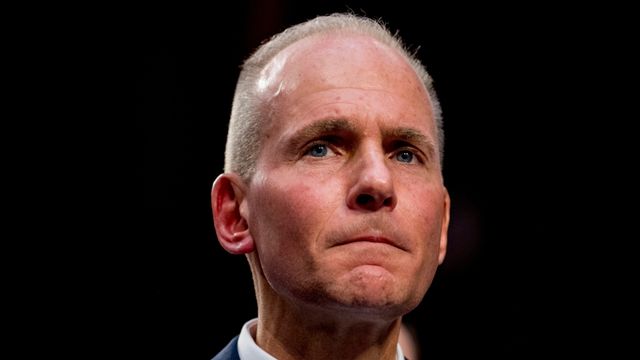

Tomas Castanheira

Relying on emergency votes and employing brutal police force, Brazilian state governments are imposing pension “reforms” against state-level public sector workers that will all but prevent workers from retiring. The legislation aims at bringing public employees in the states down to the same poverty pension schemes imposed by Bolsonaro in the private sector and on federal public sector workers earlier in the year.

Since November, unions have shut down and isolated teachers’ strikes across the country, preventing a unified working class resistance and opening the path to the action of state governments, many of them controlled by the self-described political opposition to Bolsonaro led by the Workers Party (PT), which also dominates the largest unions.

Police prepare to attack protesters at Ceará state building [Credit: Leticia Lima]

Police prepare to attack protesters at Ceará state building [Credit: Leticia Lima]

Last Wednesday, December 20, the PT governor in the northeastern state of Ceará, Camilo Santana, became the latest to impose a new pension scheme after the ruling PT caucus requested an emergency vote and the state’s Military Police were called out to confront protesting workers at the state capitol building.

Santana is following in the footsteps of other opposition-led governments in the Workers Party’s historic heartland, Brazil’s impoverished Northeast, where alliances headed by the PT and its smaller partners, the Socialist Party (PSB) and the Maoist Communist Party (PCdoB), rule eight out of nine states. A week before, police repression was employed to push through a similar proposition in Piauí. The ruling PCdoB in Maranhão rammed through its pension reform with a rushed vote, and Bahia and Rio Grande do Norte are due to hold their own votes in 2020.

The PT’s and PCdoB’s votes have also been crucial for the imposition of the reform elsewhere, such as the Amazonian state of Pará, where the PT’s state leadership issued a cynical public letter claiming its approval of the state pension reform was part of a “responsible” attitude to “reduce the damage” of Bolsonaro’s measures. In other states, wherever the PT is formally excluded from government due to particular political arrangements, it postures as opposing the reforms by concocting differences between the measures proposed in different states’ legislation.

Workers confront police in Ceará [Credit: Fuaspect]

Workers confront police in Ceará [Credit: Fuaspect]

This is above all exposed in São Paulo, where Francisca Seixas, an official with both the National Education Workers Confederation (CNTE) and the local APEOESP state teachers’ union, was forced to respond to criticism of workers for the union’s support of the Maranhão government. Seixas attempted to divert criticism by claiming that pension contributions in Maranhão were not raised uniformly for all workers. For teachers, however, pension taxes in the state will reach 14.5 percent, even higher than the 14 percent being rammed through in São Paulo. She went on to add that criticism of the PCdoB government in Maranhão was unwarranted, because “ to slander governor Flávio Dino at this point is in the sole interest of the most backward sectors of the Brazilian right wing [our emphasis].”

Even more cynical was the posturing of the PT-controlled CUT national union federation in the state of Sergipe, where it stated that the local pension reform being proposed by the government was “not in keeping with the national opposition of the [Workers] Party to Bolsonaro’s Pension Reform.”

The CUT’s claims reek of dishonesty. The PT’s “struggle” on the national level was a fraud, and workers’ demonstrations and strikes were sabotaged even as PT governors openly lobbied to have the federal reform expanded to include state workers so that they could claim clean hands, rather than having to impose the attacks themselves in their own states and call in the police to beat protesting workers.

Military Police phalanx deployed against Ceará protesters [Credit: Tarcisio Aquino Filho]

Military Police phalanx deployed against Ceará protesters [Credit: Tarcisio Aquino Filho]

Now the same theatrics are being employed in the states, with the particularly treacherous role of the emergency votes being held while teachers are on summer recess. For almost two months, public sector unions have called for token strikes to let off steam, shutting them down at the first opportunity. In the southern state of Rio Grande do Sul, where the strikes saw the most militant response across the public sector and gained wide support from private sector workers and even from small retailers, the local CPERS teachers union lured workers off the picket lines based on an injunction against the pension reform granted by the Supreme Court at the request of the pseudo-left Socialism and Liberty Party (PSOL).

After a massive demonstration at the state capital of Porto Alegre on December 17, the union and PSOL officials claimed the local pension reform was “dead in courts” because of the injunction and that workers should call off the strike and focus on camping out in front of the state parliament to guarantee that they would be paid their wages for the days on strike. Barely a day later, the injunction was struck down, and the reform was swiftly passed by the legislators. The union then dismantled the camp in front of the legislature and claimed that a meeting in the city of São Leopoldo, part of the Porto Alegre industrial belt, had authorized it to focus exclusively on guaranteeing that workers would be paid for the days on strike, despite large votes in favor of continuing the strike against the pension reform, even without strike pay, in Porto Alegre and other regional centers.

The PT’s widespread efforts in favor of the federal and local attacks on pensions in Brazil expose once more the party’s hostility to the working class. They have also given the lie to the false claims of its leaders, first and foremost former President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, that the party is “the opposite of Bolsonaro.”

But it also exposes the treacherous role of the petty-bourgeois pseudo-left groups that work with the sole goal of using the overwhelming hostility of workers to Bolsonaro to restore the PT’s authority among them.

Addressing the policies of the right-wing PT governor of Bahia, Rui Costa, on December 15, the Morenoite Resistência group, operating inside PSOL, attempted to dismiss the PT’s collaboration with Bolsonaro with a reference to the so-called “Stockholm syndrome,” a condition popularly known to affect individuals who suffer severe abuse and, in a state of deep desperation, appear to develop affection for their abusers—most frequently in kidnappings. The article claims that despite suffering a “coup” in the 2016 impeachment of PT President Dilma Rousseff, which the PT accepted without any attempt to mobilize workers in its defense, the party “believes it can reestablish a social pact with the bourgeois sectors and return to power.”

Beyond the pseudo-Marxist rhetoric about “bourgeois sectors,” implying that the PT is not one of them, the aim of the article is to relieve the PT—as a supposed victim of extreme abuse—of any responsibility for its own policies. It also blames the working class for breaking with the party, and demands instead that workers work to rescue the PT from its captives and push it left.

This is even more bluntly stated by another of the myriad Morenoite tendencies embedded in PSOL, the Left Socialist Movement (MES), whose leader Luciane Genro was responsible for the Supreme Court injunction used to lure Rio Grande do Sul teachers off the picket lines. The MES openly promoted the Greek Syriza and the Spanish Podemos as providing some new road to socialism. After feigning surprise over their betrayals, it now attempts to carry out the same services for the pro-imperialist Democratic Socialists of America in the US and Democratic Party House Representative Alexandria Ocasio-Cortez.

After joining the Brazilian right wing in the campaign for Rousseff’s impeachment in 2016, the current has done a complete about-face, defending unity with the PT and extolling Lula as “a mass leader of the opposition against authoritarianism and the far right’s project,” despite “their strategy of cooperating with banks, construction companies and big capitalists.”

The MES’s position exposes the class character of the pseudo-left’s support for the PT. Their posturing as loyal “left critics” of the PT serves as a means of channeling mounting social opposition behind this bourgeois party in order to head off and suppress the kind of explosive working class revolts that have swept much of South America.

The politics of these layers can only help prepare a repeat of the great betrayals suffered by the working class in Brazil and throughout the continent in the 1960s and 1970s. Breaking the grip of the PT and its pseudo-left satellites on the workers movement requires an intractable struggle for the political independence and international unity of the working class through the building of a Brazilian section of the International Committee of the Fourth International.