Serge Jordan

A year after ISIS captured Mosul, the jihadist group controls about half of Syria and a third of Iraq – more territory than ever before

A year after the self-proclaimed “Islamic State of Iraq and Syria” (ISIS) captured Mosul and declared its “caliphate”, it now controls about half of Syria and a third of Iraq - more territory than ever before. The legacy of imperialism, with decades of divide-and-rule policies, power struggles, corporate plunder, support for brutal dictatorships, flirtations with jihadist forces and bloody military interventions, has left these two countries in ruins, reflected in a rapid descent into sectarian fragmentation.

Existing nation States, creations of colonialism, are being increasingly hollowed out, as the old map of the Middle East is redrawn with the blood of the masses. The old imperialist order, established after the collapse of the Ottoman Empire a hundred years ago, is being radically reshaped in a sectarian battleground that has engulfed much of the region. The advance of ISIS is merely symptomatic of this general process. The fight against this group—a common agenda that had supposedly united all nations over the last year--is faltering as the competing powers have failed to come up with any unified strategy.

On May 17, the Iraqi city of Ramadi fell into the hands of ISIS. The takeover of Ramadi, capital of Anbar, Iraq’s largest province, represented the biggest military victory for the Sunni fundamentalist group since the fall of Mosul a year ago. In a replay of the military debacle in Mosul, fleeing Iraqi elite units abandoned a vast amount of their U.S-supplied equipment to ISIS fighters.

Over 100,000 people have fled Ramadi in the past few weeks. Stranded in the desert, some of the displaced have died of heat and exhaustion. More people are predicted to flee as anti-ISIS forces are preparing for a bloody showdown to regain the city, raising the likelihood of a drawn-out battle with mass killings and destruction.

Sectarian fault lines are being pushed to new heights. ISIS has used its newly acquired position in Ramadi to threaten an attack on the shrine city of Karbala, seen by the Shia as one of their holiest sites. Many Sunnis displaced from Ramadi have been officially denied entry into Baghdad, because of fears that there could be ISIS infiltrators in their midst. Such overt scapegoating, coupled with a denial of assistance from central government authorities, might ironically cause desperate Sunni refugees to instead turn to ISIS for succour.

As violence spreads through Iraq, the International Organisation for Migration (IOM) has estimated that since the beginning of 2014, the number of displaced people in the country has reached a record figure of 2.8 million. Terrorist attacks against civilians are intensifying, and hundreds of people are killed in these murderous encounters every month.

Downplaying the disaster

Despite the attempts of US officials to downplay the fall of Ramadi, it indeed represents a big blow to Western imperialism’s campaign to “degrade and ultimately destroy” ISIS. American airplanes bombed ISIS positions around Ramadi 165 times over the month preceding its capture. This clearly made little difference. The assumption that the air strikes would at least curtail the momentum of the ISIS, if not outright defeat it, has been shattered.

In contrast to the US Army’s upbeat argument that coalition airstrikes had put ISIS on the back foot the last couple of months, this defeat also exposes the futility of the blood spilled by Washington’s warmongers, and the self-defeating results of their policies: during the post-2003 US invasion and occupation, the bloodiest battles were fought by the US army to capture Fallujah and Ramadi from Sunni insurgents. Both cities are now in the hands of ISIS – a decidedly more reactionary, murderous group than the ones fought by the US troops at that time.

Since Ramadi’s fall, Iraqi and American rulers have traded accusations over who is to blame for the defeat. Iranian officials made their stand clear, through the words of Iranian General Soleimani, who said that the US had so far “not done a damn thing” in the fight against ISIS. This is taking place against the backdrop of an increasing assertiveness of the Iranian regime on the Iraqi battlefield.

Shia militias

Reneging on its previous injunction, the Iraqi government has taken the explosive decision of deploying Shia militias in an attempt to retake Ramadi–a predominantly Sunni city in a predominantly Sunni province. Known as “Popular Mobilisation Units”, this umbrella organization of Shia militias, has at its core the Badr Corps, military wing of the Badr Organisation, a Shia party founded as a branch of the Iranian Revolutionary Guards in the 1980s.

Up to this point, Iraqi Prime Minister Haydar al-Abadi had ordered these Shia militias to stay out of Anbar province. Yet the latest decision was made necessary because of the ignominious collapse of the corrupt Iraqi Army, that was armed and trained at a cost of $25 billion by Washington, and assisted since last year by thousands of US trainers.

JournalistPatrick Cockburn, in one of his dispatches about the ISIS, estimates that now the Shia paramilitary forces in Iraq number between 100,000 and 120,000 men, while the regular army, that has suffered heavy losses due to fighting and desertions over the last 18 months, has only between 10,000 and 12,000 combat-ready soldiers. Hence, the government had run out of option.

Heightened sectarian tensions

Earlier campaigns launched by the Shia militia have been accompanied by sectarian reprisals against the Sunni population, often indiscriminately treated as de facto ISIS supporters. The Shia militias have played a leading role in the government’s effort to recapture the northern city of Tikrit, the home town of Saddam Hussein, from ISIS’ hands earlier this year. However, the city has remained largely a ghost town since then, with Sunni residents afraid to return.

After the city’s recapture, Shia militias engaged in widespread looting and mass executions, burning hundreds of homes, and forcing thousands of Sunnis to flee. Similar scenes have taken place in Saladin, Diyala, and other places where ISIS fighters have been driven out.

These Shia-perpetrated atrocities on the civilian population mirror those committed by ISIS, raising the spectre of a new general sectarian bloodbath in Iraq. “Our main concern is that the security forces will accuse us of supporting ISIS because we stayed in the city”, a Ramadi resident commented in a recent interview, pointing out the Sunnis’ widespread fears for their lives in ISIS-controlled territory.

These fears, coupled with past grievances and rejection of the years of persecution by Shia-dominated regime forces, are exploited by ISIS militants to secure a social base among the most alienated layers of the Sunni population, or, at the least, some form of tacit acceptance of their rule. This is helped by the perceived military collusion between the Shia militias, Iraqi government forces and the US-led anti-ISIS airstrike campaign.

Troops on the ground?

The US government has admitted that in the offensive to retake Ramadi, it would give close air support to all forces who are working under the control of the Iraqi government. The increasing dependence on Shia militias, politically aligned with the Iranian regime, is a testimony of the embarrassing dilemma facing Obama’s administration. These Shia forces involve groups such as Kitaeb Hezbollah, responsible for carrying out hundreds of attacks on US soldiers after the 2003 invasion, and still listed as a terrorist organization by the US government.

The tentative rapprochement with Iran has started generating tensions between US imperialism and the Gulf monarchies, opening fractures within the so-called “coalition of the willing”, as well as with the Israeli government – especially in the aftermath of the impending nuclear agreement with Iran, which already infuriated these traditional American allies in the region.

This situation is also exacerbating divisions within the US political establishment. The lack of real progress in the months-long air campaign against ISIS and the absence of reliable troops on the ground--a vacuum increasingly filled up by a competing Iranian presence-is heightening the debate in American ruling circles about US military involvement in Iraq, in the run-up to the 2016 presidential campaign.

Under pressure, Obama announced a plan this week for establishing a new military base in Anbar province, and for deploying 400 additional US trainers to help retake the city of Ramadi. British Prime Minister David Cameron followed suit, saying he would send up to 125 additional troops to train Iraqi forces. Later on, the Pentagon said it was looking at creating a “lily-pad” of sites that would re-establish a presence across Northern Iraq, in locations used by the US army when it occupied the country.

When Obama took office in 2008, he had campaigned to end the war in Iraq and keeping the U.S. out of new military conflicts. Hence his earlier insistence on “no boots on the ground”. But for months now, some US military leaders have been suggesting that they will need US troops on the ground to play a more active role. In Britain, Lord Dannatt, the former head of the army, called for a parliamentary debate on the dispatch of 5,000 British troops.

So far, such voices have remained in a minority. Obama and other western leaders have to deal with their own populations that have no real appetite for new military adventures in the Middle East, as past fiascos remain fresh in public memory. While the frantic media campaign displaying the savage violence of ISIS initially pushed a layer into thinking “something needs to be done” and supporting some form of military intervention, opinion polls indicate that this support has already waned. The developing quagmire is unlikely to boost the number of interventionist-enthusiasts among ordinary people.

That is why the US administration has tried to favour options that would keep its forces out of the firing line as much as possible. This has been done by sending new weaponry (such as anti-tank rockets) to the Iraqi government, and by promising to lif all constraints on Iraq’s access to weapons ---(though much of the earlier acquired arms and ammunition have ended up in the hands of ISIS.

A lot of noise is also heard about pushing the delivery of weapons and assistance to Sunni tribes that would be prepared to confront ISIS, in a new version of the “Awakening” movement ---where some Sunni tribes grew sick of al-Qaeda and cooperated militarily with the then US-backed Iraqi government in 2006-2007. But this only worked at the time because the whole operation was backed by 150,000 American troops, and was directed against al-Qaeda, a group which was much weaker than what ISIS has become today.

In these conditions, a “mission creep” scenario could develop. The recent enlargement of US training mission makes clear that a surge of US military presence in Iraq is not impossible. However, the result of such a scenario would take the ongoing catastrophe to new heights, as past experiences have amply demonstrated.

Kurdish resistance

Although ISIS has achieved prominent military victories, the situation remains very fluid, with a lot of ebbs and flows, and some episodes in the past few months have also highlighted ISIS’ inherent weaknesses. Most significant among the setbacks suffered by the ISIS, is the failure of the group to capture the Kurdish town of Kobanê despite an intense 134-day siege, and they had to eventually back off in the face of the relentless resistance put up by the predominantly Kurdish armed factions of the YPG (People’s Protection Units) and YPJ (Women’s Protection Units), who had established a territorial base in three cantons of northern Syria, now commonly referred to as Rojava. Since the beginning of May, the YPG/YPJ have wrested back more than 200 Kurdish and Christian towns in north-eastern Syria, as well as strategic mountains seized earlier by ISIS.

The resistance put up by the YPG and YPJ in Kobanê, and in and around Rojava, has shown that ISIS can be defeated. Unfortunately, this resistance relies essentially on the heroic actions of guerrilla units rather than on the democratic, mass mobilisation of the people themselves. Within its limits, it has shown that when anti-ISIS fighters are motivated by an agenda linking up armed defence with appeals for national liberation of oppressed communities and social change, noticeably encouraging women to take their place in the struggle and fight for their rights, getting sympathy among workers, poor peasants and young people, a difference can be made and the most ruthless reactionary groups can be put in check.

The victory of Kobanê’s resistance has shown, in a somewhat deformed fashion what would be possible on a large scale if a mass, non-sectarian, working people-led resistance was being put into play in the region. It highlights the fact that ultimately, ISIS military successes elsewhere have a lot to do with the lack of a serious contender capable of challenging it through rallying the mass of the population behind a broad-based program of radical transformation of society that many people in a region ravaged by poverty, war, sectarianism and state terror, are yearning for.

Yet the CWI has warned from the beginning about the fault lines in the strategy and methods of the leadership of the PYD (the political wing of the YPG/YPJ). The dangerous expectations of the PYD leadership to get political payback from Western imperialism, should be opposed by genuine socialists. “We want to build good relationships with the US”, commented one leader of the PYD, Sinam Mohamad, last April. The YPG is in close contact with the US-led coalition and sometimes asks for airstrikes targeting ISIS positions after its fighters locate them.

Beyond the western powers’ disregard for the Kurds’ deep-rooted aspirations for self-determination, if the initiative for the struggle against ISIS is left in the hands of imperialist powers, who are now collaborating with Shia death squads massacring Sunni civilians, the potential appeal of that struggle to a wider working class audience will be totally undermined, even more so among poor Sunnis, who constitute the pool which ISIS relies for support and fighters.

Furthermore, Kobanê has been totally wrecked by the bombing. The level of destruction of the city shatters any hope for a quick return to normal life for the local population. This is partly due to the carpet-bombing tactics of US military planes and their absolute lack of consideration for human lives and people’s habitations.

Kobanê in ruins

A matter of greater concern are several recent reports that point to attacks on Sunni Arab civilians perpetrated by YPG/YPJ fighters, and to the fact that thousands of Sunni Arab civilians in northern Syria would have fled their homes to avoid to be targeted in what has been described as an apparent “ethnic cleansing” campaign. While these instances have remained isolated and are certainly not widely endorsed by supporters of the “Kurdish Spring” in Rojava, they point at a very dangerous development threatening to destroy the progressive claims made by a movement that many workers and youth,in the region and beyond, looked at with inspiration.

ISIS’ advances in Syria

At present, northern Syria is the only area where ISIS seems to be losing substantial territory. Elsewhere in that country, ISIS has escalated its offensive, moving from consolidation by tightening its grip on territory under its control to gaining new ground.

A few days after the fall of Ramadi, the Syrian city of Palmyra was captured by ISIS troops. Mass executions by ISIS, including of children, was reported immediately afterwards. Important gas fields nearby were seized, depriving Assad’s regime of an important source of energy production and revenue. ISIS also demolished and destroyed the infamous Palmyra military prison, that served for decades as the dark heart of the Syrian regime’s system of brutal coercion and torture.

Palmyra is a strategic target: it houses military bases and an airport, as well as major crossroads linking the Syrian capital Damascus with territory to the east and west. It also helps ISIS in its objective of securing a stranglehold over the city of Deir Ezzor, the last area in the East where government troops are still holding out. A fresh offensive by ISIS is also underway in the northern province of Aleppo. If ISIS seizes the area, it would extend its territory along the Turkish border, amplifying its capacity to secure supplies and smuggle in foreign fighters.

Syria’s implosion

The civil war in Syria is dragging on to its fifth year, with no real end in sight, alongside regular UN-sponsored peace talks which have predictably achieved nothing.

Estimations of the death toll are approximate, but most accounts put the number at over 300,000. The war has created the desperate flight of millions of refugees into neighbouring Jordan, Turkey and Lebanon. About half of the Syrian population has been driven from their homes. Many parts of the country are hardly recognizable, the economy is in shambles, and this is accompanied by a breakdown of public services and an outbreak of epidemics. The World Health Organisation says 57% of Syria’s public hospitals have been damaged, while 4 out of 5 Syrian live in poverty. Indiscriminate attacks in civilian areas, from all sides, are on the rise. Chemical weapons are being deployed, and there is an escalation in the use of rape as a weapon of war, arbitrary executions, abductions, torture and the use of child soldiers.

The movement against Bashar al-Assad’s dictatorship in 2011 was inspired by the revolutionary uprisings in Tunisia and Egypt. But, because of the lack of a sufficiently strong, independent working class movement capable of challenging the violence and sectarian incitement by both Assad’s dictatorship and Sunni fundamentalists, the progressive, popular elements of the mass movement were pushed into the background, giving place to an increasingly multi-sided sectarian civil war tearing the country apart. This process was largely intensified by the intervention of competing outside powers fighting for regional influence.

Proxy war

Several close allies of the US in the anti-ISIS coalition have continuously funded violent jihadist groups in Syria. Despite their previous frictions, the regimes in Saudi Arabia, Turkey and Qatar have repaired relations and drawn closer together in the recent months, joining their efforts against Assad’s camp by arming and funding a coalition of hard-line Islamist rebel groups called “Jaish al-Fatah” (“the Army of Conquest”), dominated by al-Qaeda’s affiliate in Syria, Jabhat al-Nusra. This coalition has notably managed to capture the city of Idlib at the end of March, along with most of the Idlib province.

The transformation of the political landscape in Turkey following the country’s recent elections might bring into question the Turkish State’s new alliance with the Qatari and Saudi regimes, and its assistance to jihadists in Syria.

Turkish President Erdoğan visiting newly appointed Saudi King Salman

Nevertheless, this chapter shows again the complete mess that US imperialism has been drawn into, and the growing disunity developing within the formal coalition it has assembled against ISIS -with some of its allies teaming up to openly fuel the jihadi fire, considering the fight against Assad and the Shia axis as more important than the campaign against ISIS. The historic erosion of US hegemony in the region has left more space for regional powers to assert their own political agendas, and the clashing interests of all the actors involved has led to a Kafkaesque situation –with the US government engaged in a tightrope walk, not knowing where to stand.

As the US administration’s plan to arm and train a “moderate” rebel force has collapsed (according to Pentagon sources, only 90 rebels have taken part in this program so far), some Western analysts are trying to bridge the gap by echoing the propaganda from Turkey and the Gulf, by laundering the image of the supposedly more moderate jihadists of Al-Nusra, arguing that this organisation, despite its notorious record and an ideological project hardly any different from ISIS, can be a useful counterweight against both Assad’s regime and ISIS itself.

As Turkey, Saudi Arabia and Qatar have stepped up the coordination of their activities through such Al-Qaeda type proxies, the Iranian government has reportedly decided on its part to send 15,000 regular army troops into the country to support the Syrian regime’s forces. These escalating moves will aggravate the already charged sectarian tensions, that are not only carving up the country and dragging Syrian people into increasing horrors, but also ruining the future of the entire region with the threat of a wider military conflagration.

Assad losing ground

In the last few weeks and months, different factions of the armed opposition have won a string of battlefield victories against Assad’s forces; Iran’s recent decision has taken place in this particular context. For instance, the loss of a major military base in the Southern Daraa province on June 9, used by the regime as a Launchpad to attack and shell many towns and villages around the area, has exposed these weaknesses further. While Assad’s clan is still strong on the Western side, he has been hit hard by losses in the south, north and east of his country, not just to ISIS and al-Nusra, but also to other Sunni armed groups.

This flows from four years of relentless war of attrition that is eating away the pro-regime forces. Deaths or desertions have hit nearly half the regime’s soldiers, and an estimated one-third of Syrian Alawite males of military age have already died in the fighting. This has led to a growing difficulty to recruit new fighters among the local Alawite population.

These setbacks have compelled Assad to heavily rely upon fighters from his regional allies to compensate for the losses: Iranian Revolutionary Guard Corps, the Shia group Hezbollah from neighbouring Lebanon as well as volunteer Shia fighters and mercenaries brought from Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan and Yemen.

Assad’s military is running so short on manpower that Iran has reportedly been forcing Afghan immigrants to choose between prison and serving on the front lines in Syria. These immigrants originate from the Hazara refugee population, a Shia minority that are the poorest of the poor in Afghanistan, and are being used as cannon fodder in the Iranian regime’s war plans.

According to Lebanese military sources, the number of Hezbollah fighters in Syria has doubled since 2013. The group has enlarged its geographic sphere of military activity, and has de facto become the main group fighting beside the Syrian army, helping on several occasions to retake areas occupied by various Sunni groups. To sustain this momentum, Hezbollah has stepped up its recruitment activities within Lebanon, targeting not only Shias, but even other minorities, such as the Druze and Christian groups. This highlights the real and growing threat of a sectarian blowback of the conflict into Lebanon too.

Fractures at the top

The Assad regime’s defeats on the battlefield have opened up divisions within the Syrian government and the top echelons of power. While they do not automatically predict a downfall of Assad –he still controls the bulk of Syria’s most populous areas, up to 60% according to most estimates-- these defeats do indicate that his regime is at its most vulnerable position since the start of the mass revolt in 2011.

Alawite families are less and less willing to sacrifice their sons to keep Assad in power, there have been protests in predominantly Alawite areas to resist military conscription. The Syrian economy is also buckling under the costs of war, and the regime has been unable to maintain fuel and food subsidies, increasing popular anger in the areas under its control.

The Iranian economy has itself been crippled by sanctions and falling oil prices, raising questions as to how long it can inject billions of dollars to preserve Assad in power. These difficulties might result in more decisive moves by the Syrian regime to retract its forces to protect the capital city of Damascus, the coastal areas, the Western cities of Homs and Hama, and other areas seen as central to the regime’s survival.

A removal of Assad, either through some diplomatically negotiated deal through his foreign backers, or through a coup from within the regime itself, cannot be ruled out. The removal of Assad would probably preserve big parts of the repressive State machine in place, and would be no deterrent to the empowered Sunni jihadist groups and their regional backers; the war would continue to grind on, providing no real exit strategy for the Syrian population. While moves that stop the suffering of ordinary Syrians would be a welcome development, any arrangement from the top by foreign powers, with or without Assad, would be in the interests of these powers, leaving the Syrian masses drained, divided and suffering under the fist of a new bunch of profiteering gangsters.

Sectarian break-up

In both Iraq and Syria, sectarianism is at a feverish pitch, and because of their sectarian essence, none of the existing armed groups will be able to put these countries back together. The formal “national” armies of the Iraqi and Syrian states, retracted on their sectarian support base, are both rendered increasingly ineffective and relying on outside sectarian militias for back-up. This is symptomatic of the broader break-up at play, the previous nation states of Iraq and Syria de facto disintegrating and splitting into sectarian enclaves under the control of competing armed groups.

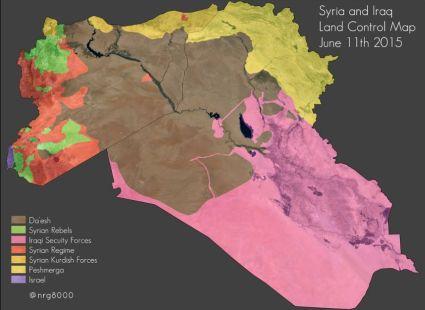

Map showing the division of territories in Iraq and Syria on June 11 (’Daesh’ is the Arab acronym for ISIS)

This is the product of long-standing divide-and-rule policies by imperialist powers and local rulers, who have systematically pit communities against each other for the sake of securing riches, power and privileges for themselves. The bloody imperialist invasion and occupation of Iraq in particular, has unleashed sectarianism to an unprecedented degree, which has been further nurtured by the neighbouring Syrian conflict. The monstrosity that is ISIS is a by-product of both wars.

“No strategy”

Since its bombings began last August, the US has spent more than $2.7 billion on the war against ISIS ($9 million a day). Despite the coalition having gone on more than 3,700 bombing runs in Iraq and Syria, killing many civilians in the process, this air warfare has failed to fundamentally alter the situation on the ground. Terrain might continue to regularly change hands in the future, but it would not be far-fetched to say that the US-led coalition is not winning this war against ISIS. Obama himself had to admit on 8 June that the US did not have a “complete strategy” to confront the jihadist group. The only clear winners in this deadlock are the weapons manufacturers, who have seen their sales skyrocket as the wars in the Middle East rage on.

Thousands of ISIS militants are believed to have been killed in battles and air strikes, but wide-ranging evidence shows that the number of international fighters has steadily increased over the last year, and that the recruitment channels continue to proliferate. This raises the prospect of possible terrorist blowbacks in other countries, as shown by the recent suicide bombings in the Eastern province of Saudi Arabia. In the wake of the rise of ISIS, new repressive measures and legislations are also adopted across the region and elsewhere, many of these laws will be also used to target political and trade union activists and to stigmatise Muslim populations in the West.

No genuine solution will come from the forces that have given birth to ISIS and religious fundamentalism in the first instance. Of course, one cannot totally rule out the possibility that the Western-led coalition might eventually manage to impose some decisive military blows to ISIS and to kick the jihadists out of some of the key territories they control. But even in case this happens, if the underlying conditions that enabled ISIS to flourish in the first place are not addressed, other similar or even more barbaric organizations are likely to take its place.

It is the task of the Iraqi and Syrian people to counter ISIS and not that of outside military powers. The developments of the last year have shown that outside interventions will only aggravate the situation for the masses of the region.

Some reports mention that the jihadists of ISIS have gone out of their way to try and win over the local Ramadi residents by trying to restart the providing of basic services in the city, handing out free food and vegetables. In Mosul, road-paving, cleaning and lighting projects have been witnessed. This seems to mark a conscious attempt by ISIS to try and regain a fading popularity. Eventually, the barbaric rule of ISIS, which wants to push history in reverse, stoning and beheading, enslaving teenage girls, destroying history and culture, banning films, music, and any slightest criticism to its suffocating and ultra-reactionary diktats, will inevitably push many Sunnis into resistance and open rebellion.

Tackling the root causes

Capitalism and imperialism, feeding themselves on devastating wars and mass poverty, are responsible for what is happening in the region. The working people, small farmers, unemployed, the youth and women of Iraq and Syria can only rely on their self-organisation to put an end to this nightmarish situation. At present, united i.e. non-sectarian self-defence of threatened communities and minorities is vital, and can be an important lever through which a grassroots movement fighting for democratic, economic and social change can be rebuilt.

By standing uncompromisingly against all imperialist forces, local reactionary regimes and sectarian death squads, and supporting the rights of self-determination for all communities, such a movement could find mass support among the regional and international working class. In their turn, workers’ organisations internationally need to spearhead movements against imperialist intervention in the Middle East, and be ready to support workers’ struggles breaking up in the region, such as the workers’ protests regularly taking place in Iraq against unpaid wages, privatisations, for trade union rights and other issues.

Cement workers in Karbala, Iraq, protesting for better working conditions and union rights, May 2015

In 2011, the popular reverberations in Iraq and Syria, of the revolutionary mass protests that shook North Africa and the Middle East have indicated that war and religious extremism are not a fatality for the people of the region. The long history and tradition of mass workers’ struggles in these countries, as well as the previous existence of powerful Communist Parties with mass bases of supporters across all religious and ethnic communities, amplifies this argument. Regrettably, the failed policies and betrayals by the Stalinist leaders of these parties, who collaborated with sections of the ruling classes, led to the almost total annihilation and irrelevance of these once mighty organizations.

Today, it is the lack of a mass left political alternative to right-wing religious forces, corrupt authoritarian rulers and imperialist meddling which has allowed the present nightmarish situation to unfold. But the horrific experiences of war and the poison of sectarianism will not prevent the workers’ movement from eventually re-emerging and rebuilding itself. For it to be viable, it will need to attach itself to a program aimed at respecting the right of all peoples and communities to freely and democratically decide their own fate, but also work towards putting the vast wealth of the region under people’s democratic control. A voluntary socialist confederation of the peoples of the Middle East would provide a lasting basis to put an end to war and barbarism in all its forms.