Genevieve Leigh

The epidemic of opioid addiction in the US, which has reached never before seen heights in the past two years, has put an immense strain on the already resource-starved US health care system. Among the most devastating consequences of this crisis has been the thousands of children who lose their parents to addiction every day. These children have flooded the foster care system, and their cases have exhausted social services.

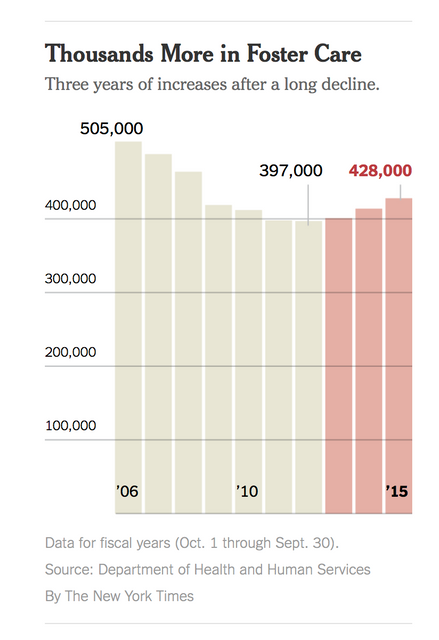

According to data from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services, in 2012, 397,000 U.S. children were in foster care. By 2015, that number had risen 8 percent, to 428,000. There is no concrete data yet for 2016; however, experts predict that the past two years—the height of the opioid epidemic so far—has increased that number dramatically.

A recent study published by the Annie E. Casey Foundation found that in 14 states the number of foster kids rose by more than a quarter between 2011 and 2015.

States that are experiencing a massive influx of children into protective custody all face similar problems, with varying degrees of severity. None are equipped with the resources to adequately deal with the crisis. Three of the hardest hit states have been Maine, Florida, and Ohio.

Thousands more children are now in foster care

Thousands more children are now in foster care

Maine

More than 1,800 children were reported to be in foster care across the state of Maine in 2016—a nearly 45 percent increase in foster children since 2011.

Last year, 376 people died from drug overdoses in Maine. This is the highest number ever recorded for the state and marks a 114 percent increase over a period of just four years, coinciding with the rise of the opioid crisis. Moreover, more than 1,000 children were born addicted to drugs in Maine last year, with the majority of the cases involving some form of opioid.

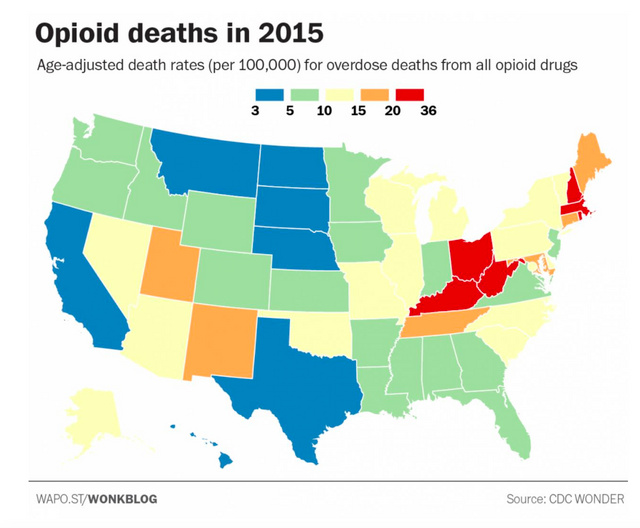

Opioid deaths in 2015

Opioid deaths in 2015

Bette Hoxie, executive director of Adoptive and Foster Families for Maine, a non-profit organization that works to provide support services for adoptive and foster parents, as well as kinship providers, recently spoke to the WSWS about the immense scope of the opioid epidemic.

“We work with about 3,100 families. Of these, 1,600 are utilizing our resources from more intensive services than just basic services. This means that they need things like clothes, they need help working through the system, they need bedding, they need much more active involvement.”

“The homes where these children are going are just not prepared with everything they need to house a child,” Hoxie noted.

“I would say nearly every single one of those cases is due to drug addiction. Of the kinship calls [when children are placed with extended family members instead of with foster families] that we get, at least 85-90 percent have been due to drug addiction, with the majority being opioids.”

Hoxie explained the effect of the spike in opioid use on the child care services: “Up until about 8 or 10 years ago, when children were coming into protective services, they were placing kids with foster care families until they could reunite them with their families or place them in permanent homes.”

“Over the last few years—in a large way, to deal with the sudden influx of such high numbers of children—there is more and more use of family members. There is definitely a strain on the system. We have 1,900 children in care, and we have 1,200 licensed foster homes.” Hoxie expressed concerns that some of these children end up in homes where the caregivers, often grandparents, are on fixed incomes and struggle to provide for the children.

Speaking on the opioid crisis more generally Hoxie added, “The biggest thing we are struggling with here in Maine is recovery options. ... When a family with addiction problems reaches out for help and they hear ‘Well, it will be three months before we can get you into a place,’ these people lose a lot of hope.”

Ohio

The state of Ohio has one of the nation’s highest overdose rates. In 2016, 4,149 deaths from drug overdose were reported, showing a 36 percent jump from the year before. In 2015, an astounding one in nine heroin deaths nationwide occurred in Ohio, a number that has likely jumped even higher since.

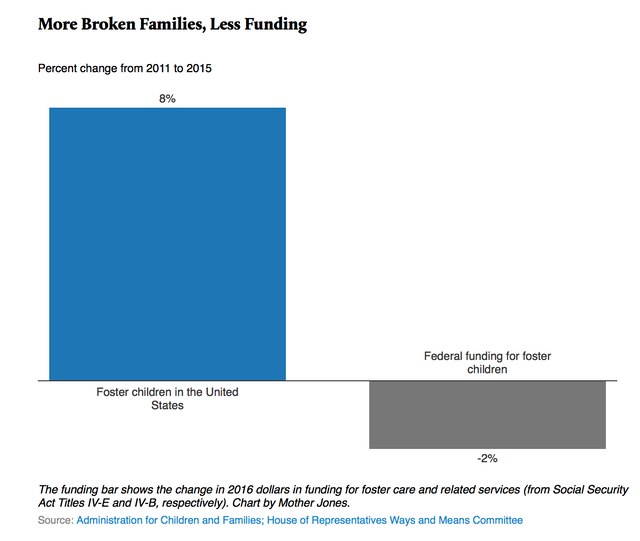

Ohio’s foster population has gone up nearly 10 percent, with more than 60 percent of children in the system because of parental drug abuse. The situation in Ohio is unique, not only because the opioid epidemic is so severe, but also because it is possibly the most resource-starved state in terms of child care services. The state ranks 50th for state share of children services total expenditures. In fact, Ohio state expenditures for child services are so low that if the number doubled, it would still remain 50th in the country.

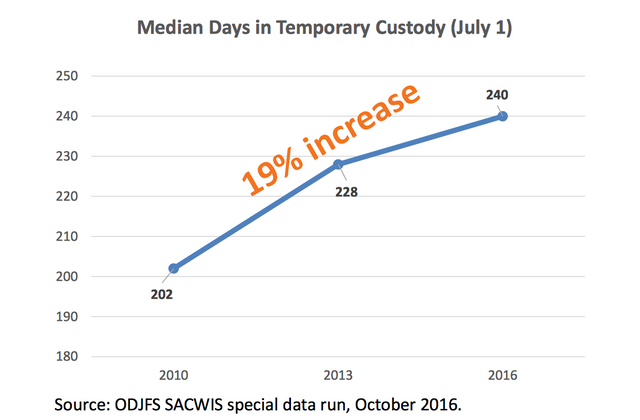

Scott Britton, who works for Public Children Services Association of Ohio, told the WSWS: “The drug epidemic really has caused a crisis across the board. We have 11 percent increase of children in custody and 19 percent increase in retention rate. We have some 2015 data that showed that 28 percent of the parents of kids who were taken from their homes were using some type of opioid. So that means more than one in four and almost one in three. This is not counting kinship care or other ways a child might come in. We suspect that number has only gone up in 2016, considering that back in 2015 we were not seeing near the same volume of opioid use as we had in 2016 and which continues today.”

Median days in custody

Median days in custody

“It is affecting just about every facet of the foster care system. Some come into our care because they were born with addiction, others because they have experienced severe neglect. They very often come in with a lot of trauma from their experiences, which complicates things. Sometimes placing them with a typical foster family is not what’s best due to the severity of their issues.”

Another major problem, mentioned by every charity group, nonprofit, and social service worker who spoke to our reporters, is the effect the pressure has had on social workers. Britton explained that Ohio is no different: “These workers are emotionally exhausted. They are often the ones who are left with tasks like telling a child that one of their parents, or sometimes both of their parents, have died from overdose, for example.

“Our caseworkers are really committed to reunifying children with their parents. That is our number-one goal. They work really hard to get parents into treatment. Unfortunately, they are seeing less and less of that, which is really tough on their morale. We did a survey in 2016 and found that one out of every four caseworkers left their positions. I suspect they just become exhausted from taking that emotional stress home.”

Florida

The worst manifestation of the opioid epidemic in Florida is in the state’s 12th Judicial Circuit Court, which includes Sarasota, Manatee and DeSoto counties. One figure that sheds light on the severity of the situation in this area is the number of doses of Narcan (Naloxone), the drug that reverses the effects of an overdose, being administered. In July 2015, emergency responders in this area administered a record 281 doses of the “miracle drug.” By July 2016, that number had more than doubled to 749. Officials in the area remain unable to stem the epidemic.

More broken families, less funding

More broken families, less funding

Kathryn Shea is the president and CEO of the Florida Center for Early Childhood, which is an early childhood mental health provider. Shea works in the heart of the Florida epidemic.

Shea told the WSWS: “The numbers we are seeing in Sarasota of kids in care we have never seen before. There is no question that the biggest cause is substance abuse, and the primary drug is opioids. Our children have been dramatically impacted, as have our babies.”

When asked about reports that Florida and other states such as Oregon and Texas have been forced to have children sleep in state buildings because there were no foster homes available, Shea responded, “Yes, that has happened here. Not as often, because they are constantly recruiting foster parents. Instead, here they often have to go over their waiver of five kids per parent.”

Shea also commented on the effect this crisis has had on those who work in the field, “Our turnover rate for social workers is just horrible. It’s very hard to keep cases managers and investigators. A lot of these workers are very young and have just gotten out of college or just have high school degrees and don’t have a lot of life experience to help buffer the intense situations that they have to deal with. Let me put it this way—I have been in this industry 37 years and it is still difficult for me. Often they are traumatized by what they go through on the job. They end up with secondary trauma from what they see and do. Honestly, from all my years in the field, I’ve never seen the situation this bad.”

When asked about what sort of impact the Trump health care plan, which would end Medicaid as an entitlement program, might have on the children affected by the opioid epidemic Shea said it would be a disaster. “Most of our families are on Medicaid. This covers over 90 percent of our kids. The services for them would be dropped. What we are talking about is the difference between life and death for children. I am not saying that lightly. I am very serious. We will be hurting the most vulnerable population. I think it’s an absolute crime.”

Asked to explain what she thought was driving the opioid epidemic Shea told the WSWS: “Well, I think the real root cause of this is poverty. Many of these people were raised in poverty and don’t see a way out of it. Many of them have experienced serious trauma and have never been treated properly because they don’t have the money and they use drugs to self-medicate, and to deal with the pain.”

deutsches-museum.de

deutsches-museum.de