Josh Varlin

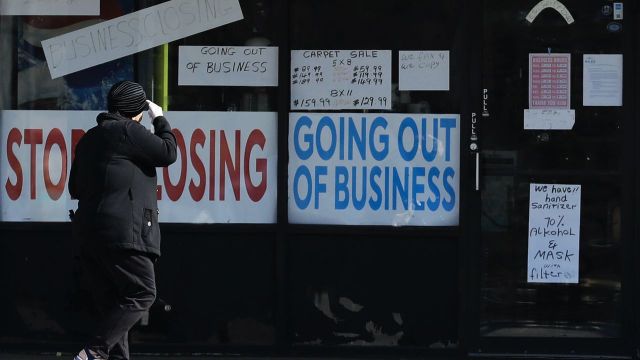

New York City was the global epicenter of the COVID-19 pandemic for several weeks in March and April, during which time tens of thousands of people were infected and thousands perished. Recent studies and reports have revealed more fully the role economic inequality has played in determining the virus’s toll, particularly in “disparities in hospital care,” as a July article in the New York Times describes.

Over and above the many other factors contributing to the high infection rate and death toll in New York City (the largest of which being the weeks-long delay in shutting down nonessential businesses), the simple fact that people received different standards of care at different health care facilities—determined largely by their class—often determined whether someone would live or die once they got sick.

This is contrary to Governor Andrew Cuomo’s April 7 claim: “I don’t believe we’ve lost a single person because we couldn’t provide care. People we lost we couldn’t save despite our best efforts.”

In fact, as the New York Times report as well as other interviews with health care workers demonstrate, people did indeed die for lack of care. Had the health care system in New York City been better resourced, many fewer people would have died in emergency room waiting areas before they were seen, alone in understaffed hospital wings or asphyxiating on hospital bathroom floors.

Overall, nearly 24,000 people have been killed by COVID-19 in New York City, according to city data on confirmed and probable deaths. About two-thirds of those who have lost their lives due to COVID-19 “lived in ZIP codes with median household incomes below the city median,” according to a Times analysis of city data.

Death rates per capita in the working class “outer boroughs” were larger than in Manhattan in every age group of adults, with the Bronx suffering the highest rates (2,239 of every 100,000 people over 75 died in the Bronx, a staggering figure) followed by Queens and Brooklyn, which were essentially tied. Staten Island also had higher death rates than Manhattan.

Within Manhattan, deaths were disproportionately in the poorer neighborhoods in the northern part of the borough, rather than in wealthier neighborhoods like the Upper West Side, which saw many of its residents decamp to summer homes in March and April.

With a second wave in New York City all but inevitable if schools reopen later this month—an open question given the immense opposition among educators—an understanding of how the pandemic unfolded in its first wave is necessary.

Before proceeding further into how disparities in care affected patient mortality, it is necessary to review the conditions leading to the high number of infections in the first place.

How the virus spread

New York City is the largest city in the US, with 8.3 million residents and some 20 million in its metropolitan area. In addition to being the home of Wall Street and global finance, it is an international center of culture and travel.

New York is also one of the most unequal cities on the planet, with the most millionaires of any city in the country along with millions living in or near poverty only a short subway ride away from each other.

All of these factors, along with the largest public school system in the country, educating over a million children, and a public transit system used by millions every day, created perfect conditions for the virus to spread rampantly, especially given the fact that basic public health measures were delayed for weeks—which alone killed tens of thousands, including in areas the virus spread to from New York City.

A preprint study from Columbia University researchers concluded that 55 percent of deaths from March 15 to May 3 could have been prevented had lockdown measures been implemented one or two weeks earlier than they actually began, starting in mid-March. New York City was the global epicenter for much of this period.

There is already some popular understanding of how the coronavirus infected workers and the poor disproportionately. The pandemic tore through working class neighborhoods in the Bronx and Queens in particular. Neighborhoods with large immigrant populations, like Queens’ Elmhurst and Corona, were severely affected.

Many factors played a hand in this: high poverty rates, dense and often multigenerational housing, many people working in low-wage jobs that can only be done in person and are considered “essential,” and reluctance to seek medical help due to a lack of insurance. Add to this the high percentage of immigrants in these neighborhoods—many of whom are afraid to seek services due to fear of deportation—and it is clear that this situation presented a “perfect storm” of susceptibility of infection.

It should be stressed that, while the conditions in New York City’s working-class neighborhoods were Petri dishes for the coronavirus, its rampant spread was only made possible by systematic public health failures at the municipal, state and federal levels. Mayor Bill de Blasio and Governor Cuomo, both Democrats, were united with President Donald Trump, a Republican, in initially downplaying the pandemic and delaying public health measures.

Indeed, the Financial Times has reported that Jared Kushner, Trump’s son-in-law and a top adviser, discouraged testing in the early stages of the pandemic to avoid spooking the markets. This resulted in a situation where the early spread of the pandemic was totally missed in New York City, and even in March confirmed cases were underestimations by a factor of at least 100 of the true spread of the disease.

How the virus killed

There are many factors contributing to the large number of people who have died from COVID-19, beginning with the disease’s basic features. It attacks the respiratory system and prompts a severe immune system reaction called a “cytokine storm,” which wreaks havoc on the patient’s lungs. However, the disease also impacts other organs and inflames blood vessels in ways that are only beginning to be understood.

COVID-19 is particularly deadly to elderly patients, as well as those with preexisting conditions such as obesity, hypertension and diabetes. However, young patients in their 20s and 30s have suffered strokes and died due to the disease as well, and even very young children have perished.

Just as the illness increases the danger of and reveals preexisting individual health conditions, so does the pandemic itself highlight preexisting social conditions, particularly inequality and all that comes with it.

In the first place, those with lower incomes are more likely to have preexisting conditions making them more likely to die from the disease, including hypertension, obesity and diabetes, all of which are often caused by lifestyle and dietary issues exacerbated by poverty.

An investigation in the Journal of the American Medical Association found that COVID-19 patients hospitalized in March and early April at Northwell Health facilities in the New York City area very often had comorbidities: 56.6 percent had hypertension, 41.7 percent were obese and 33.8 percent had diabetes. Hypertension and diabetes were thus much more prevalent among those who needed hospitalization due to COVID-19 than among the population at large, while obesity has been found to adversely affect patient outcomes.

However, even these social factors, as important as they are, do not paint the full picture. The quality of care received—and, consequently, whether a patient lived or died—often came down to which hospital received the patient, or, in other words, where the patient lived.

Inequality of care and COVID-19 mortality

As thousands were languishing in overcrowded and understaffed hospitals in March and April, patients in well-resourced private hospitals received much better care and suffered a lower death rate, even when considering factors like comorbidities.

The New York Times found that, in April, “patients at some community hospitals were three times more likely to die as patients at medical centers in the wealthiest parts of the city.”

Inequality of care, particularly in patient-to-staff ratios, is at the root of this disparity. A nurse at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell Medical Center explained to the World Socialist Web Site:

The link between nurse staffing ratios and patient safety is well-researched, measured by increased rates of morbidity, fall incidents, medication errors, overall patient satisfaction and other adverse events. It’s logical that assigning increasing numbers of patients will eventually compromise a nurse’s ability to provide safe care and stay vigilant. I’ve worked in a smaller hospital in Queens that consistently pushed us to 1:8 ratio on a medical-surgical unit, whereas NYP/Cornell doesn’t typically go above 1:5; 1:6 is the absolute max. There’s always been a difference in quality of nursing care between these two hospitals; the pandemic has simply exacerbated it. Breakdowns in the quality of care are often due to staff fatigue. For example, nurses may cut corners with PPE protocol under stress. I’ve also seen housekeepers improperly cleaning COVID rooms because they are understaffed and exhausted.

The WSWS has previously noted in relation to a planned strike at the University of Illinois Hospital that “[t]he odds of a patient dying increased by 7 percent for every additional patient a nurse had to take on.”

Indeed, a study by Karen Lasater of the University of Pennsylvania School of Nursing found that “each additional patient per nurse was associated with significant increases in the odds of nurses reporting poor outcomes,” including burnout, poor patient safety, work interruptions and nurses not recommending their own hospitals.

The most glaring examples of inequality were between the wealthy private hospital systems on the one side—which treat mostly insured patients and have substantial endowments—and small independent hospitals and the public hospital system, New York City Health + Hospitals—which treat many uninsured patients, or those on public insurance—on the other.

Health care workers told the New York Times that the patient-to-staff ratio in emergency rooms “hit 23 to 1 at Queens Hospital Center and 15 to 1 at Jacobi Medical Center in the Bronx, both public hospitals, and 20 to 1 at Kingsbrook Jewish Medical Center, an independent facility in Brooklyn.” The recommended maximum is four patients per nurse.

Indeed, staff distribution in the health care system was so irrational that by the end of April, with many hospitals inundated and in need of assistance, some hospitals had the problem of over staffing.

Victoria Gregg, a traveling nurse from North Dakota who worked at the smaller non-profit St. Barnabas Hospital in the Bronx from April 23 to June 11, told the Bismarck Tribune that a nurse from a wealthy part of the city asked if Gregg’s hospital was experiencing overstaffing, which had been a problem at that nurse’s hospital.

Other glaring inequalities abounded during the height of the pandemic: access to experimental drugs, access to ventilators with proper settings, sufficient dialysis machines and access to advanced treatments. All of these factors, combined with the aforementioned public health factors, combined into significantly higher death rates for working class patients.

For example, the mortality rate for COVID-19 patients at Bellevue Hospital Center, a public hospital in Manhattan, was double the rate at New York University Langone Health’s flagship a mere 1,000 feet away.

One of the most disturbing phenomena at understaffed hospitals was what Dr. Dawn Maldonado, a resident doctor at Elmhurst Hospital, termed “bathroom codes.” Dr. Maldonado relayed to the Times that multiple patients would remove their oxygen masks to go to the bathroom and then collapse.

In April, a nurse at Elmhurst told the WSWS that the patient-to-nurse ratio in her unit had doubled from six patients per nurse to 11 or 12. “A single nurse is doing the work of two nurses,” she said. This was under conditions where she had not received full training as a critical care nurse and where nurses in March “had very limited supplies” and had just begun receiving masks at the time of the interview.

Inequality also killed patients within the same hospital systems, including NewYork-Presbyterian and NYU Langone. Workers in both systems wrote letters warning about disparities in care leading to people dying unnecessarily because they ended up at a poorer-resourced hospital within that particular private network.

While networks have denied that inequality resulted in different access to care, some of them reallocated resources and staff after internal staff protests, but only weeks into the pandemic and after much damage had been done.

For example, at the private Mount Sinai network, 17 percent of patients at its Manhattan flagship died, whereas 33 and 34 percent died at its Queens and Brooklyn facilities, respectively. A staggering 41 percent of admitted COVID-19 patients died at Coney Island Hospital, a public hospital in the same network as Bellevue with its 22 percent mortality rate.

It should be noted that even wealthier hospitals still had to make what have euphemistically been called “crisis” decisions, such as rationing personal protective equipment (PPE) such as N95 masks.

The NewYork-Presbyterian nurse told the WSWS: “PPE was scarce and aggressively rationed. … [M]y coworkers and I have saved all of our N95s and keep 20+ used ones in each of our lockers in case NYP can’t provide to us in the future.”

Even under conditions where Weill Cornell did not run out of masks (having rationed them aggressively), its PPE policies produced irrational side effects, like having “to treat each PPE item differently rather than just disposing everything, which would arguably be easier (i.e., saving N95s and sanitizing face shields, but discarding outer surgical masks, hair covers and shoe covers, while sanitizing your hands between every step) in a particular order.”

At the same time, the nurse-to-patient ratio in the intensive care unit (ICU) doubled from 1:2 to 1:4 during the pandemic, with nurses training each other for other positions rapidly in order to increase capacity by 50 percent. “So there were a lot of unprepared nurses in roles they weren't familiar with,” the nurse told the WSWS.

This was the situation at NewYork-Presbyterian/Weill Cornell, which, she said, “is considered one of the most well-financed and well-resourced hospitals in New York, and I believe our staff and patients directly benefited from this privilege.”

In contrast, at NewYork-Presbyterian Queens, the nurse-to-patient ratio in the ICU quadrupled, meaning each nurse was dealing with up to eight patients requiring constant attention and monitoring.

A central remedy to overcome the disparity in staff and other resources, transferring patients, was only implemented belatedly. In late March, even as Elmhurst Hospital was inundated with patients, stretching workers there past their breaking point, nearby hospitals had excess capacity.

In the early period of the first wave, state officials left the public and private networks, which compete with each other, to their own devices, only intervening to facilitate patient transfers after reports and videos emerged from Elmhurst Hospital revealing the dire conditions there. Much like the belated lockdowns, this action saved lives, but patients died before it was done due to the unconscionable delay and reliance on the profit motives of private hospital chains.

How the virus can be defeated

This overview of how the pandemic proceeded in New York City makes clear that combating and defeating the pandemic is not primarily, let alone only, a medical question, but instead a political question. Nor can it be approached on a local or even national level—the same basic processes are playing out everywhere, and the spread of the virus anywhere is a threat to public health everywhere.

While the pandemic has subsided substantially from the mid-April peak of the first wave in New York City, the resumption of both public schools and indoor dining later this month, combined with the broader back-to-work and back-to-school drives, make a serious second wave coinciding with the fall and flu season inevitable—unless measures are taken to finally mount a serious response.

Workers already know what is needed and, indeed, have been demanding a serious response to the pandemic for months. The fundamentals of an effective public health approach to the pandemic must include the shutdown of nonessential businesses and schools; full compensation to workers and small business owners during the pandemic; a massive investment in the health care system, creating equality of care; and a program of mass testing, effective contact tracing and quarantining of infected and exposed individuals.

The resources to implement these measures will not be handed over by the super-rich, who monopolize them, merely through moral appeals. Indeed, even as the pandemic was raging, Cuomo pushed for a budget that will cut $2.5 billion from Medicaid in the state once the pandemic ends—with this delay only a ploy to ensure that the state gets a one-time infusion from the federal CARES Act.

The ruling-class austerity drive is not confined to Medicaid. Psychiatric wards are on the chopping block in multiple hospitals, including NewYork-Presbyterian’s Allen Hospital and Brooklyn Methodist Hospital and Northwell Health’s Syosset Hospital, which is on Long Island. The wards, which had been closed to convert into COVID-19 units and have been targeted for closure due to unprofitability, have not been reopened, whereas other parts of the hospitals have been.

At the federal level, the Democrats and Republicans allowed the $600 per week unemployment supplement to expire in July and have not been in any hurry to renew it. If they eventually do, it will be halved or worse.

To implement the necessary life-and-death measures to combat the pandemic, new organizations and a socialist perspective are needed. The unions have accepted and implemented the homicidal back-to-work policy, spearheaded by Democratic and Republican politicians alike.

Educators in New York City have already taken the lead by forming the New York City Educators Rank-and-File Safety Committee to oppose the reckless reopening of schools, and educators, students and auto workers in the US and internationally have begun forming similar organs of struggle.

Health care workers and others in New York City and elsewhere must follow this lead and build new organizations capable of opposing the pandemic and defending their lives and standards of living, both of which are under relentless attack.