John Vassilopoulos

Since June 1, eviction proceedings have begun by Greek authorities against over 11,000 refugees, whose asylum claim was approved prior to May this year.

The move is being enforced by legislation of the New Democracy (ND) conservative government that came into force this March. It stipulates that once an asylum claim has been approved refugees have 30 days to leave the camps, apartments and hotels that they are being housed. Any welfare benefits they were eligible for as asylum seekers is cut off.

All 67 hotels operating as asylum seekers’ hosting facilities in the country will close by the end of the year.

The actions of the ND government are particularly brutal as the evictions are underway amid a resurgence of the COVID-19 pandemic, with hundreds of new infections announced each day.

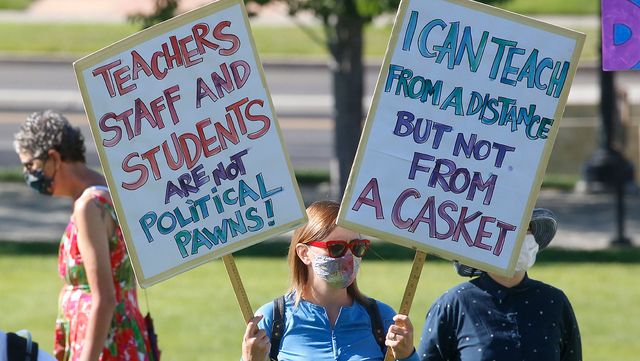

Afghan migrants camp with their families, following their arrival from Lesbos' Moria camp. (AP Photo/Yorgos Karahalis)

Afghan migrants camp with their families, following their arrival from Lesbos' Moria camp. (AP Photo/Yorgos Karahalis)

The measures are being sanctioned under an amendment added to the so-called “International Protection Act” (IPA), which was passed by the Greek parliament in late 2019 and came into force at the start of this year. The punitive legislation is a gamut of punitive measures, which include a new expedited asylum claim process that severely erode the right to claim asylum formally protected by international law. The new process is being applied as a priority to those that have arrived since the start of this year, with many claims being processed within days of arrival. The law allows for claims to be rejected as a result of minor administrative infractions, including not attending a claim interview or not renewing registration on time.

The legislation enshrines into law the hostile environment refugees already face in Greece in order to deter others from coming. That much was made clear by Migration and Asylum Minister, Notis Mitarakis, in an interview to Skai TV in early March when he stated: “Our aim is to give asylum within two to three months to those that are entitled and thereafter to withdraw benefits and accommodation because all of that attracted people to come to our country and take advantage of these benefits.”

The process of evictions, which was delayed for a few months while Greece was in lockdown, has caused visible scenes of destitution with hundreds of refugees—many of them families—sleeping in Victoria Square in the centre of Athens. An article published in Vice on August 21 reported that, “Newborn babies and disabled elderly are among those camping on mats and cardboard boxes, exposed to blistering heat and without regular food or water.”

A report published on August 3 by Refugee Support Aegean (RSA) documented the cases of several vulnerable families who were recently evicted from the notorious Moria camp on the island of Lesbos, only to find themselves homeless in Victoria Square.

It cited the case of Abdul, a torture survivor from Afghanistan and father of an autistic child: “My child’s condition is very serious. He cannot be in noisy places, under stress. Any extra tension worsens his psychology and health. Since we [found ourselves] in the streets of Athens, he seems to [suffer from] severe headaches. He holds his head often; he presses it and he beats it. Our biggest problem is that we have no home, no safe place, no protection… We are ill, and we are getting more ill. We are stressed out and we get more stressed out. I feel a deep fear inside me….”

Human Rights Watch cited the case of Basira, “a 21-year-old woman from Afghanistan who is alone in Greece.” This month she was given just days to leave her tent in the Moria camp after being granted asylum. Basira said, “They cut the cash assistance and told me I have to go… They said that if they come again and find me [in the tent] they will take me by force. I felt fear and despair because I am on my own, I didn’t know where to go.”

Migration and Asylum Minister Mitarakis provocatively attempted to shift the blame onto refugees themselves by tweeting οn July 3: “This year, 16,000 migrants left from our islands, unfortunately 110 individuals are in Victoria square. There is a support programme for finding housing and work, they must ‘stand on their feet,’ we cannot give them privileges for life.”

A written submission on behalf of the RSA this June to the European Court of Human Rights gives the lie to Mitarakis’ assertions by highlighting the Kafkaesque maze confronting refugees seeking to “stand on their feet.” It stated: “Status holders in Greece continue to face specific challenges posed by severe administrative barriers to access to different types of official documentation. These obstacles prevent people from fulfilling the necessary documentation prerequisites for accessing key rights such as health care, housing, social welfare and access to the labour market under equal conditions to nationals.” A case in point is the Tax Identification Number (AFM), whose issuance requires proof of address. However, this places those recently evicted in a Catch-22 situation, since the AFM is also required in renting a property in the first place as well as opening a bank account.

The new legislation has been accompanied by an intensification of so-called “push-backs” by the Greek Coast Guard, which involves forcing boatloads of refugees and migrants back across Greece’s sea border, a practice which is illegal under international law.

According to an investigative report published by the New York Times August 14, at least 31 separate such incidents involving at least 1,072 asylum seekers have taken place since March. According to the report “migrants have been forced onto sometimes leaky life rafts and left to drift at the border between Turkish and Greek waters, while others have been left to drift in their own boats after Greek officials disabled their engines.”

The article cited the testimony of Najma al-Khatib, a 50-year-old Syrian teacher, who says masked Greek officials took her and 22 others, including two babies, under cover of darkness from a detention centre on the island of Rhodes on July 26 and abandoned them in a rudderless, motorless life raft before they were rescued by the Turkish Coast Guard.

Najma al-Khatib, a 50-year-old Syrian teacher who survived one of these incidents, told the NYT, “I left Syria for fear of bombing—but when this happened, I wished I’d died under a bomb.”

Responding to the New York Times report, Ylva Johansson, who oversees migration policy at the European Commission expressed “concern” but stated she was “powerless to investigate their validity.” She added, “We cannot protect our European border by violating European values and by breaching people’s rights. Border control can and must go hand in hand with respect for fundamental rights.”

Such empty rhetoric belies the fact that Greece’s policy is part of the EU’s wider strategic goals.

Johansson herself flew to Greece in March together with the European Commission’s Director-General for Migration and Home Affairs, Monique Pariat, where they held meetings with Mitsotakis and Mitarakis. According to an announcement by the Commission, the visit was “in continuation of the support measures announced last week on the management of the migration crisis in Greece.”

Towards the end of June, in a letter to Mitarakis, Pariat praised “the progress made by migration and asylum authorities under the guidance of Mr Mitarakis,” adding that his efforts “are not just important for Greece and for the EU.”

More ominously, the EU border patrol agency, Frontex, has pledged to increase its forces in the Aegean. At the beginning of March just as Greece was stepping up its push-back operations Frontex Executive Director Fabrice Leggeri stated: “Given the quickly developing situation at the Greek external borders with Turkey, my decision is to accept to launch the rapid border intervention requested by Greece. It is part of the Frontex mandate to assist a Member State confronted with an exceptional situation, requesting urgent support with officers and equipment from all EU Member States and Schengen Associated Countries.

“Starting next year we will be able to rely on the first 700 officers from the European Border and Coast Guard standing corps to provide operational flexibility in case of a rapid border intervention.” He complained, “Today, we depend entirely on EU Member States and Schengen Associated Countries for contributions to come through at this crucial time.”

Evelien van Roemburg, the director of Oxfam’s migration campaign in Europe, noted, “The European Union is complicit in this abuse, because for years it has been using Greece as a test ground for new migration policies. We are extremely worried that the EU will now use Greece’s asylum system as a blueprint for Europe's upcoming asylum reform.”

The pseudo-left opposition, Syriza (Coalition of the Radical Left), is attempting to portray ND’s measures as inhumane and its own period in office from 2015-19 as one which saw the harmonious integration into society of immigrants and asylum seekers.

What a fraud! Greece was turned into Europe’s border guard and jailer under Alexis Tsipras’s government, as part of a dirty deal Greece agreed with the EU and Turkey. As the WSWS noted, in its series on Syriza’s reactionary legacy, the deal “lifted the basic right to asylum and was deemed illegal by several human rights organizations as well as the United Nations. Since then, incarcerated in the overcrowded hotspots, thousands of refugees have spent years in catastrophic conditions. Two months after the deal the Syriza government employed tear gas and stun grenades against protesting refugees in Idomeni and ordered the clearing of the camp.”