Fred Mazelis

At the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, April 3 through September 7, 2015

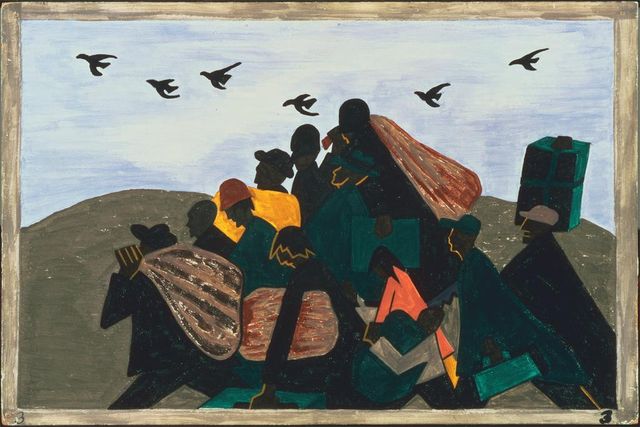

The current exhibition of the American painter Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City brings together the 60 small works depicting the mass migration of African Americans from the rural US South to the industrial North, and it is noteworthy on that account alone.

The show is doubly impressive, however, for its juxtaposition of Lawrence’s famous series with other painting, photography, writing, music and documentary records of this period. The fuller historical context provides a moving and thought-provoking experience, one that sheds some light on the entire social, political and cultural history of the past century.

In every town Negroes were leaving by the hundreds to go North and enter into Northern industry.

In every town Negroes were leaving by the hundreds to go North and enter into Northern industry.

The demographic shift depicted by Lawrence (1917-2000) is generally considered to have begun in 1915. By the time Lawrence completed his series of paintings, the black population of New York City, for instance, had quintupled in three decades, from 92,000 in 1910 to 458,000 in 1940. Between 1940 and 1970 this total would increase by nearly another four-fold, to almost 1.7 million.

In major Northern industrial centers like Chicago, Pittsburgh, Detroit and Philadelphia the pattern was the same. By the time the net exodus of African Americans from the states of the former Confederacy had ended, about 1970, around 6 million people had come north. This played an important role in the development of the American working class and transformed nearly every aspect of American life.

Fueling this massive internal movement was the desire to escape rigid Jim Crow segregation, a system of organized oppression and often of murderous violence. The migration could not have taken place, however, without the crucial social and economic changes taking place in the North—the growth of the urban centers and the development of basic industry, which opened up the possibility of jobs, improved living conditions and a better future for the African American workers from the South.

Originally entitled “The Migration of the Negro” upon its completion in 1941, when the artist was only 23 years old, the 60 paintings, along with the captions that were an integral part of the narrative, were equally divided between MOMA in New York and the Philips Collection in Washington DC. In 1993, about six years before he died, Lawrence slightly modified the captions, and the work was renamed “The Migration Series.” The complete set of paintings, in tempera on hardboard, has only occasionally been reunited for special exhibitions. The current show at MOMA is called “One-Way Ticket: Jacob Lawrence’s Migration Series and Other Visions of the Great Movement North.”

Lawrence had never been to the US South until shortly after he completed these paintings, but he was nevertheless deeply affected by the “great migration.” He was born in Atlantic City, New Jersey, to parents who had come from the South. The family moved to New York in 1930, and Lawrence came of age in the depths of the Great Depression and amidst the growth of radical ideas among workers, young people and intellectuals.

Lawrence was shaped in large part by the Harlem Renaissance, as the movement that emerged in the 1920s among African American artists, writers and intellectuals came to be known. He counted among his friends such figures as Ralph Ellison, Langston Hughes and Richard Wright, who gave written expression to the growing anger and opposition to racism and discrimination, in both North and South, and each of whom, for at least a brief period, joined or sympathized with the American Communist Party.

While there is no indication that Lawrence, some years younger than these writers, went as far in his political involvement, there is no doubt that he was formed by this period and atmosphere. He saw his artwork as serving a social and political purpose. Like other young artists, he obtained regular work through the Works Progress Administration, the federal program established in the New Deal years as part of the reforms of the Franklin D. Roosevelt administration. A precocious and talented artist, Lawrence had already attracted attention prior to the exhibit of the “The Migration of the Negro” in 1941.

Before he set to work on the migration paintings, Lawrence carefully researched the period, working for months at the Harlem branch of the New York Public Library (today the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture). He later stressed the immediacy of the question of the migration during these years, explaining, “people would speak of these things on the street.” He also developed his ideas and methods by working on narrative cycles of paintings dealing with Haitian revolutionary Toussaint L’Ouverture and anti-slavery leaders Harriet Tubman and Frederick Douglass.

In the current show the 60 paintings are presented in a spacious rectangular gallery, with a dozen iPads, on a long table in the center of the room, for more detailed study of the individual panels as they follow a roughly chronological path.

The experience of seeing the paintings together is a compelling one, and it should ideally be viewed as a unit at all times. One is struck by the artistic and historical coherence of the work.

Lawrence worked on the series systematically, with a relatively small range of colors. He began with black, applying the paint to all of the panels in turn. He then proceeded to progressively lighter colors until the series was finished. During this whole process he worked in collaboration with his fellow painter Gwendolyn Knight, whom he had met several years earlier, and who became his wife in 1941.

There is a powerful simplicity to the work. The relative sameness of the figures, and the fact that features are not clearly delineated, calls attention to the universality of these individuals and the story they tell. Individual detail is sacrificed, but something else is gained. The understatement is effective for this narrative. Lawrence’s portrayal of humanity has a dignity but not a false heroism.

The combination of colors, including yellows, browns, greens and reds, is also successful. There is life here, although it is a somber story. Most of the migrants traveled by railway to the urban centers of the north, where they found employment and sometimes improved living conditions, but also new challenges, including other forms of discrimination and exploitation.

Lawrence combined his social commitment with a thorough grounding in art history and technique. He spent many hours at the Metropolitan Museum of Art studying the work of Renaissance masters. He also looked to such painters as Stuart Davis and Charles Sheeler, and the Migration Series is a thoroughly modernist work, while at the same time, as one curator expressed it, “history writing in visual form.”

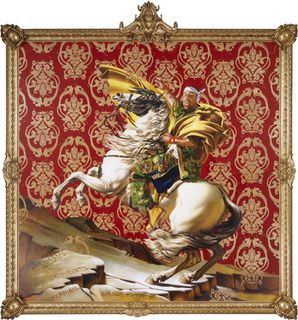

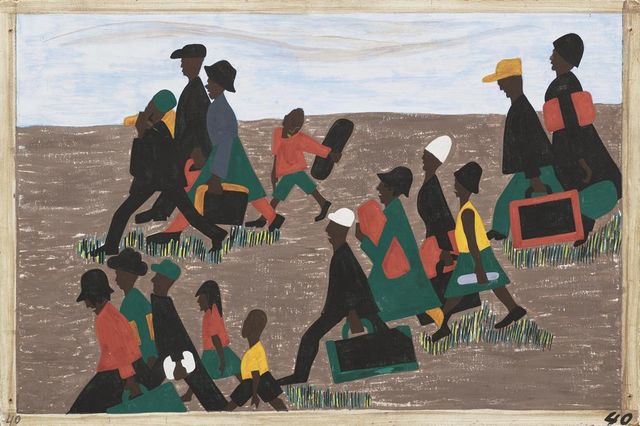

The influence of modernism can be seen in one of the early panels in the show, showing the migrants en route. A small crowd, taking a triangular shape, is mirrored by the image of migratory birds in the sky above. “In every town Negroes were leaving by the hundreds to go North and enter into Northern industry.”

They were very poor.

They were very poor.

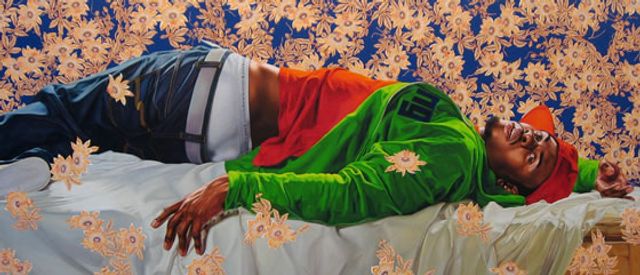

The artist portrays the poverty and dignity of his subjects in a panel entitled, “They were very poor.” Two figures sit at a table, their heads bowed in prayer, and two bowls and a pot on the wall nearby testify to their bare subsistence.

Another early panel brings out the working of the Southern “justice” system. Two defendants stand with their backs to the viewer and a scowling judge towers above, no doubt handing down a draconian sentence.

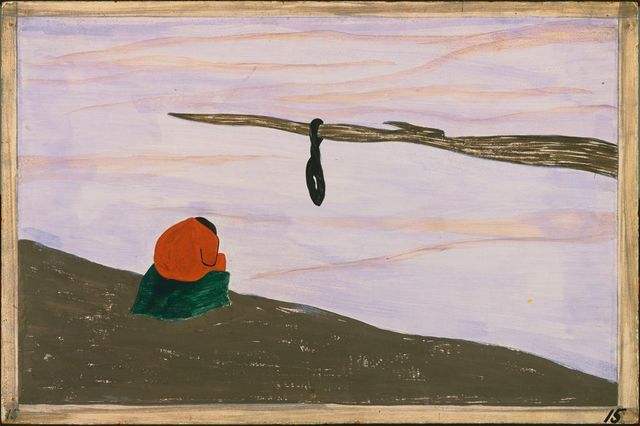

Another cause was lynching. It was found that where there had been a lynching, the people who were reluctant to leave at first left immediately after this.

Another cause was lynching. It was found that where there had been a lynching, the people who were reluctant to leave at first left immediately after this.

One of the most powerfully understated images in the show is that of a lynching, depicted only by a noose, without a body. A grieving figure nearby reflects the permanent loss inflicted by racist violence.

Another painting suggests the mass character of the migration. Three men are pictured talking near a fence, and the caption explains, “people all over the South began to discuss the great movement.”

The labor agent also recruited laborers to break strikes which were occurring in the North.

The labor agent also recruited laborers to break strikes which were occurring in the North.

As Lawrence moves on to depict the challenges facing the migrants in the North, he does not shy away from other big issues. One panel shows a “labor agent” who “recruited laborers to break strikes which were occurring in the North.”

The migrants arrived in great numbers.

The migrants arrived in great numbers.

The ongoing character of the migration is brought out by the regular appearance of panels portraying working people in motion, accompanied by captions with a similar refrain: “The migrants arrived in great numbers”; “And the migrants kept coming.”

Other paintings show the poor housing migrants faced in the North, the industry (particularly the steel mills in Pittsburgh and Chicago) in which they found employment, and an especially important panel dealing with Northern “race riots.” The caption explains that these were “very numerous…because of the antagonism that was caused between the Negro and white workers.”

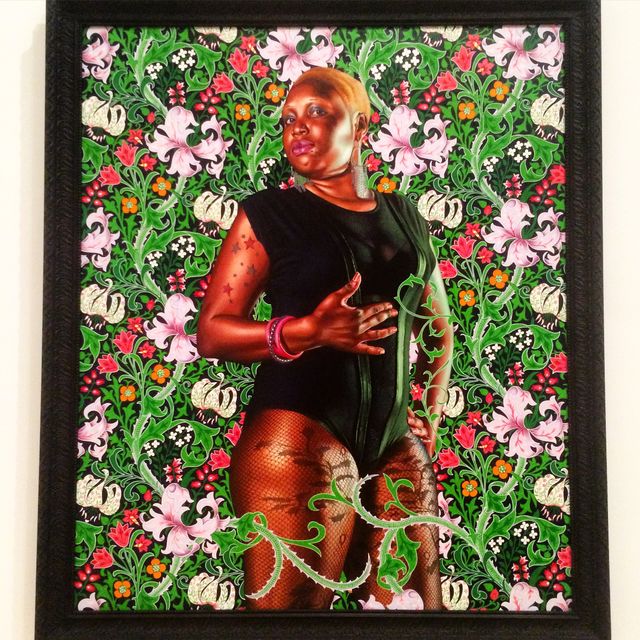

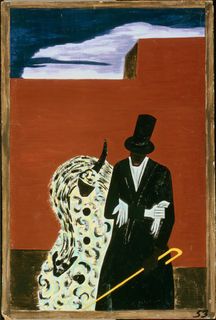

One panel suggests the class divisions and stratification within the African American population. An upper middle class couple is depicted, and the caption reads, “The Negroes who had been North for quite some time met their fellowmen with disgust and aloofness.”

The Negroes who had been North for quite some time met their fellowmen with disgust and aloofness.

The Negroes who had been North for quite some time met their fellowmen with disgust and aloofness.

As already noted, the other rooms in this exhibition add immensely to the experience, and any one of them could be the subject of another review. The accompanying work includes other paintings by Lawrence as well as by Lawrence’s teacher Charles Alston and other African American painters, including William H. Johnson, Romare Bearden and Charles White.

Attention is also devoted to photography of the period, focusing in part on images from the Depression and the following decade, including important work by Ben Shahn, Dorothea Lange, Helen Levitt, Aaron Siskind, Jack Delano and others. Here the subjects include white workers and immigrants, bringing out some of the broader issues facing the working class during these years.

Included is Margaret Bourke-White’s iconic photograph from Life magazine, “‘The American Way’ and the Flood of ’37.” A line of impoverished African Americans seeks food and clothing in Louisville, Kentucky following the devastating flood, while a huge billboard behind them declares, “There’s No Way Like the American Way.” The show also includes some famous work by Morgan and Marvin Smith, twins who were based in Harlem and worked as a photographic team, including the Smiths’ photos of Harlem residents listening to street corner speakers and other scenes of everyday life.

Two historic film clips are also on view: one of Marian Anderson at the Lincoln Memorial, in the famous 1939 appearance after the Daughters of the American Revolution prevented her from appearing at Constitution Hall; and another of Billie Holiday singing “Strange Fruit,” the famous song about lynching she first introduced in 1939.

Finally, this Migration Series exhibition includes portraits and audio excerpts from musical figures associated with the Harlem Renaissance or the Great Migration: Louis Armstrong, Duke Ellington, Paul Robeson, Huddie Ledbetter (“Leadbelly”), Bessie Smith, Fats Waller, Josh White, Mahalia Jackson and the classical composer William Grant Still.

The Migration Series illustrates some of the strengths as well as the limitations of the Harlem Renaissance. It was not really a movement with a coherent outlook, but rather reflected the emergence of an African American artistic intelligentsia with a variety of outlooks and ideas.

Some of the figures associated with the Harlem Renaissance saw their role in purely or primarily racial terms. Others were attracted to Marxism, at least to some extent, and recognized the role of racism as a tool to divide the working class. Lawrence was apparently inclined in this direction.

But Lawrence emerged in the heyday of the Popular Front period, in which the Stalinist parties worldwide, including the American CP, subordinated the working class to the needs of the Soviet bureaucracy for an alliance with the liberal sections of the bourgeoisie. Stalinism played a destructive role not only in relation to adherents of the CP but also in broader left-wing circles, including figures such as Lawrence.

It is worth noting that Lawrence, although he continued to paint and produce interesting work for many decades, is best known for the work he completed as a young man. The artistic difficulties he confronted were essentially the same as those faced by a generation of artists after the Second World War. Figurative painters were out of fashion, as were those who concerned themselves with social and historical themes. Later, Lawrence also rejected the “political” art associated with nationalism and identity politics.

These problems were bound up, in a complex fashion, with the history of the 20th century, including the protracted degeneration of the Russian Revolution and the crisis of perspective facing the international working class. In any case, Lawrence’s work on the Migration Series, along with the other achievements included in the current exhibit of this work, raises vital issues concerning the current crisis of culture more generally.

There is also the important historical question of the Great Migration itself. The exhibit somewhat misleadingly states that the population shift ended in 1970 because the achievements of the civil rights struggle meant that African Americans could now enjoy equal rights in the South. This conception goes hand in hand with the approach that sees the main element fueling the migration as racism and discrimination.

In fact, a change took place beginning in the 1970s primarily because of the deepening economic crisis and deindustrialization in the urban centers to which African Americans had flocked. As decent-paying jobs dried up there was no longer the impulse driving migration, and in recent decades there has in fact been a slight “reverse migration,” including retired as well as some younger workers attracted in certain cases by a lower cost of living in the South. The Great Migration and all the subsequent history can only be understood in class terms.

The population shift that is the subject of Jacob Lawrence’s gripping work transformed the US. It anticipated the civil rights struggles centered in the South as well as the urban rebellions in the northern cities of the 1960s. It led to the growth of the industrial working class and, between the 1930s and 1960s, common struggles of black and white workers for better living standards and basic rights.

The end of the internal migration, however, coincided with the end of the period of partial and limited social reform under American capitalism, exemplified first by the New Deal and later by the gains made by the working class as well as the civil rights reforms and the “War on Poverty.”

Today a deep crisis faces the entire working class—a crisis not only of unemployment and poverty, but also of police violence, attacks on democratic rights and the growing threat of world war. Where are the artistic voices who will represent this new situation?

Artists with Lawrence’s sincerity and aesthetic sense don’t come along every day. The influence of selfish identity politics, including a debilitating racialist approach to every aspect of life, has made it far more difficult for artists in recent decades to find their way to the most earthshaking questions. Objective events above all, including a mass movement of opposition to the status quo, will bring about a change in mood and compel a new generation of artists to address themselves, applying all sorts of novel techniques and methods, to the circumstances facing millions. (See the Lawrence exhibit.)