Henry Allan & Bryan Dyne

Earlier this year, NASA announced plans to build a Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway, which is slated to be humanity’s tenth space station and the first that will orbit the Moon. The Gateway is projected to be operational by the mid-2020s, with the first initial component of the outpost ready to launch in 2022. Congress has already provided $504 million for the initial planning and design of the space station and the project, if it goes forward, is estimated to cost $3 billion a year.

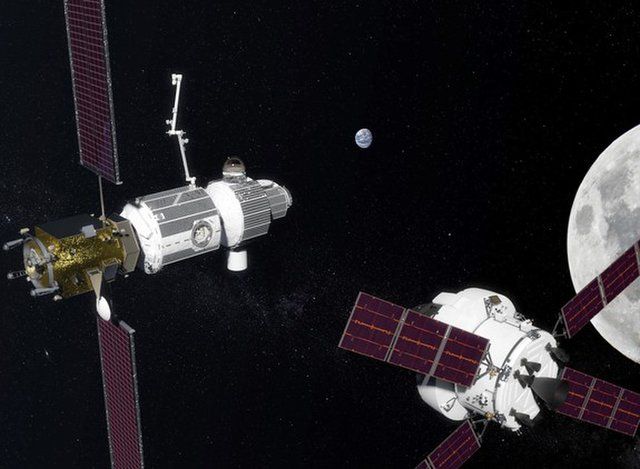

NASA’s planned Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway outpost (on the left), being approached by an Orion spacecraft as envisioned by an artist. Credit: NASA

NASA’s planned Lunar Orbital Platform-Gateway outpost (on the left), being approached by an Orion spacecraft as envisioned by an artist. Credit: NASA

NASA is promoting the Gateway as a lunar-orbiting station with scientific instruments attached externally as well as internally in order to conduct scientific experiments, control lunar rovers, or even act as a jumping off point for further ventures into space, including possible launches towards deep space.

“I envision different partners, both international and commercial, contributing to the gateway and using it in a variety of ways with a system that can move to different orbits to enable a variety of missions,” said William Gerstenmaier, associate administrator for Human Exploration and Operations at NASA Headquarters in Washington, earlier this year. “The gateway could move to support robotic or partner missions to the surface of the moon, or to a high lunar orbit to support missions departing from the gateway to other destinations in the solar system.”

Whatever its potential achievements, however, the development of the Gateway cannot be seen outside the context of the plan to create a “Space Force” as the sixth branch of the US military and the growing militarization of space in general.

When US President Donald Trump announced his intent to form the “Space Force” in June, he made it clear that the move was part of the war plans directed against Russia and China. “Our destiny beyond the Earth is not only a matter of national identity but a matter of national security,” Trump declared, adding that the United States should not have “China and Russia and other countries leading us.” He further emphasized, “It is not enough to merely have an American presence in space; we must have American dominance in space.”

House Space Subcommittee Chairman Brian Babin, a Texas Republican, echoed the national-chauvinist line of Trump, declaring, “Under the president’s leadership, we are now on the verge of a new generation of American greatness and leadership in space—leading us to once again launch American astronauts on American rockets from American soil.”

The Gateway would inevitably be a part of these efforts. A US space station orbiting the Moon immediately raises the possibility of policing of the space between Earth and the Moon, whether by manned or unmanned vehicles. These in turn would need a broader support network of spy satellites and other infrastructure necessary for such an undertaking, including space-based weapons.

It would no doubt also be used as an attempt to counter the influence of China, which is currently planning on building its own base on the surface of the Moon. It is not far-fetched to consider a “freedom of navigation” provocation, like those conducted repeatedly by the US military in the South China Sea, carried out against Chinese vessels in space. The Gateway might also be used as the pretext for attacking a craft that simply went too close to the station, violating its “territorial waters,” so to speak. Any of these could be used to start a war.

One view of the International Space Station. Credit: NASA

One view of the International Space Station. Credit: NASA

Such moves in the direction of new wars of aggression came into sharp focus when Trump announced the unilateral US withdrawal from the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces (INF) treaty with Russia, which prohibited Washington and Moscow from developing short- and medium-range missiles capable of carrying nuclear warheads. The withdrawal will set the stage for a further development of the US nuclear arsenal. It also poses the possibility of placing strategic weapons in space, perhaps even as part of the proposed space station.

The Gateway has also drawn criticism from scientists and astronauts who oppose the project as a drain on the already limited resources for space exploration. While the total cost of the Gateway is not fully worked out, it is already known that it will take twenty launches from currently available rockets to get the planned modules for the station to the Moon. This would eliminate twenty launches that could otherwise be dedicated to different unmanned interplanetary missions. While this could be reduced to as little as four if the Gateway was built with either NASA’s Space Launch System or SpaceX’s Super Heavy Starship, neither of those rocket designs have yet to be built.

Opponents of the Gateway have also pointed out that, unlike the currently operational International Space Station (ISS), because there are no agreements to share any benefits that might be gained from the Gateway, there are no cost-sharing agreements for the station’s operation. If US unilateralism on trade is an example of what will be demanded in space, then other nations will probably stick to the ISS or even begin developing their own, similar projects, with the same inherent risks—the danger of disaster in space and war on Earth.

It is also not clear that the Gateway would actually be a “stepping stone” to missions elsewhere in the Solar System. To arrive at the station, a spacecraft would have to enter orbit around the Moon, which costs fuel. As of now, a trip to the surface of the Moon that first stopped at the Gateway would require thirty percent more fuel. A trip to an asteroid, Mars or elsewhere faces similar problems.

No comments:

Post a Comment