Hiram Lee

This is the second of a series of articles on the recent Berlin international film festival, the Berlinale, held February 5-15, 2015. The first part was posted February 19 .

Director Marcel Ophüls (born 1927 in Frankfurt, Germany) has devoted much of his career to an examination of the crimes committed during the Second World War and the fate of those who either collaborated with the Nazis or who opposed them.

The son of filmmaker Max Ophüls, he remains best known for his 1969 filmThe Sorrow and the Pity, which documented life under the collaborationist Vichy regime in France. He won the Academy Award for Best Documentary Feature in 1988 for what is perhaps his best film, Hotel Terminus: The Life and Times of Klaus Barbie about the infamous Nazi torturer’s escape to Bolivia with the help of US intelligence.

This year’s Berlin Film Festival exhibited the world premiere of a newly restored version of Ophüls’ 1976 documentary Memory of Justice. Prior to the screening, Ophüls was also presented with the Berlinale Kamera award, given to artists who “have made a unique contribution to film and to whom the festival feels especially close.”

Like nearly all of Ophüls’ films, Memory of Justice comes with a long running time, approaching five hours in this case. It covers a wide range of subjects including the Nuremberg Trials, the bombing of Dresden by the US military, US war crimes in Vietnam and the brutal methods employed by French colonial rule in Algeria.

There is much in the film that is valuable. Ophüls’ serious approach to historical questions, and in particular his investigations into the foundations on which postwar society was built, have real significance for contemporary audiences. Given the campaign of historical falsification currently underway in Germany aimed at relativizing the crimes of the Nazis, the screening of the film in Berlin was a significant event.

Nazis on trial in Nuremberg

Nazis on trial in Nuremberg

The first part of Memory of Justice centers on the Nuremberg Trials and features footage of the sessions. Retired Brigadier General Telford Taylor, chief counsel for the prosecution during most of the trials, is interviewed extensively, as are defendants Albert Speer and Karl Dönitz, both convicted of war crimes.

Dönitz, the naval commander who briefly succeeded Hitler as head of state following his suicide, remains unrepentant and provides some of the more outrageous commentary in the film. Speer, architect and Minister of Armaments and War Production for the Third Reich, who had already completed a 20-year prison term at the time the film was made, was by this time largely “rehabilitated.” In expressing regrets about his role in the Nazi regime, however, Speer was never as forthcoming as he would have liked viewers to believe.

Daniel Ellsberg in Memory of Justice

Daniel Ellsberg in Memory of Justice

The second part of the film takes up Vietnam and Algeria, and exposes acts that violate the precedents established in Nuremberg. This section features extended interviews with whistleblower Daniel Ellsberg, whose leaking of the Pentagon Papers exposed the war plans of the US government, and Henri Alleg, whose book La Question described his torture at the hands of the French armed forces in Algeria.

There is a striking moment when Ophüls confronts Edgar Faure of the Radical Party in France, then serving as president of the National Assembly. Faure had earlier functioned as French counsel for the prosecution during the Nuremberg Trials, but dismisses Ophüls’ questions about the methods used by France in Algeria, asserting that it is unfair to compare the actions of France, which had slowly built up colonies over time, to that of an invading war power such as the Nazis.

While he is adept at cross-examining many of his interview subjects, Ophüls is at his strongest as a filmmaker when he allows groups of ordinary people to talk amongst themselves, and argue over differing impressions of historical events and their implications. One is allowed a glimpse into some of the attitudes of the time and the often frustrated search for answers.

In another section of the film, a theater recounts to his fellow performers how a denazification officer once asked him, “Why didn’t you stand on stage and denounce the Nazis?” “They would have hanged us the next day!” he exclaims. Among the more significant sections of the film is the sequence concerning those who made fortunes collaborating with the Nazis and who continued to rake in massive amounts of money after the war.

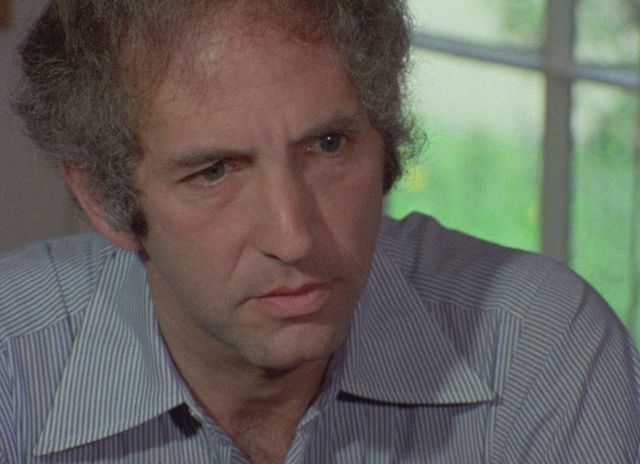

Telford Taylor in Memory of Justice

Telford Taylor in Memory of Justice

In particular, Taylor laments that industrialist Friedrich Flick, who profited from slave labor in the concentration camps, was granted an early release from his already minimal seven-year prison sentence.

Another commentator notes that SS Colonel Kurt Becher, who had been appointed commissar of all German concentration camps just prior to the end of the war, was now a big industrialist living in Bremen.

In fact, both convicted war criminals could be counted among the richest men in West Germany by the 1970s. Flick, in fact, was one of the wealthiest individuals in the world at the time of his death in 1972. While Ophüls exposes the hypocrisy of all the post-Nuremberg justifications offered for crimes in Vietnam and Algeria, and provides some sense of the social roots of fascism in Germany, he stops short of the more in-depth analysis required to truly understand the crimes documented in his work.

Ophüls may not agree with musician Yehudi Menuhin who declares in an interview conducted early in the film: “I go on the assumption that everyone is guilty.” But when Ophüls asks the mother of Mike Ransom, an American soldier killed in Vietnam, who wonders aloud what the Second World War really accomplished, “What was the alternative? Allowing hate to take over?” one suspects the director has accepted too many of the official stories about the Second World War.

In the end, one is left with something of an enormous tapestry, in which some of the threads do not hold together as well as they should, but in which others are richly stitched together. Ophüls has not told the whole story, but he has contributed much to our knowledge of some of the most barbarous crimes committed by imperialism in the last century.

Other documentaries

Along with Iraqi Odyssey , which we reviewed in our coverage of last year’s Toronto International Film Festival, one of the more significant films shown at the Berlinale was Tell Spring Not to Come This Year. Directed by Saeed Taji Farouky and Michael McEvoy, it documents a year in the life of soldiers from the Afghan National Army in the Helmand province following the withdrawal of NATO troops.

Most of the soldiers are terribly poor and have joined the army for that reason, though one complains he hasn’t received his salary in nine months. The film is thoughtfully made, with the directors able to capture a number of little moments—perhaps just a look, or a comment made to no one in particular—that often speak volumes.

Sequences in which the soldiers are deployed to confront local villagers are chilling. One soldier with his face covered by a mask tells a group of local police that if they don’t find out who has been shooting at their army base, the soldiers will “come back here and kill all ten of you.” They go on patrols, kicking down the doors to private homes and take their prisoners away in blindfolds. An opium farmer protests against their harassment: “If the government paid a good price for wheat, then everybody would grow wheat!”

Their role is to intimidate and subjugate the population. One is left asking: in what methods were these soldiers trained by NATO?

Getting to the heart of the matter, one soldier explains: “Everybody came to Afghanistan for their own personal gain. I live in a village on a hill. One day two foreigners came and said, ‘That’s our hill.’ They wanted what was under it.”

Kurt Cobain

Kurt Cobain

Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck and Fassbinder: To Love without Demandsdeal with the lives of Nirvana singer Kurt Cobain and German filmmaker Rainer Werner Fassbinder, respectively, both of whom died at an early age.

Fassbinder was responsible for some of the better films of the 1970s, including Ali: Fear Eats the Soul (1974), Fox and His Friends (1975) andMother Kuster ’ s Trip to Heaven (1975). Director Christian Braad Thomsen, who knew Fassbinder personally, has given us a psychological portrait of sorts, demonstrating Fassbinder’s apparent capacity for jealousy and extreme selfishness. There are tell-all interviews with Fassbinder’s frequent collaborators Irm Hermann and Harry Baer. Fassbinder, we are told, came to behave like the child he never had. It is another contribution to the depiction of the iconic filmmaker as a “bad boy” of cinema.

Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Rainer Werner Fassbinder

As to what conditions in postwar Germany, the period of the “Economic Miracle” and the radical movements of the 1960s and 1970s contributed to Fassbinder’s personality and the direction of his work, including its strengths and weakness, Thomsen never really bothers to ask.

With only the material shown to us in Thomsen’s documentary, it would be difficult to understand why Fassbinder remains a figure worth our attention today.

Kurt Cobain: Montage of Heck also places its subject, the Nirvana front man, on the analyst’s couch. The film focuses on a difficult home life, Cobain’s addiction to heroin and his often rocky relationship with his wife, singer Courtney Love.

Excerpts from Cobain’s journal entries, in which he rails against hypocrisy, the Reagan administration and everything he found phony about official life, provide at least some sense of what was on the troubled artist’s mind much of the time. The anger and disaffection (and much of the pessimism) of the generation that came of age in the 1980s and 1990s found expression in his music.

Early in the film, Cobain’s mother describes the town of Aberdeen, Washington, prior to Cobain’s birth in 1967, as a boomtown in which “even if you didn’t have much, you had enough.” Later, Cobain himself describes Aberdeen as “an isolated wasteland.”

Through what processes did this all-too familiar transformation take place and what was its impact on young people living through it? This is the question the film avoids, and the missing piece in all the biographies about the singer that have appeared over the years.