Patrick Martin

Poor Americans are nearly twice as likely to die before they reach old age as rich Americans. That is the grim conclusion of a study released this week by the Government Accountability Office (GAO), the investigative arm of Congress, on the impact of widening income and wealth disparities in the United States.

The study is based on extensive health and retirement surveys conducted by the Social Security Administration in 1992 and 2014. It examines a subset of the population, those between 51 and 61 years old in 1992, breaking this age group into five quintiles.

A homeless man moves his belongings from a street behind Los Angeles City Hall as crews prepared to clean the area Monday, July 1, 2019. (AP Photo/Richard Vogel)

A homeless man moves his belongings from a street behind Los Angeles City Hall as crews prepared to clean the area Monday, July 1, 2019. (AP Photo/Richard Vogel)

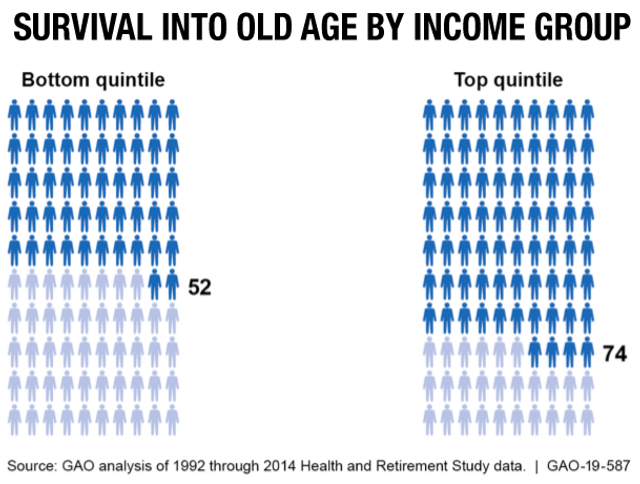

As the accompanying chart shows, the GAO found that nearly half of those (48 percent) in the poorest quintile died before 2014, when they would have been between 73 and 83 years old. Of the wealthiest quintile, only a quarter (26 percent) died.

The connection between income and death rates was stark and irrefutable: from quintile to quintile, as income declines, death rates rise. The second-poorest fifth of the age group under study had the second-worst death rate, with 42 percent dead by 2014. The figures for the middle fifth and the second-highest fifth were 37 percent dead and 31 percent dead, respectively.

And while the poor have always gone to the grave earlier than the rich, the relative disparity is now worsening. According to several recent studies, the poorest 40 percent of women have lower life expectancies than their mothers, despite all the gains made by medical science over the past generation.

These figures provide insight into the staggering long-term human cost of poverty and inequality. The report says, in dispassionate, bureaucratic language, “GAO’s analysis … shows that differences in income, wealth, and demographic characteristics were associated with disparities in longevity.” Translated into plain language: poverty and inequality kill.

Other statistics reported this week give further indications of the deepening social crisis in America. The GAO report itself found that from 1989 to 2018, the labor force participation rate for those aged 55 or older rose from 30 percent to 40 percent, an increase of one-third. This shows the impact of stagnant incomes and the virtual disappearance of traditional pension plans. Older workers were forced to work longer and postpone retirement because they did not have enough money to live on.

A Census Bureau report issued Tuesday found a small drop in the poverty rate in 2018, but other social indicators were not so favorable. The total number of people in the US living in poverty remained appallingly high, at 38 million.

Median household income was $63,200, essentially unchanged from 2018. On a longer historical timeline, the Census report found that there has been virtually no increase in real wages for the past 20 years, since 1999, as wage gains have been wiped out by the rising cost of living.

The chart shows the survival rate for the poorest fifth and the wealthiest fifth of Americans aged 51 to 61 in 1992. By 2014, 48 percent of the poorest group were dead, compared to only 26 percent of the richest group.

The chart shows the survival rate for the poorest fifth and the wealthiest fifth of Americans aged 51 to 61 in 1992. By 2014, 48 percent of the poorest group were dead, compared to only 26 percent of the richest group.

The number of Americans without health insurance rose substantially in 2018, for the first time since the passage of Obamacare in 2010, from 25.6 million to 27.9 million, mainly because of the reduction in the number of people covered by Medicaid and the Children’s Health Insurance Program (CHIP). Two policy changes by the Trump administration contributed to this decline: promoting new state regulations that restrict Medicaid eligibility, and threatening immigrants who apply for Medicaid or CHIP with being denied green cards in the future on the grounds that they have become “public charges.”

The Census report also confirmed the devastating dimensions of economic inequality in America. While the bottom fifth of households, those with annual incomes up to $25,600, accounted for only 3.1 percent of all household income, the top fifth, with annual incomes over $130,000, accounted for 52 percent, more than half. The top 5 percent, with incomes above $248,700, took in 23.1 percent of the total.

Rising inequality, persistent poverty, declining life expectancy for the mass of working people, the vanishing dream of a comfortable retirement: this is the reality that Trump hails as an America made “great” again. Nor do the Democrats—who controlled the White House for more than half the period in question—have any alternative. The two parties in Washington are rival factions within the same ruling elite, and they both defend American capitalism, the underlying cause of all these social evils.

The GAO report was not actually commissioned by Congress to expose the connection between poverty and premature death. On the contrary, its purpose was to examine the impact of changes in life expectancy on Social Security and Medicare so as to assist congressional efforts, supported by both parties, to cut spending on these “entitlement” programs long-term.

The authors of the report are quite conscious that their findings could be embarrassing to their congressional masters. They hasten to declare that they have found only a “statistical association” between poverty and higher death rates, adding that “we cannot determine from our analysis the extent to which income or wealth causes differences in longevity” [Emphasis added].

The report goes on to warn that despite lower life expectancy for the poor, “Taken all together, individuals may live a long time, even individuals with factors associated with lower longevity, such as low income or education. Those with fewer resources in retirement who live a long time may have to rely primarily on Social Security or safety net programs.” Translated into plain English: plans to eliminate these programs could run into widespread opposition, as they are increasingly the lifeline on which millions depend.

These fundamental social contradictions are the backdrop against which the working class is moving into historic struggles. Any major industrial action—such as a strike by the 155,000 workers at General Motors, Ford and Fiat Chrysler—can be the signal for the eruption of class conflict on a scale not seen in America since the 1930s.

American capitalism has been heaping up the raw material for such a political explosion for decades. Living standards for the working class have stagnated for more than four decades, with tens of millions in poverty in the richest country in the world, and more than a million homeless. The youth toiling in low-wage jobs are the first generation of American workers to live worse than their parents and grandparents. And these older generations, as the GAO report demonstrates, are finding it harder and harder to survive.

The decisive question is for working people to free themselves from the old organizations that have been used by the ruling elite to block any struggle against the profit system. This means breaking with the trade unions, run by corrupt stooges of the corporate bosses, and building rank-and-file committees democratically controlled by the workers themselves. And it means breaking from the nationalist perspective peddled by the trade unions, which seek to pit American workers against their class brothers and sisters around the world.

Capitalism is a global system, and it is impossible to fight the capitalists effectively in any country without the united efforts of the international working class. To carry out this struggle, the working class needs its own party, organized on an international basis and fighting for socialism in every country.

No comments:

Post a Comment