Image: Emory Douglas.

“As the people of Haiti continually attest, we women in the Grandans are clear that since the coup d’etat of February 29, 2004, this has been the plan to wipe out the Haitian people and our country. We call on all women’s organizations, popular organizations, students and all to stand against this system that generates the high cost of living, misery, corruption and rape that are destroying our lives…”

– From a press release on March 17th, 2023, by Haitian women’s and popular organizations in the Grandans Department of Haiti.

As the current crisis in Haiti has metastasized into one of the worst human rights disasters in the Americas, Haitian activists in the popular movement and in diaspora are increasingly charging the US government– the key force behind the 2004 coup and subsequent occupation of Haiti– with genocide, as reflected in the above quote. They recognize that the ongoing, systematic destruction of the Haitian people as a sovereign nation is not some “random” work of “gangs’, but instead the deliberate outcome of the efforts by the US and “Core Group” powers– in collaboration with members of the Haitian oligarchy– to prevent the vast majority of Haitians from exercising genuine self-determination and popular democracy.

Ever since the Haitian people successfully overthrew slavery and colonialism in 1804, they have been subjected to interventions and policies by the French and US governments– from devastating “debt” collection to brutal military occupation, from coups to neocolonial puppet dictatorships– designed to destroy their existence as sovereign people, as an independent nation. There is extensive evidence to prove the genocidal nature of these historical interventions, including the brutality of the US invasion and occupation of Haiti between 1915-1934. The subsequent US-backed dictatorship of “Papa Doc” Duvalier who ruled Haiti from 1957–1971. Tens of thousands of Haitians were tortured, murdered, and disappeared while even more perished through the structural genocide of impoverishment, malnutrition, death by preventable disease, and extreme exploitation. As journalist Nathalie Baptiste stated:

“Papa Doc presided over the murders of an estimated 30,000 people. Thousands of others simply disappeared or were imprisoned at the notorious Fort Dimanche, a prison known for torture, mutilation and death.”

After “Papa Doc” Duvalier died in 1971, even The New York Times conceded that this US-backed dictator– who had been maintained in power and showered with millions of dollars by the US government– left this legacy in Haiti:

“The Tontons [Papa Doc’s private deathsquad system], sunglass‐wearing thugs whose fanatical loyal ty to Duvalier was rewarded with virtual licenses to torture and kill, murdered thousands of their fellow Haitians. Often they slit the throats of their victims and left them tied to chairs or hanging in market places for days as “examples” of what could happen to anti Duvalierists…By 1971, more than 13 years after he assumed power, little had changed for the great majority. Almost 90 per cent of the people were illiterate and were plagued by yaws, tuberculosis and malnutrition. Per capita income for Haiti’s 4.5‐million people was about $75 a year, compared with the Latin‐American average of about $400.” [emphasis mine]

It is documented that the notorious Tonton Macoutes received training by the US military.

Between 1971 and 1986, the US government maintained and funded the dictatorship of “Baby Doc” Duvalier, perpetuating the same system of terror and exploitation considered a “favorable investment climate” for US corporations.

Openly admitting the US domination of Haiti, Forbes magazine noted on September 22nd, 2022, that “Haiti has been a ward of the US government and international agencies for decades.” And what have been the consequences?

Compare these basic life indicators in Haiti to those in revolutionary Cuba, which broke free from US control in 1959. According to UN data compiled by the Macrotrends, Haiti’s infant mortality rate in 1959 was a staggering 192 deaths per 1000 live births. Despite advances in global health and vaccines over the past 70 years, leading to a dramatic, global reduction in infant mortality, the infant mortality rate in Haiti today remains one of the highest in the world, at 48 deaths per 1000 live births. In stark contrast, as David Blumenthal, former President of the Commonwealth Club, noted in 2016: “Since its 1959 revolution, Cuba’s infant mortality rate has fallen from 37.3 to 4.3 per 1000 live births—a rate equivalent to Australia’s and lower than the United States’ (5.8).” How is that in Haiti today, under US/ UN occupation, the infant mortality remains twelves times higher than that of revolutionary Cuba? This disparity between the countries cannot be explained by the pre-existing 1959 disparity ratio in which Haiti’s infant mortality was only approximately five times higher than that of Cuba. In other words, the disparity ratio in deaths between the two countries has more than doubled following Cuba’s revolution while Haiti has remained firmly under US domination during the ensuing decades to the present.

A similar picture of disparity emerges when it comes to indicators of acute hunger and malnutrition in Haiti and Cuba. According to data by the World Food Programme, “A total of 4.9 million Haitians – nearly half the population – do not have enough to eat, and 1.8 million are facing emergency levels of food insecurity.” [emph.mine] In contrast, regarding Cuba, the World Food Programme states: “Over the last 50 years, comprehensive social protection programmes have largely eradicated poverty and hunger.”

It is impossible to understand these disparities without taking into account and centering the significance of genocidal interventions by the US and French governments in reaction to the Haitian revolution of 1804 and the recolonization of Haiti by the US in the 20th century.

The pattern of US domination was interrupted briefly when the grassroots, non-violent mass movement of the Haitian people later called Lavalas (meaning flood in Kreyol) successfully dismantled the US-backed Duvalier dictatorship in 1986. This created the conditions for the first truly fair and free elections in 1990, resulting in the landslide election of Jean-Bertrand Aristide. The US quickly moved to support the Haitian military and elite to violently overthrow this democracy within 8 months. During the following 3 years of military dictatorship, the US-funded Haitian military and US-funded paramilitary death squad known as FRAPH killed thousands of Haitians. FRAPH leader Emmanuel (Toto) Constant was on the CIA payroll during this reign of terror, threatening to restore the old order.

The democratic resistance by the Haitian people, joined by intensive international solidarity, pressured President Clinton to support President Aristide’s return, although Clinton tried to coerce Aristide into accepting destructive US-prescribed economic policies. Aristide and the Lavalas popular movement refused to follow Clinton’s prescription. The popular, democratic Fanmi Lavalas governments headed by President Aristide– in power at two intervals between 1994 and 2004– pursued development policies that were created and driven by the Haitian people for the benefit of the Haitian people. These policies involved refusing to privatize national resources, increasing the minimum wage, investing public funds in healthcare, education, and cooperatives, subsidizing access to vital resources, and much more. The achievements in poverty reduction and human rights during this decade of popular democracy were undeniable, explaining Aristide’s vast popularity with the Haitian people and the respect for Fanmi Lavalas by international humanitarian leaders such as the late Dr. Paul Farmer. Yet these achievements, just like the brief opening to democracy in 1990, would be destroyed in a second US-backed coup in 2004, waged against President Aristide and thousands of other democratically elected officials on all levels.

Following this coup, Haitians have once again experienced the systematic destruction of their democracy and the social-economic conditions that permit them to exist as a sovereign people, as an independent nation. Crimes against humanity have returned and are intensifying.

Today, there is not a single elected official left in the entire country since the ruling US-installed Haitian Tet Kale Party (PHTK) regime has failed to hold, nor is capable of holding, fair and free elections. On January 9th, 2023, the terms of the last ten remaining Senators in Haiti’s parliament expired, leaving Haitians with no Constitutional representation at any state level. This latest development only lays bare that Haitians have been deprived of meaningful, consistent representation since the 2004 coup, through political repression and US-sponsored fraudulent elections that brought the PHTK into power.

Immediately after the 2004 coup, there was a massive wave of violent repression, targeting officials and activists with Fanmi Lavalas, the most popular political party in the country. Thousands upon thousands of people were killed. In an investigative report published by the British medical journal The Lancet on August 31st, 2006, Athena R. Kolbe and Dr. Royce A. Hutson found that during the first 22-months of the U.S.-backed coup regime, 8,000 people were murdered in the greater Port-au Prince area alone. 35,000 women and girls were raped or sexually assaulted. The violence was politically motivated as part of the coup regime’s war on Haiti’s popular movement.

Subsequent US-sponsored “elections” cemented this political repression by excluding Fanmi Lavalas from participation, as in the 2010–2011 election— dominated by the US and personally manipulated by Secretary of State Hillary Clinton– that resulted in the “victory” of PHTK godfather Michel Martelly. The next election in 2016 that put PHTK puppet Jovenel Moise in power was likewise based on blatant fraud. The result of this political repression is to deprive the Haitian people of political sovereignty.

Under the US/UN occupation, Haitians– particularly in impoverished neighborhoods that are bases of pro-democracy, pro-Lavalas activism– have been subjected to relentless massacres: first those perpetrated directly by UN occupation forces such as the 2005 massacre in Site Soley (Cite Soleil), and in more recent years those perpetrated by the US-funded/ trained Haitian National Police (HNP) and heavily weaponized paramilitaries, most notably the G9 Family and Allies, working with the PHTK dictatorship, such as the 2018 Lasalin massacre (see this video) and the 2019 massacres in the Tokyo and Site Vensan (Cite Vincent) neighborhoods. The Harvard Law School International Human Rights Clinic documented this pattern in its 2021 report “Killing with Impunity: State-Sanctioned Massacres in Haiti”. On May 21st, 2023, the National Human Rights Defense Network in Haiti released a detailed report on recent massacres in Bel Air and Cite Soleil, noting that from “2018 to the present, at least twelve (12) massacres and armed attacks have been carried out in the disadvantaged neighborhoods of Port-au-Prince. In the first 10 cases, the survivors lodged a complaint with the judicial authorities against their aggressors, most of whom were notorious armed bandits and well-known state authorities” [emphasis mine].

The paramilitaries, an outgrowth of the PHTK regime, have also utilized other forms of terror to expand their power. Rape and kidnappings have proliferated along with the massacres under the US/UN occupation and the PHTK regime. The paramilitaries have taken over neighborhoods, burning down houses, and creating a massive internal refugee crisis. In October, 2022, the International Organization for Migration (IOM) released a report showing that the number of people displaced by “gang violence” in Port-au-Prince over the past five months had tripled. Between June and August of 2022 alone, the IOM documented that 96,000 people in Port-au-Prince had been forced into internal exile. Within my own relatively small number of close friends in Haiti, there have already been several deaths and widespread displacement.

Of course, the paramilitary violence has the political function of terrorizing impoverished communities like Bel Air, Cite Soleil, and Lasalin as well as rural areas that are bases of Lavalas resistance, making it all the more difficult for people to assemble and protest for fear of their lives and the lives of their loved ones. But the violence also has the economic function of depopulating these communities, thereby facilitating land grabs. Such brutal dispossession was evident in the early years of the PHTK dictatorship under President Martelly.

Moreover, the paramilitary violence is designed to force people to accept the structural genocide being imposed onto them by the PHTK regime, implementing the austerity dictates of the IMF and the US model of neoliberal “development”, something the Haitians have called the “death plan”. Like IMF-imposed “structural adjustment programs” throughout the Global South, the “death plan” involves these measures by the ruling regime backed by the US and the IMF:

+ Engaging in pervasive corruption and the massive looting of public funds.

+ Perpetuating land grabs and the dispossession of Haitian farmers, including by former PHTK President Jovenel Moise himself to enlarge his personal banana republic, as well as the plunder of Haiti’s vast natural resources (gold, petroleum, bauxite and more) by domestic oligarchs and foreign corporations. The “open” investment climate supported by the PHTK regime is noted in this 2018 US State Department Report on “doing business in Haiti”.

+ Underwriting the super-exploitation of Haitian workers like the Caracol Industrial Park initiative with the Clintons.

+ Eliminating government subsidies on staples such as fuel, consequently plunging even more people into misery.

Predictably, in the aftermath of an agreement with the IMF made in June, 2022, the PHTK regime proceeded to eliminate fuel subsidies in September, 2022, resulting in cost-push inflation ruthlessly punishing the poor majority. By March 2023, a record 4.9 million people were experiencing acute hunger, nearly half the population. Haiti’s food inflation is among the highest in the world, increasing by 48% between February 2022 and February 2023.

The Haitian people have consistently shown steadfast resistance to the US-backed coup and to the neo-colonial policies of the “death plan”. Witness the huge mobilizations right after the coup calling for the return of President Aristide, as captured by the documentary “We Must Kill the Bandits”. Witness the immense protests against Jovenel Moise despite lethal police repression. Witness the courage of activist students like Gregory Saint-Hilaire who organized on his campus and was assassinated by police on October 2nd, 2020. Witness the courage of journalists like Romelson Vilsaint who was shot in the head and killed by police on October 30th, 2022, for his activism. Witness the courage of so many survivors who are still willing to speak out in the face of ongoing terror. Witness the singular act of resistance by Karl Udson Azor on May 21st, 2023, a medical student who publicly took off his shirt and shoes and laid them alongside a Haitian flag on the steps of the Monument of the Heroes of Vèrtières in Cap-Haitien, erected to the last battle of Haitian independence. Azor handed out his money to passing strangers, then sat down, doused himself with gasoline, and burned himself to death in protest over the ongoing destruction of Haiti, as reported in the Haitian media.

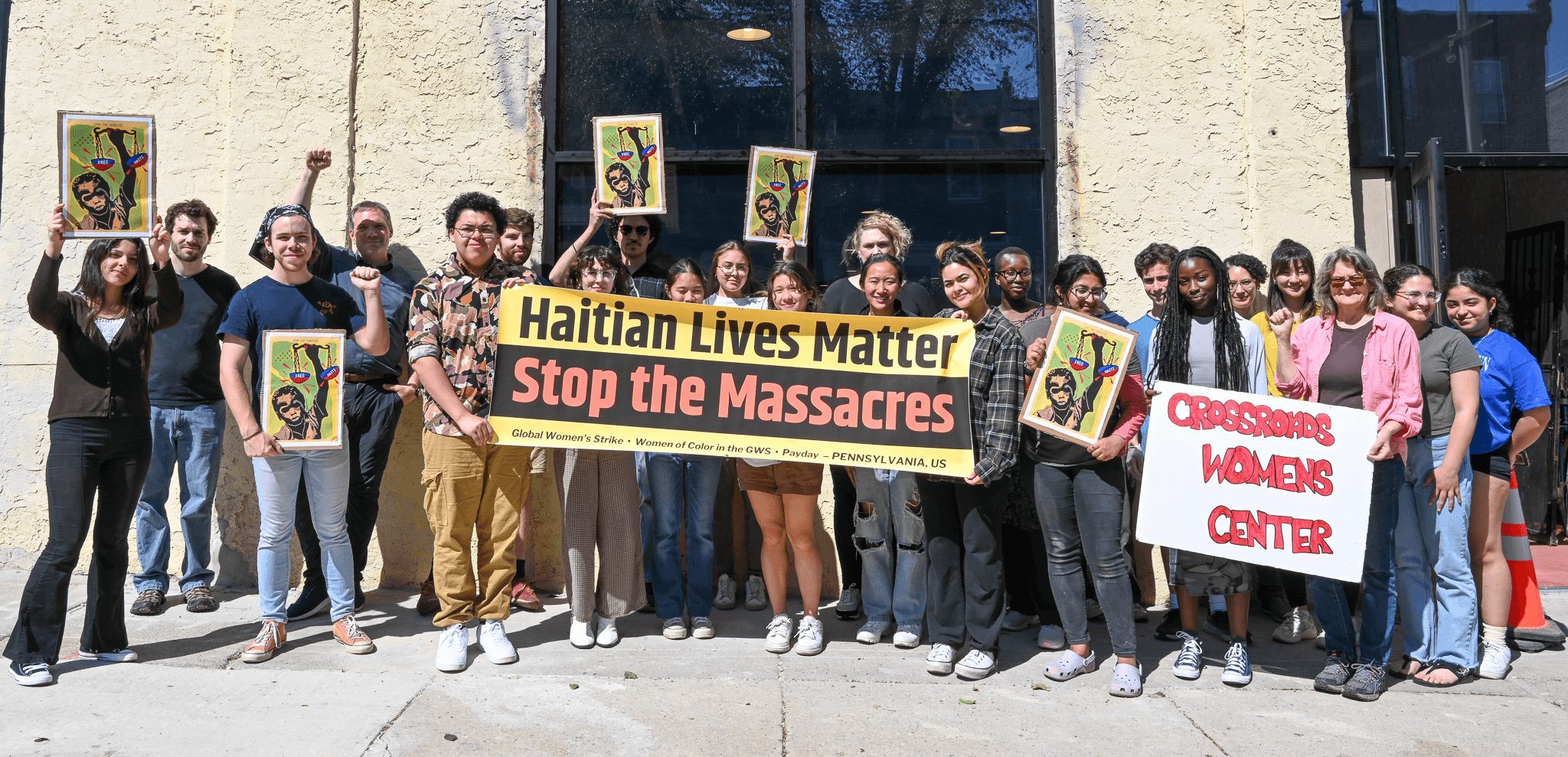

In the face of this resistance to mounting genocide, the Haiti Action Committee put out a call for protests throughout the US and the world on May 18th, 2023, Haitian Flag Day. The actions were coordinated to raise international solidarity with the Haitian people and their struggle for national liberation against the US-installed PHTK dictatorship and ongoing US/ UN occupation.

Art by Emory Douglas

Emory Douglas, revolutionary artist and former Minister of Culture of the Black Panther Party, recently created this art in solidarity with the people of Haiti. His art was widely taken up by solidarity activists around the US and the world for May 18th Day of Action. At the top of his art, he chose the words: “Stop the Genocide”, based upon internationally recognized criteria. Similarly, the ongoing, systematic destruction of Haiti as a nation conforms to the criteria established in The Convention on the Prevention and Punishment of the Crime of Genocide (1948) by the United Nations.

Dozens of organizations within and beyond the US endorsed and participated in these actions. Protests inside of the US were held in San Francisco, Washington, D.C., Los Angeles, San Pedro, Atlanta, and Philadelphia. Beyond the US, there were protests in London, Belize, and Guyana. All protests were unified in demanding that the US government and the Core Group:

+ Stop using US tax dollars to fund the brutal Haitian police and affiliated death squads such as the G-9 responsible for gross human rights violations.

+ Stop supporting the Ariel Henry dictatorship.

+ Stop attacking and deporting Haitian refugees. Within one year, the Biden Administration has violently deported more Haitians than the previous three US presidents combined.

+ No more foreign intervention in Haiti. Support the right of the Haitian people to establish their own transition government free from US and Core Group interference. Oppose the fiction– being perpetuated by the Biden Administration– that the Ariel Henry dictatorship is capable of organizing fair and free elections.

May 18th Protesters in Philadelphia holding up Emory Douglas’ art.

It is past time for the world to act in solidarity with the Haitian people. Haiti, historically and currently, continues to live up to the true meanings of revolution, liberation, and solidarity. The mobilizations on May 18th were another step towards this goal of intensifying international solidarity. As called for in the press release of the women’s and popular organizations of the Grandans, international solidarity is needed now to stop the genocide that is unfolding in Haiti, a genocide made in the USA, subsidized by US tax dollars, and aided and abetted by the “Core Group” and the UN. The array of attacks against Haiti’s grassroots movement for national liberation includes military interventions, fraudulent elections, phony economic assistance, media disinformation to maintain the status quo that benefits foreign multinationals and the Haitian oligarchy. Mobilizations are needed globally to condemn US and UN support for the Ariel Henry dictatorship and to end their policies that are destroying lives in Haiti. Solidarity actions including disruptive non-violent forms of resistance will need to be employed on greater and greater scales–in coordination with the decisive resistance on the ground in Haiti– until the Haitian people can complete their heroic revolution of 1804 and claim true victory once and for all.

Selma James at a May 18th Protest in London organized by Global Women’s Strike.