Yash Vardhan Singh

The India-Nepal territorial dispute around the Kalpani-Limpaidhura-Lipulekh trijunction area stems only in part from the ambiguity around the original boundary settlement. The present flare up is a result of a combination of factors: India’s strategic concerns; deterioration in India-Nepal relations; Beijing’s steady inroads into Nepal; and deteriorating India-China relations.

A Brief Overview of India-Nepal Border IssuesThe India-Nepal border was originally delineated by the 1816 Sugauli Treaty, which established the river Kali (Sharda, Mahakali) as the boundary, with territory east of the river going to Nepal. The Kalapani-Limpaidhura-Lipulekh trijunction territorial dispute centres on the source of the River Kali. Nepal’s stance is that that the river originates from a stream north-west of Lipulekh, bringing Kalapani, Limpiyadhura, and Lipulekh within its territory. India’s stand is that the river originates in springs below the Lipulekh, and therefore the area falls within Pithoragarh District in India’s Uttarakhand state. Both sides have British-era maps to assert their positions.

Recent Flare-UpIndia recently inaugurated the Darchula-Lipulekh pass link road, cutting across the disputed Kalapani area, which is used by Indian pilgrims travelling to Kailash Mansarovar. The Nepalese government protested this move, pointing out that the construction of the road amounted to territorial encroachment. Kathmandu subsequently released a map displaying the tri-junction area as Nepalese territory. India responded by releasing maps that supported its position, and called for talks for a resolution of the impasse.

However, Nepal granted constitutional validity to its stance through the introduction of a constitutional amendment, and began tightening border security measures. Two days after the inauguration of the link road, Nepal’s foreign minister said that the country plans to increase border security posts along the India-Nepal border, which according to him were inadequate in comparison to India’s. This is a departure from the status quo, and points towards a hardening of this international boundary.

China FactorThe tension over this territorial dispute stems from the fact that it is a strategic trijunction between India, China, and Nepal. The Kalapani area is under India’s control with Indo-Tibetan Border Police (ITBP) observation posts. Increased connectivity in border areas is critical for border patrolling and quick mobilisation, and New Delhi views it as being crucial for dealing with “difficult neighbours.”

Control of the Kalapani trijunction enables India to position itself at a physically strategic elevation, allowing Indian posts to monitor the Tibetan highland passes, which could prove crucial in the event of a Sino-Indian conflict. This consideration was vindicated in the 2017 India-China military standoff in Doklam, during which Chinese officials stated that China’s Peoples Liberation Army (PLA) could enter India with ease through other border trijunctions like Kalapani or Kashmir. In 2020, following the inauguration of the road by India, Nepal’s Armed Police Force (APF) set up a new border post close to Lipulekh. The APF is a paramilitary wing in which China has invested heavily.

Recent political developments in Nepal, with the National Communist Party (NCP) coming to power, has increased China’s influence in Kathmandu. Beijing has been involved in managing rifts within the NCP—the most recent one was in May 2020—which is indicative of Beijing’s influence on the country’s politics. Increasing Chinese investment in physical infrastructure like the trans-himalayan railways, and Nepal joining the Belt and Road Initiative (BRI), etc. point to Beijing’s growing economic influence as well.

On the other hand, despite the long history of bilateral relations, the India-Nepal relationship has often run into problems in the past decade. For example, being a landlocked country, Nepal depends considerably on India for access to essential goods. The alleged ‘unofficial blockade’ of 2015 by India, which led to disruption of essential fuel supplies during the Madhesi protests in Nepal, further dented bilateral trust. This incident spurred Kathmandu to strengthen its alternative to India, thereby intensifying its tilt towards China.

Big PictureThere is possible correlation between Chinese strategic objectives and the revived Nepalese claim on Kalapani, despite Nepal’s Prime Minister Oli stating that “everything we do is self-guided.” To illustrate, despite frictions, New Delhi and Kathmandu have already made substantial past strides towards the resolution of the border dispute. The two countries had established a Joint Technical Level Boundary Committee to delineate their common borders and resolve territorial disputes. By 2007, this joint initiative led to 98 per cent of the 1850-km border being delineated. The two sides have also used high-level bilateral channels to keep border disputes from flaring up in the past.

In the big picture of deteriorating China-US relations, Beijing is increasing pressure along borders to deter India’s alignment with the US, and to assert itself as an ascendant power in the post COVID-19 world order. The possibility of Chinese influence over the Nepalese government to exhibit hostility towards India also fits into the wider pattern of Beijing’s aggressive posturing vis-à-vis Hong Kong, Taiwan and the South China Sea. The spike in India-Nepal tensions coincides with India’s rising border tensions with China in Ladakh and Sikkim. Overall, there are clear indications suggesting that Beijing is leveraging its relationship with Nepal to put indirect pressure on India.

10 Jul 2020

India: Beyond the Binary of Whether to Talk to the Taliban

Rajeshwari Krishnamurthy

In the backdrop of a US-backed negotiated settlement attempt in Afghanistan gaining momentum, the debate on talking to the Taliban has resurfaced in India, particularly through May 2020. There may be some potential advantages India could gain by talking to the Taliban but these are still notional at this juncture. Therefore, India’s decision-making will need to consider more than just a basic binary of talking or not talking.

Recent Developments

In May 2020, US Special Representative for Afghanistan Reconciliation, Zalmay Khalilzad, as well as the US Department of State’s outgoing Principal Deputy Assistant Secretary of State for South and Central Asia, Alice Wells, strongly urged that India engage with the Taliban. The Taliban has also sought engagement with India.

On 18 May, the Taliban’s Doha-based Spokesperson, Suhail Shaheen, made seemingly conciliatory remarks regarding the group’s stance on India, stating that the Taliban “does not interfere in the internal affairs of other countries.” In a 19 May interview, he derided those in India questioning the merits of talking to the group as “not speaking for the interests of the people of India.”

Despite Shaheen’s claim of non-interference, the Taliban has not yet indicated such plans or its enforcement ability for better relations with India. This is relevant because the Haqqani Network continues to be an integral part of its structures, and the Taliban’s relationship with al Qaeda and other terror outfits targeting India, including Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT), Jaish-e-Muhammad (JeM), etc, is still active.

Furthermore, Shaheen’s dismissive remarks of 19 May regarding Indians echo a divisive rhetoric the Taliban has for long practiced vis-à-vis Afghans who raise critical questions regarding the group’s conduct or intentions. This is pertinent given how, in Afghanistan, there is a willingness for reconciliation with Taliban members but not with the group’s ideology.

Relevant Considerations

Revelations contained in the May 2020 UN report on the status of the Taliban’s linkages and decision-making agency inspire no confidence. In the absence of the Taliban demonstrating tangible actions to enforce its stated intentions (in the US-Taliban agreement and elsewhere), it might not be beneficial for India to commence direct talks at this stage. Doing so would aid international legitimisation of the Taliban prematurely, which will not only undermine the Afghan government’s negotiating power during the intra-Afghan negotiations (IAN), but also contribute towards setting undesirable precedents, such as side-lining a sovereign government and giving mileage to a terrorist group.

If Taliban leaders genuinely wish to establish a non-adversarial relationship with India, they should be okay with such engagement beginning after the group has ended insurgency and been assimilated into Afghan society by peaceful means. The only scenarios where this would not apply are:

a) If the Taliban’s intentions towards India are conditional upon New Delhi commencing direct engagement with the group before or during the IAN

b) If direct India-Taliban talks at this juncture is not a necessity but merely something that delivers the Taliban tactical and narrative gains through New Delhi’s legitimisation of them.

b) If direct India-Taliban talks at this juncture is not a necessity but merely something that delivers the Taliban tactical and narrative gains through New Delhi’s legitimisation of them.

Neither of the two scenarios nor current ground realities warrant a policy change from India.

In India, both those for and against talks seem to agree upon one scenario as a potentiality. If Taliban members are assimilated into Afghanistan’s governance structures via an inclusive, Afghan-led, -owned, and -controlled process, those members may eventually be inclined to shake off the Pakistani yoke to act more independently. While this argument has potential, sweeping policy change cannot rely solely on the future prospect of a singular hypothetical scenario. However, if New Delhi opts to formally begin communication with the Taliban before the IAN concludes, it would be prudent for India to:

a) Initiate communication only after the IAN begins and shows meaningful progress

b) Refrain from high-level engagement from the Indian side—i.e. cap it at ambassador-level

c) Set terms and conditions for commencement, coordination, and continuation of such engagement. This would involve compartmentalising engagement into different stages, with progression to each stage conditional upon the Taliban’s delivery of certain tangibles; and institutionalising prior coordination between New Delhi and Kabul as part of the engagement framework

d) Determine the preferred venue—for e.g., New Delhi need not play host to the Taliban for talks. Frequent international travel by the Taliban to meet with government representatives ends up contributing to the group’s international legitimisation prematurely

e) Determine issues New Delhi will and will not discuss—for e.g., focus on current issues of concern to India that pertain specifically to the Taliban. Issues such as future economic cooperation, which falls within the official government category, should be outside of the purview of such a template

f) Set publicity protocols—i.e. determine information that will be made available publicly at each stage, timing, and the platforms.

b) Refrain from high-level engagement from the Indian side—i.e. cap it at ambassador-level

c) Set terms and conditions for commencement, coordination, and continuation of such engagement. This would involve compartmentalising engagement into different stages, with progression to each stage conditional upon the Taliban’s delivery of certain tangibles; and institutionalising prior coordination between New Delhi and Kabul as part of the engagement framework

d) Determine the preferred venue—for e.g., New Delhi need not play host to the Taliban for talks. Frequent international travel by the Taliban to meet with government representatives ends up contributing to the group’s international legitimisation prematurely

e) Determine issues New Delhi will and will not discuss—for e.g., focus on current issues of concern to India that pertain specifically to the Taliban. Issues such as future economic cooperation, which falls within the official government category, should be outside of the purview of such a template

f) Set publicity protocols—i.e. determine information that will be made available publicly at each stage, timing, and the platforms.

Looking Ahead

Since July 2018, when direct US-Taliban talks began, a considerable portion of international engagement with the group has taken place on the basis of the Taliban’s rhetoric of action in the future. In its rhetoric, the Taliban has punctuated claims regarding commitment to peace, women’s rights, compliance with international law and norms, etc, with ambiguous caveats.

Therefore, New Delhi’s policy choices on engaging with the Taliban will have to be based on its own priorities, as well as the group actually delivering on its commitments. India’s strategy will need to take into account the timing, format, and content of talks as equally important factors if New Delhi is to benefit in a way that is long-lasting and value-based. At all times, Afghanistan’s own efforts must be centre stage.

9 Jul 2020

Japan-WCO International Masters Scholarships 2021 for Young Customs Officials in Developing Countries

Application Deadline: 10th August 2020

Offered annually? Yes

To be taken at (country): Aoyama Gakuin University (AGU) Tokyo, Japan

Accepted Subject Areas? Strategic Management and Intellectual Property Rights (IPR)

About Scholarship: The Japan-WCO Human Resource Development Programme (Scholarship Programme) provides a grant covering travel, subsistence, admission, tuition and other approved expenses to enable promising young Customs managers from a developing member of the WCO to undertake Master’s level studies at the Aoyama Gakuin University (AGU) in Tokyo, Japan.

The Scholarships in Japan provides Customs officials from developing countries with an opportunity to pursue Master’s level studies and training in Customs related fields in Strategic Management and Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) at the university in Tokyo, Japan.

The Master degree programme comprises two segments: an academic segment and a practical segment. The academic segment starts with focused teaching of foundational skills in strategic management and IPR. It then moves to a range of applied topics which help students understand how to design, implement, and evaluate public policies, in particular customs policy, in accordance with development strategies for organizations. The practical segment is taught in co-operation with the Japan Customs, including the Japan Customs Training Institute.

Type: Masters

Who is qualified to apply?

What are the benefits?

How to Apply: Candidates interested in applying for the scholarship should submit applications for admissions for the 2020/2021 Programme. ID and Password for the online application will be obtained by submitting the ONLINE REGISTRATION FORM (Link is at the top right corner of the Scholarship Webpage. When registering, enter Login ID and password of your own choice and indicate your interest in the WCO Scholarship) on the Web site by the application deadline.

Visit Scholarship Webpage for Details

Offered annually? Yes

To be taken at (country): Aoyama Gakuin University (AGU) Tokyo, Japan

Accepted Subject Areas? Strategic Management and Intellectual Property Rights (IPR)

About Scholarship: The Japan-WCO Human Resource Development Programme (Scholarship Programme) provides a grant covering travel, subsistence, admission, tuition and other approved expenses to enable promising young Customs managers from a developing member of the WCO to undertake Master’s level studies at the Aoyama Gakuin University (AGU) in Tokyo, Japan.

The Scholarships in Japan provides Customs officials from developing countries with an opportunity to pursue Master’s level studies and training in Customs related fields in Strategic Management and Intellectual Property Rights (IPR) at the university in Tokyo, Japan.

The Master degree programme comprises two segments: an academic segment and a practical segment. The academic segment starts with focused teaching of foundational skills in strategic management and IPR. It then moves to a range of applied topics which help students understand how to design, implement, and evaluate public policies, in particular customs policy, in accordance with development strategies for organizations. The practical segment is taught in co-operation with the Japan Customs, including the Japan Customs Training Institute.

Type: Masters

Who is qualified to apply?

- A candidate must be a customs officer of a developing member of the WCO with quality work experience of at least three years in the field of customs policy and administration in his/her home country.

- Preference will be given to candidates who have experience in IPR border enforcement, and who are expected to work in the IPR-related section of their Customs administration after this Scholarship Programme.

- A candidate must be in good health and preferably under 40 years of age as of April 1, 2021.

- Individuals who have already been awarded a scholarship under the Japan-WCO Human Resource Development Programme in the past will not be entitled to apply for this Scholarship Programme.

- After the completion of the Programme, the candidates should continue to work in their home Customs administration for 3 years at least.

What are the benefits?

- A monthly stipend covers accommodations, meals, transportations, and other expenses. It cannot be increased to cover family members, if any. The amount of stipend is subject to change according to the decision of the Japanese Government.*

- Admission and tuition fees.**

- Round-trip economy-class air tickets between your home country and Japan. *The current amount of monthly stipend is 147,000 yen (as of 2020).

**The current amount of admission fee is 290,000 yen and annual tuition fee is 917,000 yen (as of 2020).

How to Apply: Candidates interested in applying for the scholarship should submit applications for admissions for the 2020/2021 Programme. ID and Password for the online application will be obtained by submitting the ONLINE REGISTRATION FORM (Link is at the top right corner of the Scholarship Webpage. When registering, enter Login ID and password of your own choice and indicate your interest in the WCO Scholarship) on the Web site by the application deadline.

Visit Scholarship Webpage for Details

Princeton Arts Fellowships 2021/2023 for International Early-Career Artist(e)s

Application Deadline: 15th September 2020 at 5:00 p.m. (EDT).

Eligible Countries: All

To Be Taken At (Country): USA

About the Award: The PAF is a two-year fellowship that includes teaching one course or leading a project each semester.

Type: Fellowship

Eligibility: Artists whose achievements have been recognized as demonstrating extraordinary promise in any area of artistic practice and teaching.

Eligible Countries: All

To Be Taken At (Country): USA

About the Award: The PAF is a two-year fellowship that includes teaching one course or leading a project each semester.

Type: Fellowship

Eligibility: Artists whose achievements have been recognized as demonstrating extraordinary promise in any area of artistic practice and teaching.

- Applicants should be early career composers, conductors, musicians, choreographers, visual artists, filmmakers, poets, novelists, playwrights, designers, directors and performance artists–this list is not meant to be exhaustive–who would find it beneficial to spend two years teaching and working in an artistically vibrant university community.

- One need not be a U.S. citizen to apply.

- Holders of Ph.D. degrees from Princeton are not eligible to apply.

- This fellowship cannot be used to fund work leading to a Ph.D. or any other advanced degree.

Number of Awards: Not specified

Value of Award: An $81,000 a year stipend is provided.

Duration of Program: 2 years

How to Apply: All applicants must submit a resume or curriculum vitae, a personal statement of 500 words about how you would hope to use the two years of the fellowship at this moment in your career, and contact information for three references. In addition, work samples are requested to be submitted online (i.e., writing sample, images of your work, video links to performances, etc.)

APPLY HERE

Visit the Program Webpage for Details

Value of Award: An $81,000 a year stipend is provided.

Duration of Program: 2 years

How to Apply: All applicants must submit a resume or curriculum vitae, a personal statement of 500 words about how you would hope to use the two years of the fellowship at this moment in your career, and contact information for three references. In addition, work samples are requested to be submitted online (i.e., writing sample, images of your work, video links to performances, etc.)

Applicants can only apply for the Princeton Arts Fellowship twice in a lifetime.

APPLY HERE

Visit the Program Webpage for Details

Venezuela is on a Path to Make Colonialism Obsolete

Nino Pagliccia

On June 29 the European Union (EU) slapped new sanctions against 11 Venezuelan individuals. Immediately President Nicolas Maduro responded by ordering the expulsion of the EU ambassador to the country. EU foreign policy chief Josep Borrell warned that Brussels would retaliate against Caracas over its decision and announces that it will summon Maduro’s ambassador to the European institutions. That never happened. Instead Josep Borrell called on Venezuela to reverse its decision. On July 1 the Venezuelan government decided to rescind its decision to expel the head of the EU mission in Caracas following a phone conversation between Venezuela’s Foreign Minister Jorge Arreaza and the high representative of the European Union for Foreign Affairs and Security Policy, Josep Borrell, and issuing a joint communiqué.

This sequence of events gives a diplomatic victory to the Maduro government. It may be the victory of a schoolyard bullied youth who stands up after every blow from the bully. The strikes should never have taken place to start with but the cheers are for the courage and resistance shown.

The geopolitical world is not a schoolyard and the world gang of bullies strike with much more deadly blows that fists.

By all accounts Venezuela has been under overt attack since 2014 by the U.S. hybrid war short of a military invasion. Other governments have been willing participants and accomplices by imposing their own share of threats and coercive measures (sanctions) against the Maduro government.

The latest set of “sanctions” imposed by Brussels on 11 Venezuelans has an additional peculiarity – some might say contradiction – of targeting individuals that are not aligned with Maduro or his governing United Socialist Party of Venezuela (Partido Socialista Unido de Venezuela-PSUV). For instance, Luis Parra was elected president of the National Assembly (AN) last January after being expelled from the Justice First party (Primero Justicia) headed by self-appointed “interim president” Juan Guaidó. AN first vice president Franklyn Duarte was elected for the Social Christian COPEI party. And Jose Gregorio Noriega, AN second vice president, was also expelled from the Justice First party and is in opposition to the ruling party.

What those individuals have in common is a willingness to be in dialogue and engage in democratic participation in the political life of Venezuela free of foreign interference. For that they are accused of being“Maduro-aligned” because President Nicolas Maduro has precisely the same goal. That is the real reason why they need to be punished by the EU as they were previously punished by Washington for their “actions undermining democracy”.

Nonetheless, the Council of the European Union while recognising Juan Guaidó, issued the following press release : “The Council today [June 29] added 11 leading Venezuelan officials to the list of those subject to restrictive measures, because of their role in acts and decisions undermining democracy and the rule of law in Venezuela.” To be noticed is the same language used by the U.S. “sanctions”.

To further contradict the argument of an “undemocratic” and “dictatorial” Maduro government is the fact that it is the monolithic political group headed by Juan Guaidó that does not seem to have a large representation of diverse ideological positions. Those who do not subscribe to its ruthless main goal of ousting Maduro from the presidency by any means are summarily expelled from the party, like in the case of Luis Parra and others.

President Maduro’s assertive reaction to boot out the EU ambassador was fully justified for at least two reasons.

Heightened awareness about independence. Most Venezuelans have a deep-rooted sense of anti-colonialism based on its 209 years of independence with long oppressive periods of being a U.S. “backyard”. One of the legacies of Chavismo has been a re-awakening of that sense of self-determination that is now imbedded in the cultural makeup of most Venezuelans.

This is in sharp contrast to the equally deep-rooted sense of colonialism that pervades policies of most European countries. Maduro made this point very explicitly when he protested the EU interference in Venezuela’s internal decision about the composition of the country’s National Electoral Council (CNE). Maduro said: “Don’t mess with Venezuela anymore. [Stay] away from Venezuela, European Union, enough of your colonialist point of view!” Foreign minister Jorge Arreaza concurred in a tweet, “[The EU] colonial heritage and reminiscence lead them through the abyss of illegality, aggression and persecution of our people.”

Intolerance towards any form of interference. The second reason related to the first one has to do with Venezuela’s intolerance towards any form of interference in the domestic affairs of the country. This is perhaps the biggest political gap between the Maduro administration that is nationalist and defender of sovereignty, and the Guaidó group that not only welcomes foreign intervention but actively invites it and is supported by it.

Venezuela abides quite fully to international law, especially to the United Nations Charter. No one can claim that Venezuela intervenes in the internal affairs of other countries. However, the U.S. blatantly circumvents international laws by issuing domestic executive orders or acts of congress that impose its extraterritorial self-appointed “right” on other nations. The numerous U.S. “sanctions” against Venezuela are enforced not only on U.S. entities but extraterritorially against non-U.S. entities often under use of threats. This is one of the most damaging form of interference aside from a military invasion. The EU and Canada are not too far behind in their interference approach.

It was equally justified that President Maduro would rescind his decision.

It has never been the intention of Chavismo and its Bolivarian Revolution to confront and reject fair, meaningful and respectful international relations. President Maduro has shown his resolve to that goal and, to his credit, has forced the EU to accept that resolve on this occasion. The joint comuniqué concludes, “The Ministry of Popular Power for Foreign Relations of the Bolivarian Republic of Venezuela and the Foreign Action Service of the European Union … agreed to promote diplomatic contacts between the parties at the highest level, in the framework of sincere cooperation and respect for international law.”

Perhaps Venezuelans should revel in the fact that President Maduro has also scored an important victory. The EU bloc of countries has recognised self-appointed Juan Guaido as “interim president” of Venezuela last January 2019. Nevertheless, this recent diplomatic tête-à-tête has forced Brussels to implicitly admit who the legitimate government of Venezuela is and to accept Caracas terms of negotiations.

It is not clear whether the EU will rescind the latest set of “sanctions”. But that will not stop the Bolivarian process to stand up to the bullies and continue its path to make colonialism obsolete.

The Pandemic Must Transform Our Agriculture

Moin Qazi

The COVID-19 crisis has highlighted the risks of an unhealthy diet and the extreme fragility of food systems. The economic reconstruction that will follow the pandemic is the perfect opportunity to provide better nutrition and health to all. The pandemic should spur us to redefine how we feed ourselves, and agricultural research can play a vital role in making our food systems more sustainable and resilient.

Family-owned farms still produce some 80% of the world’s food. There is an inextricable link between farmers with small landholdings and our survival and the health of our planet. They play a highly critical role in protecting the environment. But they are among the most underserved population.

They often lack the technology, infrastructure, and market access needed to increase their productivity and incomes. This makes them extremely vulnerable to economic and climactic variability.

In India about half of them live in the vast stretches of the Deccan and East Indian plateau, practicing rainfed farming due to lack of irrigation. Farming is therefore typically limited to monocropping, and is done only in the monsoon months.

Small farmers often lack basic tools and new technologies and don’t have networks to access them, the financial services to afford them, or the markets to profit from investments in them.

They are also plagued by low productivity as they do not have access to quality farm inputs such as good seeds and fertilisers, training and capital and technology and knowledge that can make their enterprises commercially viable.

Hence, they remain trapped in a cycle of low investment, poor productivity, low value-addition, weak market orientation and depressed margins, leading them to abandon farming and migrate from rural areas, often in conditions of great and slow distress.

According to National Sample Survey Office data, almost 70% of agricultural households have to spend more than they can earn, and more than half of all recognised farmers are in debt.

The Green Revolution started in the 1960s saw the widespread rollout of new agriculture technologies leading to a massive boost in crop production. But its focus on large-scale and water intensive farming came at great ecological cost. There were several bad consequences in the long term, such as:

- Massive loss of local agro biodiversity and associated traditional knowledge

- Alarming depletion of groundwater in most parts of the country,

- Undermining of seed sovereignty

- Increased dependence on credit to purchase proprietary seeds, insecticides and pesticides

- indebtedness on part of farmers due to low monetary returns from agriculture

- Damage to soil health and stagnation in productivity

- Low value of agricultural produce

- Toxic levels of pesticide residue in food

One of the cruel legacies of the Green Revolution has been the shift away from diversified agriculture to the dominance of cash crops such as cotton and sugarcane, and grains such as wheat and rice.

The Green Revolution brought in new strains of seeds generated through modern methods of plant breeding which gave high yields; intensified the use of fossil fuel fertilizers; increased acreage through double cropping; used pesticides and mechanical equipment extensively and massively; and drilled into groundwater reserves through deep borewells.

Native heirloom seeds adapted to local diets and conditions were replaced by expensive corporate-produced hybrids, often dumped in the country after having failed elsewhere.

Although the new high-performance varieties guaranteed high yields, they degraded soil quality, harmed biodiversity, polluted the environment and irreversibly damaged human health.

With water intensive agriculture came the problem of water-logging and soil salinity, increased incidence of micro-nutrient deficiencies (especially zinc) and soil toxicities (on account of iron released by chemical fertilisers), which slowed down yields and threatened the sustainability of food systems.

The large-scale cultivation of a single crop variety made it highly vulnerable to pests. These unwise farming policies have caused millions of farmers to lose their livelihoods, and hundreds of thousands to end their lives.

There has been a failure of agricultural strategy over the last decade. Food crops have gradually been abandoned in favour of cash crops which are more profitable but are also highly water-intensive.

The high yielding variety (HYV) seeds which entered Indian fields during the Green Revolution were less resistant to droughts and floods and needed delicate management of water, insecticides, pesticides and chemical fertilisers. Farmers found them highly sensitive to climate variations.

These crops also attract more pests forcing farmers to apply chemical pesticides to save them. So, every year the farmer had to spend more to grow such crops. Typically the commercial seeds had to be purchased year after year, and farmers could not reuse seeds from their crop, with seed manufacturing giants filing lawsuits against small farmers who did so.

It became a perpetual treadmill. Families faced crippling healthcare costs, crop failures, loss of income, and debt, all directly related to pesticides.

This method of agriculture is also irretrievably damaging biodiversity. The loss of biodiversity has its connection to another loss – that of indigenous cultures – in the ecosystems. From animals to insects and plants, the biodiversity loss is unprecedented and difficult to imagine; it also leaves us highly vulnerable.

The overuse of chemical fertilisers for augmenting yields in the short term led to physical and chemical degradation of the soil by altering the natural microflora and increasing soil salinity and alkalinity.

Higher yields and profits in the short term have come at a huge socio-ecological cost such as biodiversity loss, environmental pollution, land degradation, increased damage from climate change, decline in human health and livelihood, and the erosion of agricultural expertise.

Exposed to competition from highly subsidised agribusinesses in Europe and the USA, farmers were encouraged to breed a limited number of high yielding crops which would serve as cash machines. They found this switch to “modern industrial agriculture” would force them to buy commercial varieties of seeds, which often come with licence fees in perpetuity.

The peril of monoculture is something we have witnessed repeatedly in recent times. A bumper crop has usually been followed by a fall in prices. Alternatively, infection by pests can result in entire harvests being wiped out. Multi-cropping and crop diversification is beneficial just for humans, but also for the crops themselves.

Indigenous communities’ valuable knowledge of sustainable agricultural practices must be used such that these indigenous communities gain from it. Their knowledge covers all aspects of agriculture, from non-toxic biofertilisers and pest control methods to flood and groundwater management; from multi-cropping and seed preservation to food storage.

Experts are calling for a dramatic shift in the short-term profits approach to agriculture and advocating the use of traditional knowledge and time-honoured practices. Instead of industrial agriculture with misplaced technologies, they argue, farming should cooperate more closely with nature, with intelligent plant breeding and a return to old and proven crop varieties.

Formerly, societies might depend on 200 to 300 crops for food and health security, but gradually we have come to the stage of four or five important crops: wheat, corn, rice and soybean. This homogenisation increases profitability for a handful of owners, to the detriment of everyone else.

The cultivation of indigenous and heritage crops has the potential to make agriculture genetically diverse, sustainable and resilient to climate variability. Indigenous landraces have evolved in the region over thousands of years of agrarian practice and culture.

India is now seeing reverse engineering. There is now a growing emphasis on polyculture or planting a basket of crops, where multiple food grains such as millets, pulses and oilseeds are inter-cropped with other food crops. For instance, millet needs very little water, grows well in poor soil, grows fast and suffers from very few diseases. Once harvested it stores well for years.

Apart from enhancing soil fertility, multicropping provides multiple crops from the same piece of land. This maintains soil fertility, arrests soil erosion, and ensures the availability of different types of food in the household.

Crop rotation techniques ensure that no single botanical crop family has predominance in the rotation; hence pests are not able to thrive as they are usually specific to certain crop families. Apart from hedging the risks, crop rotation also allows the soil to be revitalised.

The use of diversified and eco-friendly farming that is nutrition-sensitive and climate-resilient is a better alternative to industrial agriculture. It is also less polluting and generates less farm waste, which is usually converted into animal feed and bio-compost by using organic additives, and can also be converted into energy.

Thus there is additional income and household nutritional security along with enrichment of biodiversity. Animal fodder is one of the important by-products of diversified agriculture.

Small farmers lack risk mitigation tools. A crop failure, an unexpected health expense or the marriage of a daughter are perilous events for these families. An adverse weather change, for example, can lead to a drastic decline in output and the farmer may not be able to recoup the costs of planting. Sometimes, farmers have to attempt to plant seeds several times because they may go to waste by delayed or excess rain.

Farmers in most middle-income countries need more capital than they can afford to generate through their savings. In fact, “developed” agriculture means capital-intensive agriculture.

Most farmers have been made to descend the socioeconomic ladder, where a farmer becomes a sharecropper, then a peasant without land, then an agricultural labourer, then is eventually forced into exile. These circumstances must be changed.

Small and marginal farmers are also denied access to institutional credit. Most of them depend on village traders, who are also moneylenders, to give them crop loans and pre-harvest consumption loans. Credit histories and collateral may serve to qualify middle-class customers for loans, but most rural smallholder farmers have neither.

The superior bargaining power of village traders and the middlemen means that the prices received by farmers are low. On account of the small size of the farms, they can rarely apply technological solutions that work best on a large scale. And with government extension workers not properly trained, small farmers do not have access to knowledge about best practices, for example, crop rotation techniques to help reduce pests.

Smallhold farmers need to practise smart agriculture like harvesting rainwater, using organic fertilisers and undertaking intercropping to protect these growers soil. They also need to revive some traditional farming practices that have been lost in the rush of new technology.

Several societies are now reviving the culture of seed mothers who are nurturing seed banks to curate indigenous varieties of seeds. Heirloom varieties, adapted over centuries to local ecologies, are sturdier and more adaptable in the face of problems such as pests and drought.

Another modern concept is natural farming, which is conceptually different from organic cultivation. The greatest modern evangelist of natural faming was the Japanese scientist and philosopher Masanobu Fukuoka, whose “do-nothing” farming is a minimalist approach that uses commonsense, sustainable practices that eliminate the use of ploughing, weeding, tillage, pruning, pesticides, fertiliser, external compost, chemicals and several wasteful efforts.

Its recent avatar is zero budget natural farming. ZBNF is a form of agricultural system redesign that reduces farmers’ direct costs while boosting yields and farm health through the use of non-synthetic inputs sourced locally. The aim is to return to a “pre-green revolution” style of farming that will put an end to unsustainable agricultural practices and help preserve India’s genetic wealth.

ZBNF involved the microbial coating of seeds using cow dung and urine-based formulations; application of a concoction made with cow dung, cow urine, jaggery, pulse flour, water, and soil to multiply soil microbes; mulching, or applying a layer of organic material to the soil surface, to prevent water evaporation and contribute to soil humus formation; and soil aeration through a favourable microclimate in the soil.

For insect and pest management, ZBNF propagates the use of various decoctions made from cow dung, cow urine, lilac, and green chillies. Farmers are able to produce more crops, more consistently – and all this without chemical fertilisers and pesticides or big demand on limited groundwater supplies.

To make farming sustainable and resilient, farmers must be encouraged to diversify into allied activities. They can be encouraged and financed to build ponds, bunds and set up horticulture farms

Secondary agriculture too should be promoted by public/private sector. Income- generation activities that use crop residues – paddy straw, fodder blocks and crop residue briquette- can supplement income from primary agriculture. The output from the farm should also be put to gainful use- either as fodder or for mulching. Cleaning, sorting and grading of agri-produce to make it saleable must also be promoted as supplementary enterprise.

When farming fails, livestock can serve as fall back. Tribal communities already keep backyard poultry, ducks goats, sheep Bee keeping, mushroom cultivation, backyard poultry, dairying and sheep rearing can be managed by women farmers in the-family. Unlike more valuable operations on farms in India—crops or cattle, for example—goats and sheep are managed almost exclusively by women. They bring them out for grazing, take care of them when they’re ill, and sell them at the market. And the most critical point is that the money women earn from their goats stays in their hands.

The villages are slowly building a cadre of goat nurses known as “pashu sakhis,” which means “friends of the animals”. Pashu sakhis are poor women themselves who are given basic training in how to vaccinate, deworm, and provide other preventive care to goats in their community.

Another important area is forest produce such as tasar silk which is a stable source of livelihood for many tribals The Forest Rights Act is an attractive law but it is very difficult for tribals to benefit from it on account of red tape and the reluctance of forest department to concede its control over forests. Steps should be taken to make the law more roadworthy.

Agro-processing needs medium-level entrepreneurs. It’s difficult for farmers with a hectare of land or 50 to 200 mango trees to set up an agro-processing unit. .entrepreneurs doesn’t want to go to small towns, rural areas, because of inadequate infrastructure, transport, electricity. No bank will finance them either.

Sustainable agriculture must build capacity to adapt to climate variability, so that farmers can conserve resources during years of good rainfall and harvests to adjust for years with poor production.

Climate variability has always been a challenge and is set to assume historic proportions. Larger-scale innovation to make staple crops more climate-resilient is essential for food security.

We need to understand crop-specific challenges and figure out farming models that can combine the best of high-tech and environmentally sound agricultural practices, bridging the gap between scientific know-how and farmers do-how.

It is important to harness all the tools that indigenous wisdom and contemporary science can offer. Only sincere cooperation between the two can ensure an agricultural revolution suited to our times.

A Look At The Past, Present And Future Of The China –Indian Border Dispute

Arka Deep

After five decades of status quo in their unresolved border issue, India and China have locked horns again, this time at Galwan Valley. With the first casualties in nearly 53 years, this face off is essentially becoming a cause for concern among people. While the BJP-led government is out to squeeze the last drop of publicity through their toxic ultra-nationalism, almost all of the national and regional parties have been unequivocal in condemning China’s actions. The criticisms have mainly complained about Modi’s lack of vigorous action by way of any response. But unless we are blinded by territorial nationalism, there will of course be the more skeptical readers who are ready to look at the problem before jumping to any conclusions. For them it is worth doing a brief review of the Indo-China border dispute and its origin. For convenience, we shall break up the article chronologically, so we can cover the issue from the Shimla convention of 1914 down to the Galwan face off of 2020. It is indeed hard to put in every piece of such a vast puzzle in the limited space of an article, but let’s try to find out some solutions, so we can take a more rational stand on the recent crisis.

How the Dispute Originated

The Border issue between India and China is as unresolved in the eastern sector as it is in the western, but in the light of recent developments we will try to focus on the western sector of the Line of Actual Control (LAC). In the contested area of the western sector lies a sparsely populated, rugged, and inhospitable mountainous terrain. While a number of treaties, notes and correspondences have transpired between the several parties (namely, the Ladakh-Tibet treaty of 1684, the Dogra-Tibet treaty, the Note of the British to the Chinese authorities in Tibet, correspondence between the governor of Hong Kong and the Chinese authorities in Canton, Britain’s Note to China in 1899, the Shimla convention, etc.), in most cases either there was no agreement or China refused to accept any treaty because of Independent Tibet representation (Shimla Convention).

To be specific, the question of any official border demarcation or delimitation never occurred to the local or Chinese authorities, as the territories were clearly separated by a vast tract of no-man’s-land. Until British strategic interests came into play (mostly vis-à-vis the advance of Russia’s empire), the arrangements were in fact quite simple and vague, unaccompanied by any detailed historical map. The first map which had any real precision, viz. the map of 1899, was nevertheless unilateral and never officially recognized by the Chinese government. If that map had to be followed, Aksai Chin would be partially incorporated into Britain’s possessions with the border running through the ridge of Lak Tsang, while the other half would be shown as a part of Tibet in accordance with Britain’s strategy of using Tibet as a buffer state between their sub-continental possessions and Russian expansion.

The interesting point is that this map was produced (mistakenly!) by the Indian government after 1947 to extend their claim over the whole of Aksai Chin (although the map transfers a significant share of territory into Chinese hands). The best summary of events that transpired during the British period would be to say, “the Sino-Indian Border was never officially delimited with the participation of the relevant parties”. The unilaterally demarcated borders were never based on the national interests of either China or India. They were based solely on the interests of British investment. In accordance with Britain’s perceptions, the perceived border waxed and waned over the decades. Apart from the point of Karakoram Pass where China placed a border demarcation in late 19th century, the other areas were never been settled, and this uncertain legacy was to be passed on to the successor states in India, Pakistan and China as a colonial residue after the departure of the colonialists.

Developments after 1949

Conditions after the end of empire were quite different. Instead of being a merely strategic issue for the former colonial power, it was now an issue of demarcating the extent of the national territories of two newly independent nations. A permanent solution of the border question was thus more necessary than ever before. A possible way out was to remove the contentious British legacy from the negotiating table and delimit the borders based purely on ground realities and historical connections. While China repeatedly stated that it regarded the Indo-Chinese boundary arrangements as invalid (they never accepted those), India was quite reluctant to open negotiations as it viewed the colonial maps as an acceptable representation of its national territory. Instead, Nehru’s government formulated the “Forward Policy” to contain the Chinese threat, following in the footsteps of India’s colonial masters. This decision would become a tremendous factor in future in leaving the Border issue unsolved. As the government of India refused to accept any negotiation on the question of further delimitation of boundaries (although these had never been delimited before), a series of events forced it into a border war, and no solution ever seemed to be easy again. Finally, from 1962 to date, the Line of Actual Control has been the de facto border between India and China. In the west, Aksai Chin remains a region under Chinese administration, while it is of course claimed by India as hers. In the eastern sector it is the reverse. But to be specific, these are mere claim lines, at best de facto boundaries, not officially delimited international borders.

The Question of Incursion and a Misguided Opposition

In a non-negotiated border, incursions are common phenomena. As different sides have their own logic and maps to show, what counts as an incursion in India’s view can easily be construed by the Chinese as China’s ‘patrolling of our own territory’. In recent times, unilateral decisions like the abrogation of article 370 and division of the state of Jammu and Kashmir into two union territories, coupled with the constant development of military infrastructure in a region of volatile multi-party dispute, can obviously make all neighbouring states anxious. If we add India’s current alignment with the Trump-led US government, the Chinese side is bound to react in one way or another. But our opposition parties also seem to have signally failed to understand the problem. Instead of pressurizing the government to go to the negotiating table and finally settle all outstanding issues, they are in war-mode. It turns out to be a cheap publicity stunt for the political establishment to sway public opinion in favor of violent confrontation, as India’s vast population has never actually seen the agony of war first-hand. This kind of misguided opposition in a time of crisis makes the situation even grimmer (the same happened in the 1960s, with the parties in reverse roles). In the end, the issue is simple. India and China have never officially delimited the boundary between their respective states. Hence, the only solution lies in a delimitation of boundaries, free from the ghosts of the colonial past and based on practical ground realities and mutual respect between the states. Though it seems to be a far cry at the moment to expect such a peaceful solution under the current regime that rules India (for ultra-nationalism is seen by this government as an asset), nevertheless that’s the only way forward to a peaceful future. It is up to us to decide between a peaceful, negotiated border and some utopian map in the geography books which is drawn with the blood of our people on it.

COVID-19: Infection Rate Per Million Population In Select Countries, Provinces And Countries – 4 July 2020

VT Padmanabhan

We have been seeing and hearing a lot of visual and print media news and statistics of the ongoing Covid-19 pandemic. This will continue for some time to come. Almost all reports give the absolute number of cases and deaths. As on 7 Jul 20, with nearly 3.1 million cases and 134,000 deaths the USA is on top, Brazil with 1.67 million cases is No 2 and India with 760,000 cases is No 3.

This is not the way we have been seeing other health or socio-economic data of different countries or region. The health data are normally presented as rates of birth, infant mortality, cancer death etc per thousand people. I could not figure out as to why international agencies like the WHO has departed from this historical practices. During the early days of the pandemic, WHO used to give the number of cases, deaths and recoveries and the total population of 31 provinces in Mainland China. Even this practice has been discontinued since.

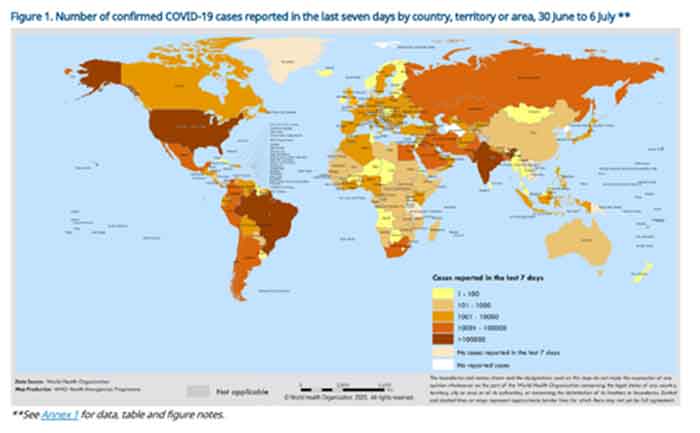

A map published by the WHO, showing three countries – US, Brazil and India with the highest number of cases, is reproduced below: Even though this is factually correct, it may have negative feelings among some viewers.

In this note I have calculated the rate of Covid-19 infection per one million population of the country or the region. Covid-19 has shown its presence 215 countries/regions in the UN system. The rate for China is 58 per Million and her position is 189th in the world. India has 506 per Million and her position is 114th.

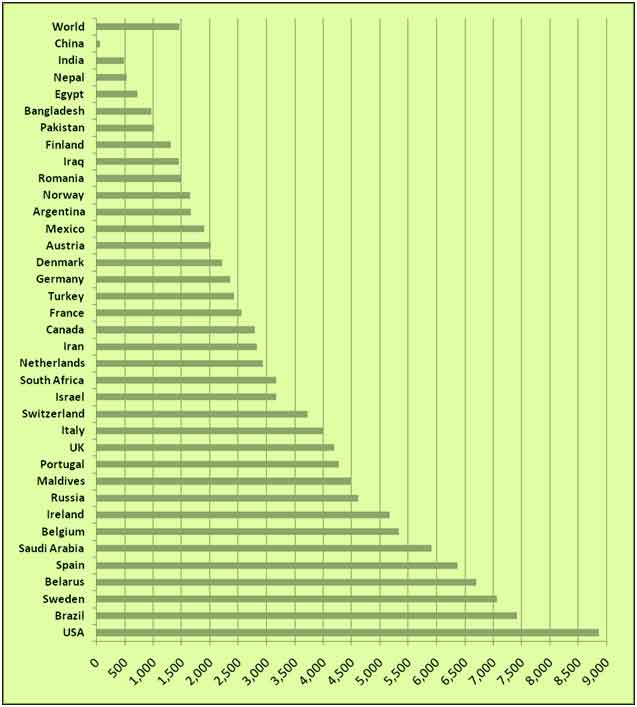

Graph 1: Covid-19 Cases in select countries as on 04 Jul 20 – Rate per million

Graph 1 shows the infection rate for 38 countries, which together have 65% of the world’s population and 88% of the Covid-19 infections. The rate given in per million population. Acutally, the US is not the No1 country as far infection rate is concerned. The US is the 6th country. The top slot is occupied by Qatar with a population of 2.8 million, 80% of whom guest workers, most of them living in crowded hostels. Qatar’s infection rate is 35,324 persons per million. The rates for other top countries are Bahrain – 16933, Chile – 15,266, Kuwait 11,544 and Peru 9070.

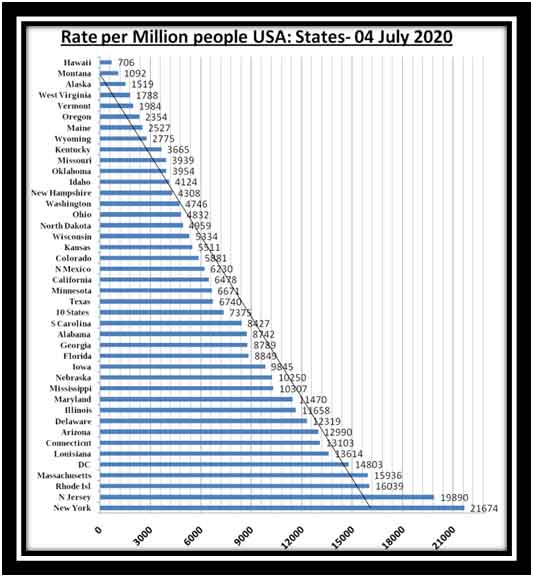

Graph 2; Rates per 1000 people in 51 US states are shown in Graph 2. Not all states in the US are equal. The rate for New York is 22,000 as against 2,000 per Million in Hawaii. 13 states with rates above 10/Million account for 41% and 18 States with rates between 5 -10 /per million have 51% of the total US Caseload.

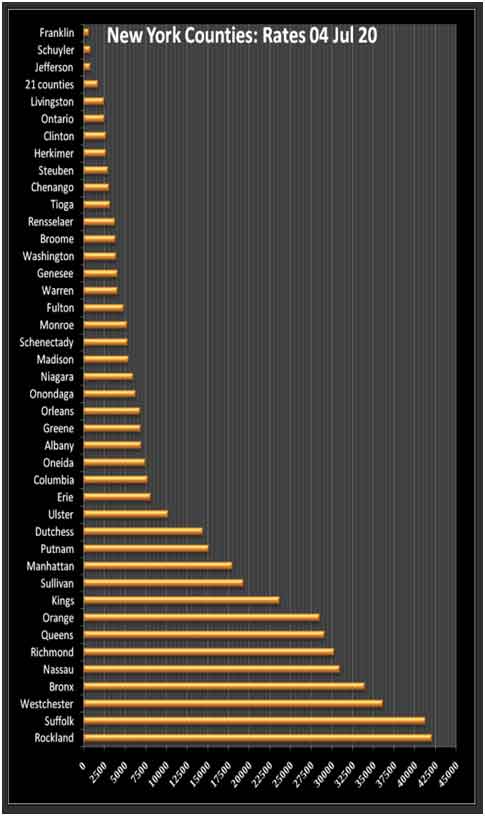

Graph 3 and 4: Rates in Counties of New York. All 62 counties in New York has Covid-19 cases. With 42 per thousand persons, Rockland is on top. With 0.7 per 1000, Franklin holds the lowest position. Graph 3 has data for counties with infection rate of 5000 and above and graph 4 has counties with rates below 5000 per million peoples

INDIA

The infection rate in India is 506 per million population. This rate is about 10 times that of China, which means India did not learn any lesson from there. Globally, India’s position is 114th.

The rate in US is 8,900. The average for the world is 1500 per million. State-wise, the National Capital Region (NCR) of Delhi with a total population of 18.7 million has the highest infection rate of 2671 per million. The Union Territory of Ladakh with a population of 290,000 has an attack rate of 2377 per million. Delhi and Ladakh are not shown in the Graph

About 70% of the cases in Maharashtra are in Mumbai metropolitan region. The infection rate in Dharavi, the biggest slum in Asia with an area of 6 sq km and a population of 650,000 is 3,555 which is less than a tenth of the rate in Qatar. As of now, the Dharavi cluster is under control. According to The Hindu, the success can be attributed to effective containment strategy, conducting comprehensive testing and ensuring uninterrupted supply of goods and essential supplies to the community.

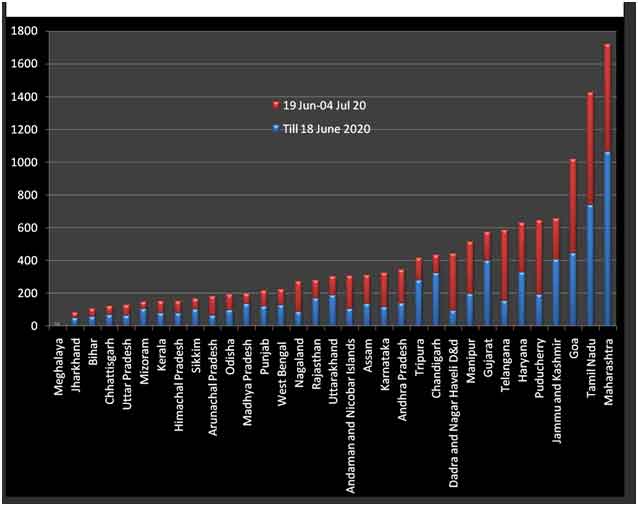

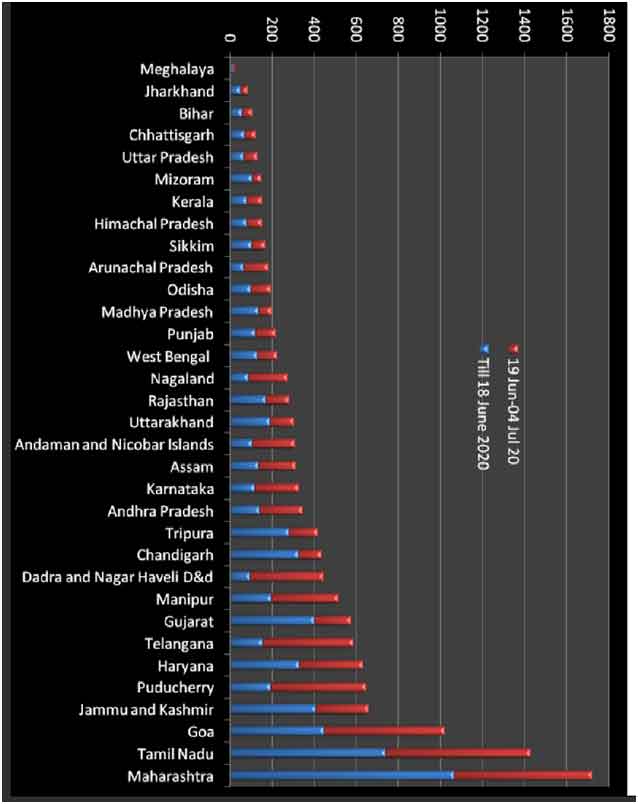

INDIA – RATES PER MILLION BY STATES AND UTs AS ON 18 JUN 20 AND 04 JULY 20

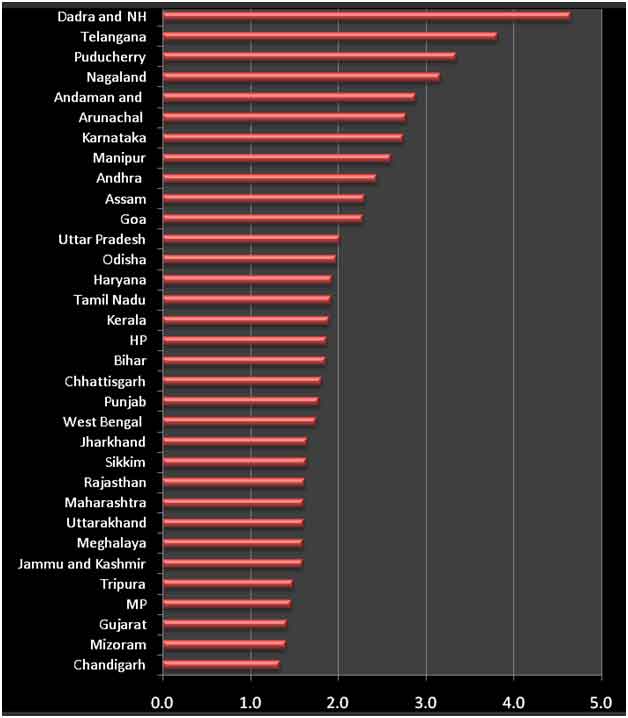

COVID -19 IN INDIA – INCREASE IN INFECTION RATE BETWEEN 18 June 04 JUL 2020

Graph 6 gives the trajectory of the pandemic in India during 18 June to 04 July 2020. The growth rate ranged from 3.8 in Telangana to 1.3 in Chandigarh.

The infection rate in counties like Richmond and Suffolk in New York State is above 40,000 per million. In comparison to that, rate in Dharavi in Mumbai, is less than a tenth. An expert had earlier theorized about some inherent stuff in India, which prevents the spread of the disease. We have to remember that there were only 1255 cases on 30 March 2020. After about 100 days we have now more than 700,000 people, an increase of more than 500 times.

The lower rates in most of India, other than big cities, means that we are in a relatively safer zone. The tragedy unfolding in high infection rate places like Chennai, Delhi and Mumbai should make us more vigilant.

The vaccine and drug industry is putting all their might to save the world from the pandemic. Of this vaccine group is the most active. For decades, they have not invent a vaccine, though there have been several viral epidemics. If the disease is contained at the earlier stage, as the Chinese did it, there is no scope for vaccine research and sales. China and India are also in the vaccine trail. If these two succeed, the chances of getting a vaccine which is affordable for majority of the people are brighter.

The USA is not seriously thinking about bringing the epidemic under control. The talk is generally centred around getting a vaccine by the year end. India and several other countries in the world do not have to wait for the magic bullet. Because it may not arrive as the scientist know very little about this virus. As the virus is going to be with us for a long time, we have to embrance the simplest preventive measures -the face mask, social distance and hand hygiene.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)