Benjamin Mateus

UnitedHealth Group Inc. brought a lawsuit earlier this year against a former information technology executive, David Smith, accusing him of stealing trade secrets and taking them to his new employer. This was the still unnamed joint venture known as ABC, a healthcare initiative that was launched in 2018 by Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway and JPMorgan Chase that supposedly intends to address the bloated health industry’s inefficiencies and high costs.

In a brief presented in a Boston federal courtroom by attorneys representing United’s Optum unit, they stated, “On the same day that he [David Smith] talked with ABC, and just one minute before printing his resume, Smith printed an Optum document marked ‘confidential’ that contains, among other things, Optum’s highly confidential information including an in-depth market analysis of the healthcare industry.”

Smith denied these charges and argued that he and ABC are not competing with UnitedHealth and are partnering in a not for profit with the intent to reduce healthcare costs among the three companies’ employees. Presently, Optum is providing healthcare services for Berkshire and JPMorgan. In his new position at ABC, Mr. David Smith will be director of Product Strategy and Research.

US District Judge Mark Wolf rejected UnitedHealth Group’s effort to block their former employees from joining ABC and ordered the case to be moved to arbitration as requested by ABC and Smith’s legal team.

That UnitedHealth Group, the largest healthcare company in the world by revenue (earning $226.2 billion in 2018) and ranked sixth in the 2019 Fortune 500, views this initiative by ABC with trepidation suggests a major shift is taking place in the healthcare market, in which high-tech companies are considered direct hostile competitors.

Given the rapid developments in digital technology over the last two decades these fears are warranted as capital seeks to channel financial transactions through more efficiently exploitive channels. These unfolding legal maneuvers are the initiation of volleys in a rapidly developing turf war.

American businesses and Wall Street corporations remain quite attentive to developments in the three corporate giants’ venture into the health industry. Approximately 46 percent of all Americans get their health insurance through an employer. Amazon, Berkshire Hathaway and JPMorgan Chase have nearly 1.2 million employees combined.

To comprehend what’s gnawing at the psyche of these corporate conglomerates, it helps to appreciate the enormous crisis facing the healthcare industry.

Soaring healthcare costs

A Kaiser Family Foundation 2017 employer survey found annual premiums for employer-sponsored family health coverage reached an average of $18,764, up 3 percent from the previous year, with workers contributing $5,714 towards the cost of their coverage. Though wages have barely kept up with inflation, with a paltry 26 percent rise since 2008, annual deductibles are rising eight times faster, with a 212 percent increase in the same period.

Startling statistics indicate that though the US population has expanded by 75 percent since 1960 to approximately 325 million people, healthcare expenditures, in constant dollars, have risen approximately 2000 percent.

US healthcare spending grew 3.9 percent in 2017, reaching $3.5 trillion, or $10,739 per person. As a share of the gross domestic product (GDP), health spending accounted for 17.9 percent, up from 6.9 percent in 1970. Spending is projected to grow at an average rate of 5.5 percent annually, reaching over $6 trillion by 2027 (19.4 percent of GDP). Healthcare expenditures continue to outpace GDP.

This spike in spending is not being driven by demand but by price hikes, despite evidence that these expenditures are not leading to improvements in health outcome measures. Since 2000, drug prices have risen 69 percent, hospital costs 60 percent, and physician/clinical services 23 percent.

The US population is facing a serious health calamity which is fueling these dire economic statistics. Though healthcare spending had historically been skewed toward the eldest in the population, recent analysis finds health spending has become less concentrated among the elderly, with healthcare dollars shifting across a broader swath of the population.

Whereas 56 percent of spending was concentrated among the top 5 percent in 1987, this group accounted for just under half of spending in 2009. Similarly, the spending share for the top 1 percent fell from 28 percent in 1987 to about 22 percent in 2009.

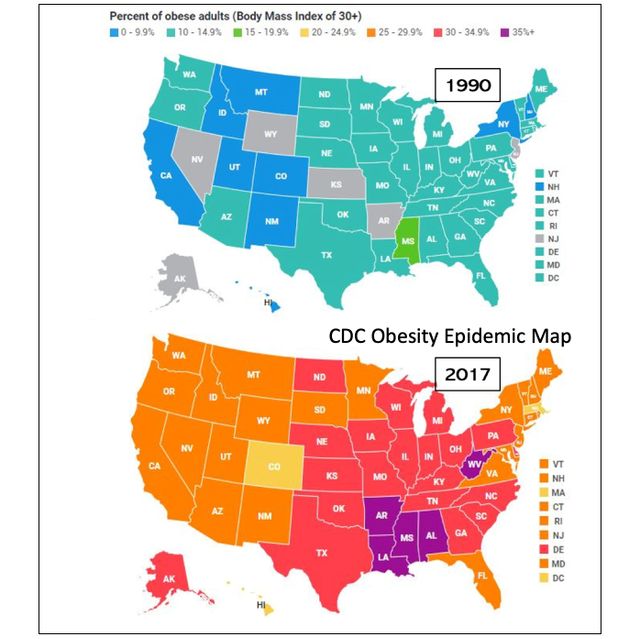

Credit: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

Credit: Centers for Disease Control and Prevention

The explanation for this flattening is primarily driven by the obesity epidemic. Younger age groups which used to be healthier are now experiencing rising prevalence of chronic diseases like high blood pressure, diabetes and high cholesterol. These, in turn, contribute to increased risks of heart disease, stroke, kidney failure, immobility from joint ailments, and even malignancies.

Incredulously, one-third of healthcare spending isn’t helping anyone. The administrative burden in the US health markets is unique in creating glaring inefficiencies. There are hundreds of health insurance plans all charging different prices for the same surgeries and diagnostic studies. For every three doctors there are two administrative staffers to handle the paperwork. Over $765 billion is wasted each year, with $210 billion being charged in unnecessary services, $190 billion in high administrative costs, $130 billion in inefficiently delivered services, $105 billion in exorbitantly high prices, $75 billion in fraud and $55 billion in missed prevention opportunities.

The profit potential in health dollars has not been missed on high-tech companies. A JPMorgan Chase Institute study from 2015 cited that the number of people who earn income through online platforms has increased 47-fold in three years. In 2014, 24.9 million individuals filed tax returns indicating that they were the owners of a sole proprietorship. This represented a 34 percent increase in self-employment since 2001.

According to John Boitnott writing for Inc., when the Affordable Care Act went into effect in 2014, 1.4 million or 1 in 5 purchasing coverage were considered self-employed or small business proprietors. By 2020, independently employed persons are expected to comprise 40 percent of the economy. Initiatives and coalitions by these high-tech companies to capture these “clients” have been underway.

What the ABC health initiative may demonstrate is that, by selling their own workers marginally less costly “comprehensive health insurance,” companies could potentially redirect billions back into their own pockets. Rather than providing their workers with the healthcare they deserve, they would shift the burden further on the backs of workers by garnering their wages for healthcare services promised. These developments are reminiscent of the exploitation workers faced in traditional company towns. Current experiences by Amazon workers and the outcomes of their on-the-job injuries should be a stark lesson.

Since the 2018 health initiative, Amazon has gone on to purchase the online pharmacy startup PillPack for $1 billion while also planning to develop and sell software that will read medical records. PillPack is a full-service ePharmacy that fills prescriptions and ships drugs packaged in pre-sorted doses. Stock prices for traditional drugstore operators like CVS, Rite Aid and Walgreens fell on news of this deal.

Tech companies’ forays into healthcare

Apple updated its Apple Health app in 2018, allowing it access to medical records from 39 hospitals. It also has received clearance from the FDA for various cardiac rhythm monitor apps that allows users to track their heart status. They have also opened an on-site clinic for their employees and are delving into online medical records initiatives.

Uber, the ride-sharing company, has ventured into the $3 billion medical transit market, offering non-medical-emergency transportation to the sick and elderly who often can’t drive. Most of the money comes through Medicare and Medicaid providers who foot the bill for their patients. It is estimated that 3.6 million people miss their healthcare appointments every year due to unreliable transportation, with an estimated $150 billion impact on healthcare expenditure.

Alphabet is the parent company of Google and is focusing on health research by incorporating technology in assisting physicians to take notes, assisting the elderly in nursing homes, and creating algorithms for predicting heart disease by looking into the patient’s eyes. They are also partnering with Walgreens to create technology addressing medical noncompliance and misuse of medications.

Last month, during President Trump’s State Visit to London, he included in his remarks that access to British public health system’s data should be part of trade talks after Brexit had taken effect. The UK National Health System has been a “free to use” entity for seven decades and attempts to monetize and privatize its massive data banks has been deeply unpopular. Despite the public’s deep opposition to any privatization of their national healthcare, Prime Minister Theresa May could only feebly add that “the point of making trade deals is both sides negotiate.” Under developing circumstances, the UK will be hard pressed as the much smaller and disadvantaged negotiating partner.

Polls indicate that three-quarters of the British public is in favor of the use of artificial intelligence to develop and improve diagnostic tools for treatment and prevention of illness. But there is healthy mistrust of big tech companies and multinationals that stand to amass fortunes should they be given access to the national database that has detailed information on 65 million lives.

According to the Guardian, “While other countries’ datasets are more fragmented, the NHS database has comprehensive patient records that go back decades. This treasure trove is priceless to technology giants such as Google’s parent Alphabet as well as smaller healthcare firms, which are vying to develop health mobile phone apps that perform a host of tasks from monitoring vital organs to carrying out an initial diagnosis.”

These maneuvers by Amazon and high-tech companies are intended to wedge themselves, through monopoly practices, into these traditional industries where inefficiencies mean lucrative opportunities at the cost of improvements in real health measures for working people. The working class must wrest these technological developments created by their own hands out of the clutches of the financial sector and redirect them for the real benefit of mankind.