Julie Hyland

Each day brings ever more shrill warnings of a national crisis in the event of a no-deal Brexit.

With the March 2019 deadline for Britain's leaving the European Union (EU) approaching, no agreement has been struck on the terms of withdrawal.

Prime Minister Theresa May’s plans for a “softer” Brexit, keeping some form of regulatory and judicial arrangements with the EU, has been vetoed by her own euro-sceptics. At the same time, the EU, under pressure from US trade sanctions and mounting national antagonisms within the bloc, has thus far refused any accommodation with the UK—fearing a domino effect.

Government ministers, including May herself, are touring European capitals, hoping to secure a breach in the alliance. Brussels has rejected UK proposals for the City of London to have an enhanced “equivalence” model-similar to that of the US and Singapore’s-to preserve access to the bloc. The announcement earlier this week that Deutsche Bank has moved almost half of its euro-clearing business from London to Frankfurt created alarm.

On Wednesday, the head of the Food and Drink Federation called for a “crisis meeting” with the government over the probability that a hard Brexit—leaving the Single Market and Customs Union—would lead to rising prices and food shortages, under conditions in which 44 percent of trade is with the EU. The same day, planning documents from local authorities gathered by Sky Newsshowed that many were preparing for “possible repercussions of various forms of Brexit, ranging from potential difficulties with farming and delivering services to concerns about civil unrest.”

This followed statements by Dominic Grieve, Conservative MP and leading Remainer, that crashing out of the EU without a deal would be “absolutely catastrophic” for the UK. “We will be in a state of emergency,” he said. “[B]asic services we take for granted might not be available.”

John Manzoni, the chief executive of the civil service, told MPs of the “horrendous consequences” of inaction. “There are supply chains for food and medicines; we have to put in place contingencies for those.”

The contingency measures include turning the 10-mile-long section of the M26 in Kent into a giant lorry park to cope with tailbacks from the port of Dover caused by sudden imposition of customs checks. James Hookham, deputy chief executive of the Freight Transport Association, said, “It would effectively mean that Cobra [government emergency council] had taken over the road network as a matter of national security.”

May rejected suggestions that the army would be involved but has said people should “take comfort” from government plans, including the stockpiling of food and medicines, in the event of no deal. The government is to start issuing weekly advice to businesses and households on how to prepare for a “disorderly” Brexit.

According to reports, 40 business representatives met with Brexit Secretary Dominic Raab, during which Doug Gurr, head of Amazon in the UK, warned of “civil unrest” if the UK leaves without a deal.

Amazon would not confirm the remarks, apparently made in the presence of the heads of Barclays, Lloyds, Shell and other corporate leaders, but admitted it was planning for a wide range of outcomes. Aerospace giant Airbus and Jaguar Land Rover have already warned they may switch jobs and investment outside the UK.

Commentators speculate that the apocalyptic warnings are part of the government’s political brinkmanship with the EU to reinforce its insistence that the UK will not blink first.

For their part, leading supporters of a hard Brexit reject the threats as “Project Fear” by Remainers in furtherance of overturning the referendum result.

Both play a role.

Writing in the Guardian, one of the leading proponents of a second referendum to overturn the result of the first, Timothy Garton Ash, warned that a no Brexit deal risked “descent into Weimar Britain.”

While he didn’t seriously envisage, “a new Hitler coming to power, or a world war started by [former foreign secretary] Boris Johnson,” he wrote, it was necessary to “overdramatise the risk” in order to “get everyone to wake up to it.”

Pleading for EU/UK pragmatism, he argued this was the only way to ensure the British parliament could have a “meaningful vote” on the final terms.

But even the Financial Times editorialised that “the notion of a no-deal Brexit had little support in parliament beyond an extremist fringe...”

No deal in place by March guaranteed “chaos on all fronts. It would spell international isolation, as well as a shock to the economy and a political backlash. No competent government could contemplate such an option.”

The sense of impending doom overhanging the powers-that-be confirms the correctness of the Socialist Equality Party’s call for an active boycott of the 2016 referendum. It warned that the ballot was a filthy manoeuvre aimed at settling a fight between two equally right-wing factions of the Tory Party and its fringes. The campaign of both the Leave and Remain camps were predicated on anti-migrant chauvinism, kowtowing to big business and continuing austerity.

The SEP explained, “There can be no good outcome of such a plebiscite. Whichever side wins, working people will pay the price. It is not a question of choosing the ‘lesser evil’—both options are equally rotten. Any possibility of an independent voice for the working class being registered has been deliberately excluded.”

A significant element of the referendum, it insisted, was an attempt to divert social tensions outwards. Pointing to the initial manifestations of a resurgence in the class struggle, it stressed that the only way forward for British workers was in solidarity with the working class across Europe and internationally against all factions of the ruling elite.

None of those involved in this manoeuvre expected or prepared for a Leave vote. All were taken by surprise when a well of anti-establishment sentiment produced a narrow vote to quit.

Underlying the result, and the febrile atmosphere that has developed since, are explosive class tensions. This is being acknowledged by some commentators.

Writing in the Financial Times, Martin Sandbu opined that Brexit showed the days in which Britain was riven by extremes.

“To borrow a Marxian term,” he explained, “the social contradictions are more acute than elsewhere...”

This was the only way to make sense of the “violent swings in national direction... Bringing to the surface the repressed tension of British society leaves deep uncertainty about how those contradictions are ultimately resolved. That is the thing with opposed extremes: their force may give the semblance of stability to the revolution simmering underneath.”

“The greater a society’s contradictions, the more disruptive the snap is when it comes.”

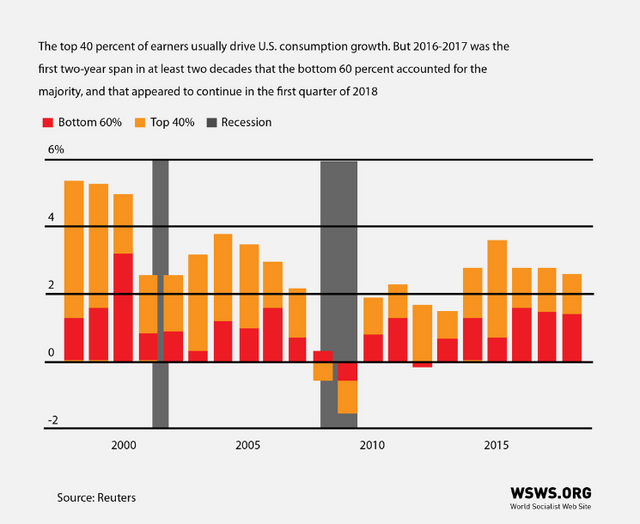

In the Telegraph, Jeremy Warner wrote that “the root cause of Britain’s distress is all too obvious—too many people scratching a living in rubbish, low wage, low productivity, dead end jobs, and the all too evident social alienation that goes with such a dispiriting state of affairs.”

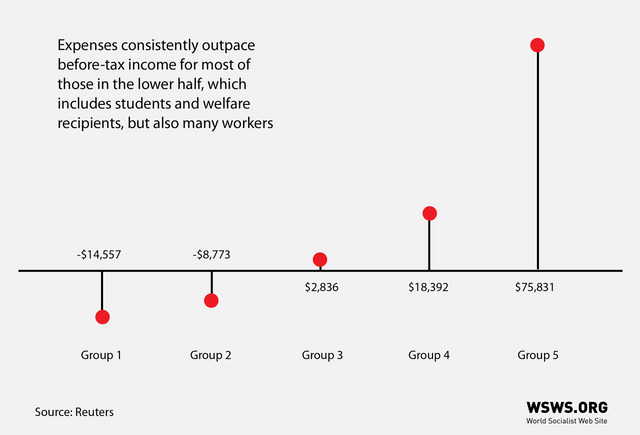

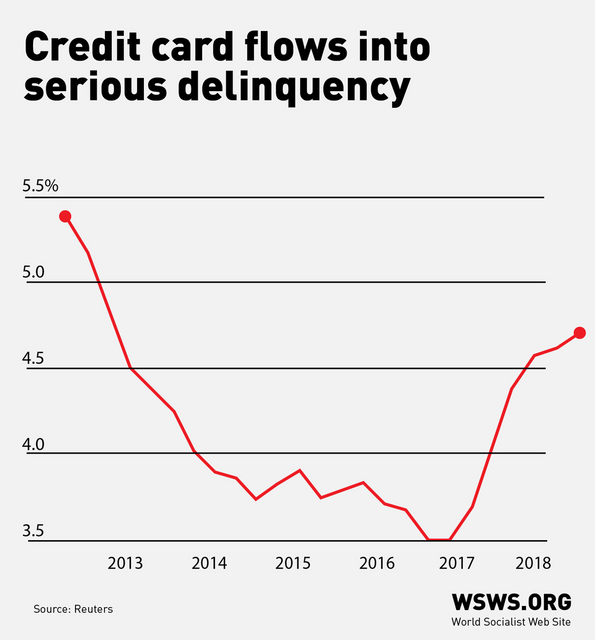

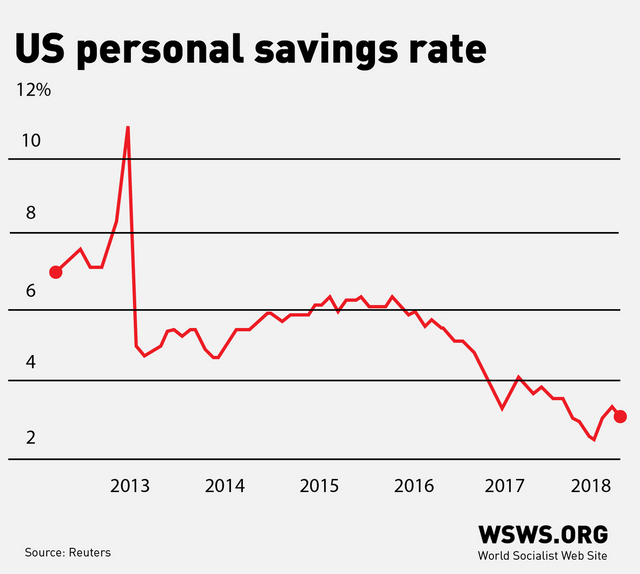

Warner was commenting on a report by the Office for National Statistics that showed that for the first time since Margaret Thatcher’s government, households were spending more than they earned. The average family was £900 in the red last year, with a total national shortfall of £25 billion—and only managing to keep afloat through credit or savings.

Even at the time of the 2008 financial crisis, the ONS warned, “the country did not reach a point where the average household was a net borrower.”

The richest 10 percent of households had disposable income—after taxes and housing costs—of more than £78,000 last year, of which they spent less than half. In contrast, the poorest 10 percent had disposable income of just £5,000 but spent nearly £13,000. Financial experts warned that such debt was “unsustainable” and “profoundly worrying.”