Richard Wolff

Near the end of his life Lenin gave a speech that referred to the USSR as a transitional society. He explained that socialists had taken state power and could thereby take the post-revolutionary economy—which he labeled “state capitalism”—further. The socialists’ state could achieve transition to a genuinely post-capitalist economy. He never spelled out exactly what that meant, but he clearly saw that transition as the revolution’s goal. In any event, conditions inside and outside the USSR effectively halted further transition. Stalin’s USSR came to define socialism as state power in socialists’ hands overseeing an economy that mixed private and state enterprises with market and state planning mechanisms of distribution. The state capitalism originally conceived as a transitional stage en route to a socialism different from and beyond state capitalism came instead to define socialism. The transition had become the end.*

The “different from and beyond” faded into a vague goal located in a distant future. It was a “communism” described by slogans such as “from each according to his ability, to each according to his need.” It named a party with communism as its goal, but socialism as its present reality.

The hallmark of capitalism, what distinguished it from feudalism (lord/serf) and slavery (master/slave), was the employer/employee relationship structuring its enterprises. In Stalin’s USSR and since, the employer/employee relationship became, instead, a necessary, unquestioned presumption common to any and all “modern” economies, capitalist and socialist alike (rather like machinery or raw materials). That Stalinist view of the universality of the employer/employee relationship was also the view of all major strains of economic thought in the capitalist world outside the USSR.

China’s Communist Party largely replicated the USSR’s history in terms of constructing a state capitalism overseen by the party and the government it controls. One key difference from the USSR has been China’s ability to engage with the world market in ways and to degrees the USSR never could. China also allowed a far larger component of private enterprises, foreign and domestic, alongside state-owned and operated enterprises than the USSR did. Yet China today, like the USSR a century ago, faces the same transition problem: transition to a post-capitalist society has been stalled.

In China since at least the 1970s, the Communist Party and the government it controls have managed state-owned and supervised private enterprises. Both kinds of enterprise exhibited the same employer/employee structure. Chinese state capitalism is a hierarchy with the party and government at the top, state and private employers below them, and the mass of employees comprising the bottom. Western private capitalism has a slightly different hierarchy: private employers at the top, parties and government below them, and the mass of employees comprise the bottom.

China’s economy has grown or “developed” much faster over recent decades and now rivals the United States and EU economies. China was better prepared for and better contained the damages flowing from the 2000 dot-com crisis, the 2008-09 Great Recession, and the 2020 COVID-19 crisis. The party and government in China mobilized private and public resources to focus on prioritized social problems that also included reduced dependence on exports and massive infrastructural expansion.

China’s party and government have produced a huge, well-educated labor force working for private and state enterprises, foreign and domestic. Popular support for China’s existing economic system seems widespread notwithstanding considerable criticism and some opposition. Rising labor productivity yielded rising average real wages (also rising far faster than in the West). Across these years, no Chinese troops fought in any foreign wars. Housing, education, health care, and transportation received massive investments; their supplies often grew ahead of Chinese demand for them.

A key lesson of Chinese development is that economic objectives are better met faster if a dominant social agency prioritizes achieving them and can mobilize the maximum resources, private as well as public, to that end. China’s party and government were that agency.

In Western capitalism, no comparably empowered social agency possessed that power. Private and public sectors stayed separate. Ideology and politics generally kept the public subordinate to the private. The private employers’ differing particular interests and profit-driven goals discouraged many kinds of coordinated behavior among them as did their system’s structures of competition. Party and state apparatuses depended on corporate donations and corporate media supports. Thus, in Western capitalism, no social agency played the national resource-mobilizing role that the party and government played in China.

Some Western capitalist countries embraced social democracy (as in much of western Europe). There states provided major social supports (national health insurance, subsidized schools, transport, housing, etc.) that enabled some state-mobilized national resources for social priorities. The less capitalist countries embraced social democracy—the more committed to laissez-faire ideology and private-sector dominance—the less they could mobilize national resources. The United States and UK are prime examples of such countries; hence their poor preparations for and containments of the COVID-19 pandemic and the capitalist crash of 2020.

A second lesson China offers the world concerns the relationship between the basic structure its private and public enterprises share and the nature of its socialism. Almost all enterprises in China have an employer/employee internal structure; they differ in who the employers are. In state owned and operated enterprises, state officials occupy the employer position. In private enterprises, the employers are private citizens; they occupy no position within the state apparatus.

China’s economic system differs sharply from a Western capitalist system. First, it has a larger sector of state owned and operated enterprises than what Western capitalisms display. Second, it accords a dominant political and social role to the party and government. The latter together direct the economy’s development and coordinate how economy, politics and culture interact to achieve its goals.

China’s economic system is also clearly not a communism in the sense of having overcome the employer/employee structure or mode of production. To the extent that such overcoming once occurred during the era of communes early in the history of the People’s Republic of China, it mostly vanished. Employer/employee structures of enterprises are today’s Chinese norm. China is not post-capitalist. China is, as the USSR was, socialist in the sense of a state capitalism whose further transition to post-capitalism has been blocked.

There is an alternative way of drawing a second lesson from China’s remarkable history over the last half-century. We could infer that by socialism with Chinese characteristics, China means its system of a socially dominant party and state directing a mix of private and state-owned enterprises, both organized in the typically capitalist structure of employer and employee. Western European “socialisms” (Scandinavia, Germany, Italy, etc.) would thus also, like China, fall somewhere in the blocked transition from capitalism to post-capitalism. Despite Europe’s different politics and multiple-party system, most of its parties accept and reinforce a commitment to a kind of state capitalism.

The socialisms of the USSR, China, and western Europe were and are transitional. They all embody a process that got stopped or stalled en route to a post-capitalist society barely imagined. “Actually existing socialisms” were actually state capitalisms ruled, more or less, by persons and associations who wanted to go somewhere further, beyond, to a society much more different from capitalism. Hence the gap felt deeply by so many socialists and socialist organizations (parties, etc.) between what motivates their commitment (socialist ideals) and what they can and must do in their practical lives.

The Cold War waged against the USSR added to the pressures that blocked transition from going beyond state capitalism. A cold war now against China will do the same. Even without cold wars, internal pressures in the USSR and China likely sufficed then and suffice now to stall any transition beyond state capitalism. And so it is as well with western European-type socialisms. The only way the transition can be resumed would be if some force within the private and/or state capitalisms emerged that defined its project as precisely that resumption.

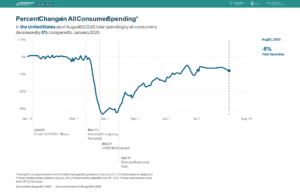

Global capitalism today exhibits historic difficulties: pandemic closures, global depressions (in 2008 and worse in 2020), extreme and deepening inequalities within nations, unsustainable government, corporate and household debts, and collapsing coordination among blocs (the United States, China, the EU, Brazil, Russia, India, China and South Africa, etc.). Long-deferred social problems (global warming, racism, labor migration, and gender inequality) are exploding as partial effects and partial further causes of those difficulties. Everywhere social movements are emerging or struggling to emerge in response to the difficulties and problems besieging modern societies.

All those movements share the problem of defining just what they will do to solve the problems motivating them. Many will yet again see government as the solution. Their program will give the state more power to oversee, regulate, control, and spend for the solution. Those people may or may not label their views as “socialism.” Either way, their proposals advocate for or sustain another blocked transition: from a private to a state capitalism or from a lesser to a greater degree of state capitalism.

Over the last century, many attracted to socialism have come to understand that blocked transitions did not and do not suffice to solve the problems created by modern capitalism. Those people can now become the new social force to unblock the socialist transition. From below, they can demand an end to the employer/employee structure of enterprises, public as well as private.

That end would help define the new society to which an unblocked socialist transition can and must now proceed. That society would be post-capitalist: different from and beyond all actually existing socialisms. It will have displaced the employer/employee structure of enterprises in favor of the democratic, worker cooperative structure.

In the late 18th century, the French and American Revolutions marked the transition from feudalism to capitalism. Leaders of those revolutions believed that they would bring into being a new society characterized by liberty, equality, fraternity, and democracy. But that transition also stalled: it did achieve the change from lord/serf to employer/employee, but it did not achieve the further changes to that desired new society. Socialism mostly represented the continuation of the drive toward those further changes.

But the socialisms of the USSR, China and western Europe stalled too. Their advocates and leaders had believed that a transition from private to state capitalism would bring those further changes that capitalism never did. The lessons of Soviet and Chinese socialisms offer a profound critique of stalled socialism, their own and others’. The completion of the passage from capitalism and beyond socialism as a transitional stage requires a micro-level economic revolution. The dichotomous employer/employee relationship inside enterprises must give way to a democratically organized community of workers who collectively employ themselves as well as direct the enterprise. That economic foundation—what communism concretely means—offers us a better chance to realize the goals of liberty, equality, fraternity, and democracy than capitalism or socialism ever could.