite real and aggressive attempts at sabotage, the Chavéz government managed to put into place policies that aided the poor and, at the same time, strengthened the economy.

Simplistic explanations with glaring omissions

A common theme in current news stories regarding Venezuela’s crisis is that its cause can be found solely in the “economic mismanagement, corruption and political oppression” of Chavéz and Maduro (Laya, 2019). Such claims are supported with examples of the “Dutch syndrome”, where a country becomes to reliant on one commodity (Venezuela is very reliant on oil), on overspending on social programs, heavy lending and corruption. These claims might be open for reasonable debate if Venezuela had in any real sense been allowed to operate in peace. But nothing could be further from the truth.

Oil manipulation

A factor too seldom included in the common narrative on Venezuela’s economic crash is the apparently intentional meddling of oil prices by Saudi Arabia and its allies that apparently aimed at hurting Iran (Cooper, 2014) as well as other oil dependent countries such as Venezuela and Russia. Starting in 2014, Saudi Arabia started to flood the market with cheap oil. Despite this hurting even Saudi Arabia itself, this overproduction of oil had drastic effects. The price of oil went down from $110 per barrel to $28 in two years (Puko, 2016). This plummeting of oil prices had immediate negative effects on the Venezuelan state budget, as well as on other oil dependent countries, leaving Venezuela cash-starved. It is true that the country was indeed over dependent on one resource, and it has a serious corruption problem. But it is hard to see how the government of Venezuela could have managed to deal with such a huge blow to its economy amidst serious sanctions and economic sabotage that already plagued the country. A right-wing government would not have fared better in these circumstances. Instead of showing understanding to its problems, this crisis was used to denounce the Maduro government and to promote propaganda that increased the possibility of violent foreign and internal aggression.

The effects of economic sanctions

Economic sanctions directed by the most powerful military- and economic powers can cripple any economy. Even relatively mild sanctions can have serious consequences for the target economy. It has been found that the imposition of economic sanctions decreases the target state’s real per capita GDP growth rate by 25 to 30 percentage points on average with effects lasting for at least 10 years. More serious sanctions produce more serious effects (Neuenkirch, 2015).Furthermore, economic sanctions have been found to seriously worsen economic inequality and widen the poverty gap in target countries, in effect hitting the poorest people in the target countries hardest (Afersorgbor & Mahadevan, 2016; Mulder, 2018).

For example, in 1993, Serbia was singled out for economic sanctions that lasted until 2001. The sanctions had devastating effects on the public, making more than half the population of the country poor, unemployed, or displaced as refugees (Garfield, R. 2003). In Iraq, the economic sanctions imposed on the country in August 1990 and extended following the 1991 Persian Gulf War, lead to a decrease in GDP from $38 billion in 1989 to $10.8 billion in 1996. Per capita GDP declined over 75%, leading to devastating effects for the public. According to a report by Bossuyt (2000), the transportation, power and communication infrastructure were not rebuilt during the period, the industrial sector was in shambles, and agricultural production suffered greatly due to the sanctions. The “purchasing power of an Iraqi salary by the mid-1990s was about 5 per cent of its value prior to 1990 …” and, as the United Nations Development Program field office recognized, “the country has experienced a shift from relative affluence to massive poverty …The previous advances in education and literacy have been completely reversed over the past 10 years” (ibid).

As should be obvious, economic sanctions have horrible effects on the economy of the targeted nations and their inhabitants. How strange it is that opinion pieces, editorials and news segments tend to completely ignore that the overbearing barrage of economic sanctions directed against Venezuela might be a factor in the current crisis in its economy. Journalists that fail to address this cannot and should not be taken seriously.

The crash in Venezuela is directly linked to economic sanctions

In 2006, the first economic sanctions against Venezuela were put in place by Venezuela’s most important trading partner and,apparently, its worst enemy, the U.S. At first, these were directed against single individuals, but gradually these have evolved into hard and serious sanctions on all Venezuela.

The US House of Representatives passed the Venezuelan Human Rights and Democracy Protection Act (H.R. 4587; 113th Congress) on May 28, 2014. It applied economic sanctions against Venezuelan officials who were alleged to be involved in the mistreatment of protestors during the 2014 Venezuelan protests.

In December that year, the U.S. Congress passed S. 2142 (Venezuela Defense of Human Rights and Civil Society Act of 2014). The bill directed the President to impose sanctions against “any person, including any current or former official for the government of Venezuela or person acting on behalf of that government” who the US Congress would deem as responsible for human rights abuses or “knowingly materially assisted, sponsored or provided significant financial, material or technological support for, or goods or services in support of, the commission of such acts” (Poling et al., 2014). When the US Congress passed the bill, U.S. businesses raised concerns that the legislation could provide an incremental step towards broader sanctions against the Venezuelan economy, including the country’s oil industry despite being introduced as targeting individuals (ibid).

On March 9, 2015, the Obama Administration signed and issued a Presidential order. In it, Venezuela was declared a threat to US national security and sanctions were ordered against Venezuelan officials. How Venezuela was a threat to the United States was not explained. The order was strongly denounced by the Community of Latin American and Caribbean Sates for its “unilateral coercive measures against International Law” (Tejas, 2015). Ernesto Samper, the Secretary-General of the Union of South American Nations, deemed the order as an attempt to disrupt the democratic process in Venezuela.

The Trump Administration greatly escalated the economic pressures started by the Obama Administration. These included financial sanctions against the Venezuelan government and aggressive measures against the oil industry. The additional sanctions on Venezuela that were imposed with Executive Order 13808 on August 24, 2017 were nothing less than an act of aggression against the Venezuelan economy and its people. It specifically bars revenues from Venezuela’s state oil company to paid from the US, bars the Venezuelan government from selling bonds, and even bars the state from receiving loans. These sanctions were designed to prevent Venezuela’s own money from entering Venezuela.Note that all the Venezuelan governments’ outstanding foreign currency bonds are governed under New York State law,and one of Venezuela’s major government assets, the state oil company, is based in Texas. So barring all profit flow from that company is crippling for Venezuela (Ellner, 2019).

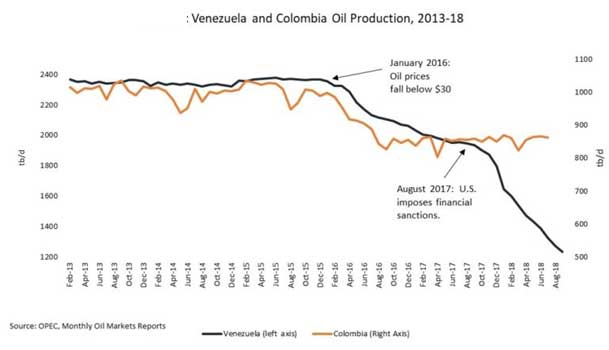

The US economic sanctions have indeed had devastating effects on the Venezuelan economy. Francisco Rodriguez, Venezuelan economist and a long-time critic of the Venezuelan government, presented clear evidence that since 2015, and especially after the sanctions imposed by the Trump administration in 2017, Venezuela’s oil production dropped much faster than had been predicted. According to Rodriguez, after the sanctions made it illegal for the Venezuelan government to obtain financing from the US, Venezuelan production fell by 37%, much more than the 6-13% decline that had been predicted. Rodriguez calculated that the difference in total revenue between the “sanctions” and “no sanctions” case over one year was about $6 billion. That sum is 133 times larger than what the UNHCR has appealed for in aid for Venezuelan migrants. Rodríguez summed up the main cause of Venezuela’s economic implosion as follows: “The fall in oil production began when oil prices plummeted in early 2016 but intensified when the industry lost access to credit markets in 2017” (Rodríguez, 2018).

As Rodriguez explained “To understand the magnitude of this effect, consider how much Venezuela would be earning in oil export revenue today if production had not declined. Were the country selling as many barrels to the rest of the world today as in 2015, it would have exported $51bn in oil this year. By contrast, Venezuela will sell only $23bn of oil internationally in 2018. And, if the slide in production continues, only $16bn in 2019. We can safely say that if the country was receiving $28bn more in yearly export revenue than it does today, it would have experienced a much smaller decline in living standards than it saw.”

The US issued yet another economic sanction on Venezuela on January 28 this year. This time specifically focusing on “persons operating in Venezuela’s oil sector”, especially on Petroleos de Venezuela (PDVSA). The press release announcing these new economic sanctions even specify that the US will “continue to take concrete and forceful actions against those who oppose the peaceful restoration of democracy in Venezuela” adding that the US “stands with interim President Juan Guaido”, an un-elected man (US dep. of State, 2019). This means that not only is the US arbitrarily sanctioning another country’s state assets and intentionally hurting its economy, it is directly involving itself in the internal affairs on another country, which is illegal under international law.

The severe attacks on Venezuela´s economy have been followed by US allies. Recently, the Bank of England refused to return $1.2 billion in gold reserves after lobbying from National Security Adviser John Bolton and Secretary of State Michael Pompeo (Laya, Bronner and Ross, 2019).

Indeed, these sanctions have been described “illegal and could amount to ‘crimes against humanity’ under international law” by Alfred de Zayas, former special rapporteur to the UN. According to de Zayas, the US is engaging in “economic warfare” against Venezuela that results in hurting the economy and killing Venezuelans (Selby-Green, 2019). As the sanctions seem to be means to starve the population of Venezuela and deliberately cripple the economy in order to achieve political aims, these acts can rightly be described as terrorism.

It is very doubtful that any economy would survive such violent sanctions. Unfortunately, the sanctions are only one part of the extensive sabotage that have been done towards the Venezuelan economy and society. An even bigger threat to Venezuela’s economy than US lead sanctions has been the conspicuous acts of the internal enemies of Venezuela’s government and its progressive Bolivarian policies.

Internal subversion

Ever since 1999, the Venezuelan government has been under constant attacks from the very rich and powerful elite of business oligarchs who hate Bolivarian politics with a passion. These oligarchs have been supported by the US, as well as far right groups in the hemisphere, not least in Colombia.

The first serious coup attempt took place in April 2002. It started with a general strike called by unions for the state oil company, PDVSA, which was followed by protest marches through Caracas. As protests neared the Miraflores palace, a massacre took place where 16 people were killed, 7 policemen and 9 civilians. Within hours, the military high command had arrested Chavéz and put in his place Pedro Carmona, the head of Venezuela’s largest business association. This presidency lasted 48 hours. In that short period Carmona, dissolved Congress and cancelled the newly approved constitution of Venezuela. Scores of people were imprisoned, and a military state was put in place. However, thousands of demonstrators and military personnel opposed to Carmona’s rule managed to reverse the coup. According to Bellos (2002),the Bush administration “was left with some eggs on its face. Unlike Latin American countries, which voiced concern that the coup had forsaken democratic principles, the US showed no remorse at Mr. Chavez’s removal”.

The narrative of exactly what happened is still very partisan, but the coup attempt had been organized for at least 9 months by a group of businessmen, military officers and various opposition figures in Venezuela. Keeping in mind how long this coup attempt was planned, it is hard to take seriously claims that the demonstrations and the massacre that occurred in the early hours of April 11, followed by the arrest of Chavez and other political figures by elements of the Venezuelan military were unrelated to these plans. Private media outlets reported with dishonesty about what happened that day (see Wilpert, G. 2009) and were therefore complicit in the coup attempt.

Although the extent to which institutions in the US were involved in the coup attempt, US officials knew it was going to take place. In 2004, declassified intelligence documents showed that the Central Intelligence Agency was aware that dissident military officers and opposition figures in Venezuela were planning a coup against President Hugo Chávez in 2002, well in advance. Parts of the document reads as followed: “disgruntled senior officers and a group of radical junior officers are stepping up efforts to organize a coup against President Chávez, possibly as early as this month…” It stated that Chávez and 10 senior officers were targeted for arrest and the plotters would try to “exploit unrest stemming from opposition demonstrations slated for later this month” (Forero, 2004).

In November 2013, a document titled “Plan Estratégico Venezolano” or “Stratetic Venezuelan Plan” that was written in June that same year, surfaced after suits from attorney Eva Golinger (2013). The document highlighted a plan by representatives of the United States, Colombia and the oligarchs in Venezuela to undermine the economy of Venezuela as part of removing Maduro. The document was prepared by the “Democratic Internationalism Foundations” which is headed by ex-Colombian president Alvaro Uribe, and also the “First Colombia Think Tank” and the US Consulting firm, FTI Consulting.

The document is a very sinister read. It outlines a strategic plan to destabilize Venezuela by various means. For example, it details a strategy to sabotage the electrical system in Venezuela, “maintain and increase the sabotages that affect public services” and “increase problems with supply of basic consumer products”. For propaganda, the authors propose “perfecting the confrontational discourse of [opposition candidate] Henrique Capriles” and generate “emotion with short messages that reach the largest quantity of people and emphasize social problems, provoking social discontent”. More seriously, the authors propose to create “situations of crisis in the streets that will facilitate US intervention, as well as NATO forces, with the help of the Colombian government” adding “whenever possible, the violence should result in deaths or injury”. The document recommends “a military insurrection” against Venezuela with “contacting active military groups and those in retirement to amplify the campaign to discredit the government inside the Armed forces… It’s vital to prepare military forces so that during a scenario of crisis and social conflict, they lead an insurrection against the government, or at least support a foreign intervention or civil uprising” (Golinger, 2013).

The plan was developed during a meeting between the three organizations as well as leaders of the Venezuelan opposition, including Maria Corina Machado, Julio Borges and Ramon Guillermo Avelado, expert in psychological operations J.J. Rendon and the Director of the US Agency for International Development (USAID) for Latin America, Mark Feierstein.

One must ask, how many such plans have been put in place since, but not exposed? The actions and dialogue of these oligarch show just how low they are ready to sink in order to oust a democratically elected government.

The opposition in Venezuela has been very violent and showed complete disregard for democratic principles. For example, in 2014 Venezuela was hit by a big wave of demonstrations following the outcome of the 2013 presidential elections, where Nicolas Maduro won by a small margin, 50.6%. During this time of unrest opposition political figures such as Leopoldo Lopéz, who had also been involved in the 2002 coup attempt, and María Corina Machado, launched a campaign to remove Maduro from office. The plan was named “La Salida” (the exit) and had the intent of having Maduro resign through protests. Machado stated publicly that “we must create chaos in the streets” (Carasik, 2014). At least 36 people died in the unrest following this statement. The opposition predictably blamed the government for these deaths. But considering that the deaths included several security forces and pro-government civilians and others were apparently non-affiliated, that statement must be contested (see Hart, 2014).

Recently, an organization called “Democratic Unity Roundtable” seems to have been coordinating acts of violence against those who are identified as pro-Chavista (Joubert-Ceci, 2017).This group was formed in 2008 to unify opposition Chavéz and can be viewed as the successor of the CoordinadoraDemocrática. The violent protests centered around a call by Maduro to a vote on a Constituent Assembly to rewrite the constitution. Despite having called for the Assembly themselves, the opposition refused to enter dialogue, demanding the presence of the Vatican. But even Pope Francis announced that the dialogue had failed because the opposition would not participate (Nelson, 2017). Instead, the opposition rallied anti-Maduro demonstrators to start a spree of violence that left at least 100 dead (ibid). According to the Canadian Peace Congress of 2017, “if an attempt at internal counter-revolution fails, plans are being put in place for direct military intervention by the United States, possibly under the cover of the Organization of American States (OAS)” (ibid). It is at least clear that the opposition is thoroughly un-democratic in their planning’s and actions but are still supported by Western powers.

To report that the economy of Venezuela is in turmoil solely because of Maduros “socialistic” policies, while ignoring the very serious consequences of economic sanctions, oil price manipulations, and internal sabotage is deliberate denial of facts, is propagandistic journalism, is absurd. Informed discussions about the effects and costs of progressive social programsmay be interesting and useful theoretical exercises.But as distortions and denials of historic facts, emotional attacks on Venezuela’s government should be seen as the propaganda, designed to manipulate American, Canadian and European populations into supporting another violent regime change in another oil-producing nation.