Stephan McCoy

Michael Yao, the World Health Organisation’s (WHO) Africa programme manager for emergency response, has warned of a rapid increase in coronavirus cases on the continent. Noting that, “During the last four days, we can see that the numbers have already doubled,” he added, “If the trend continues, and also learning from what happened in China and in Europe, some countries may face a huge peak very soon.”

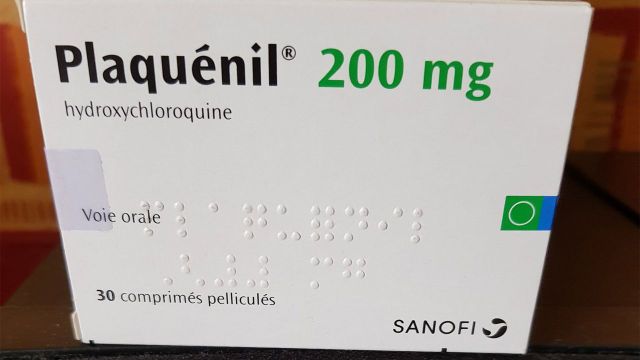

Far more so than in Europe and China, Africa’s health systems are woefully underfunded, understaffed and under-resourced. There is a vital need for a vaccine, but chances of obtaining one in less than 18 months are slim to nil. Under these conditions, Uganda’s government has taken a leaf from US President Donald Trump’s playbook in touting untested remedies, chiefly the anti-malarial drugs chloroquine (CQ) and hydroxychloroquine (HCQ), as a potential lifesaver.

According to PML Daily, “Director of Health Services, Ministry of Health, Henry Mwebesa has revealed that [three recently discharged patients] who had tested positive [for the] Coronavirus were treated using the controversial hydroxychloroquine drug, that was used in the 90s and early 2000s to treat malaria.”

Plaquenil is one of many brand names for the drug Hydroxychloroquine. (Photo credit: Twitter/Manon01901750)

Plaquenil is one of many brand names for the drug Hydroxychloroquine. (Photo credit: Twitter/Manon01901750)

Mwebesa tweeted, “The patients we are discharging today were on hydroxychloroquine and erythromycin actually.” He made his remarks in response to one of his followers, Brandon Ndoni, who asked the Ugandan government to clarify the controversy over the use of CQ and HCQ in light of the fact that the “WHO, Europe (bar France) are yet to authorize use of Antimalarials Hydroxychloroquine, Chloroquine in treating Covid-19 pneumonia.”

Health Minister Dr Jane Ruth Aceng sought to justify this, telling a press conference in Kampala that, although HCQ is still undergoing testing, it can stop the spread of the disease by stabilizing red blood cells and promoting the uptake of oxygen.

The government’s endorsing of HCQ and CQ has helped promote panic buying and stockpiling of the drugs.

In February, Janet Diaz, head of clinical care for the WHO Emergencies Program, answered a reporter’s question about CQ at a press conference, saying that there was no proof yet that it was an effective treatment.

Just last week, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention updated their therapeutic options guidance, removing any reference to HCQ and stating explicitly, “There are no drugs or other therapeutics approved by the US Food and Drug Administration to prevent or treat COVID-19.”

Having spent decades slashing health care systems and starving them of resources, African governments are attempting to promote HCQ and CQ as quick-fix cures to conceal the impact of privatisation and budget cuts carried out at the behest of the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank as the condition for loans.

While the WHO reiterates that mass testing, contact tracing, isolation and treatment are the most effective ways to fight the virus, African governments—like their counterparts in the advanced industrial countries— refuse to mobilize the necessary resources to fight the virus.

President Yoweri Museveni, in power since 1986, has spent his years in office giving away Ugandaʼs assets to international financial interests and carrying out a punishing series of privatisations. This wholesale robbery and looting of resources on behalf of international capital and its local agents has had a catastrophic effect on the working class and poor farmers.

In 2017, the country ranked 162 out of 189 on the UN’s Human Development Index. Three-quarters of the population lives on less than $3.10 per day. Life expectancy is just 62 years, only two years more than war-torn Democratic Republic of Congo; 51 percent of Ugandans lack access to safe water; 82 percent do not have access to improved sanitation facilities; and acute malnutrition (wasting) among children between six months of age and five years old is four percent, but 10 percent in the West Nile sub-region of Uganda.

In a bid to stop the virus spreading, the government ordered a lockdown at the beginning of April. But with 71 percent of people who live in the capital, Kampala, sharing a one-roomed home with several others, this is a terrible ordeal.

There is a ban on all transport and a night-time curfew, now extended beyond the initial two weeks for a further three weeks, amid a national power outage. Security forces have fired on people violating the curfew. The ban on all private and public transport extends even to medical emergencies, and at least seven pregnant women have died as a result of the lockdown.

Scovia Nakawooya’s unborn child died inside her as she struggled to reach a hospital on foot. Her husband Francis Kibenge begged drivers to take her to a hospital a mile and a half away. Grace Nagawa, the couple’s 19-year-old daughter, wept as she explained, “Sometimes she would stop, bend and put her hand on her thigh to support her body, just to rest a bit.” Nakawooya died at the medical centre the next morning.

The situation facing the country, which hosts Africa’s largest refugee population—1.4 million from neighbouring DRC and South Sudan—is dire. Julius Kasozi, a public health officer with the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR) in Uganda, said, “I fear a high death toll if the virus reaches the settlements.”

As well as all the other restrictions, the lockdown bans the movement of refugees outside these settlements, preventing them from getting food rations and other essentials. The UN’s World Food Programme has announced a 30 percent reduction in the rations it distributes to refugees due to a loss of 67 percent of its funding for East and Central Africa.

A second locust swarm that is sweeping East Africa and the Horn is devouring newly planted crops and livelihoods in its path. It is expected that poor farmers and semi-nomadic herders in the east and the semi-arid northeast Karamoja region will be the hardest hit, even as the coronavirus sweeps the country. The flight and travel bans imposed to stop the spread of the virus mean that much needed pesticides and international personnel to fight the locusts are not available.

While the government has urged farmers to start planting to ensure food security, Loupa Pius, project officer at Dynamic Agropastoralist Development Organisation in Karamoja, told Al Jazeera, “People should be advised to halt planting of crops to observe the direction and the stage of desert locust outbreak.

“Otherwise, if this is not taken into action, the usual food insecurity will override the region, including capable people who can usually easily find their own food without aid. This time round, they are likely to ask for it because the situation has been hit by COVID-19.”

The United Nations is already warning that the locust swarm could increase 500-fold by June.