Tom Peters

Legislation introduced to New Zealand’s parliament late last month would vastly expand the power of state agencies to censor and remove online content deemed “objectionable.”

The Films, Videos, and Publications Classification (Urgent Interim Classification of Publications and Prevention of Online Harm) Amendment Bill is presented as a response to the Christchurch massacre on March 15, 2019, in which fascist Brenton Tarrant killed 51 and injured another 49 at two mosques. The gunman live-streamed a video of his terrorist attack and shared it on social media.

In a May 26 statement, Internal Affairs Minister Tracey Martin said the Bill would help to fulfill the government’s commitments under the so-called Christchurch Call to Action. Launched last year by the New Zealand and French governments, this initiative urged governments and corporations “to eliminate terrorist and violent extremist content online.”

Ardern with Deputy Prime Minister Winston Peters and Governor-General Dame Patsy Reddy at the swearing-in of the Cabinet on 26 October 2017 (Image Credit: Governor-General of New Zealand /Wikipedia)

Ardern with Deputy Prime Minister Winston Peters and Governor-General Dame Patsy Reddy at the swearing-in of the Cabinet on 26 October 2017 (Image Credit: Governor-General of New Zealand /Wikipedia)

Prime Minister Jacinda Ardern has campaigned internationally for the Christchurch Call. Speaking at the United Nations last year she said it would combat the online promotion of terrorist violence and “language intended to incite fear” against ethnic and religious groups.

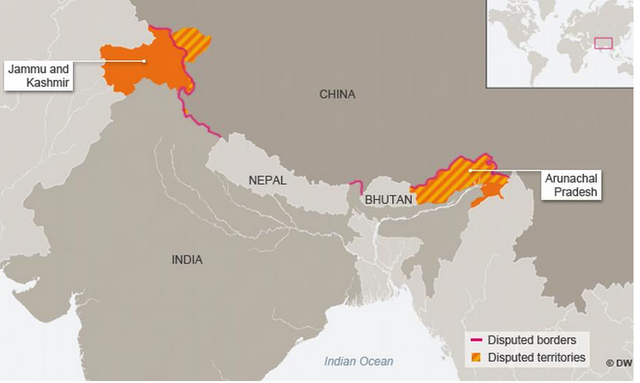

What constitutes “extremist” or “terrorist” content, however, is determined by the state. The Call has been signed by more than 50 countries including India, Japan, Britain, Australia, Canada, Germany and Indonesia. India has blocked internet access in Jammu and Kashmir, while Indonesia last year blocked access in Papua province—in both cases to assist in the repression of separatist movements labelled “extremist” or “terrorist.”

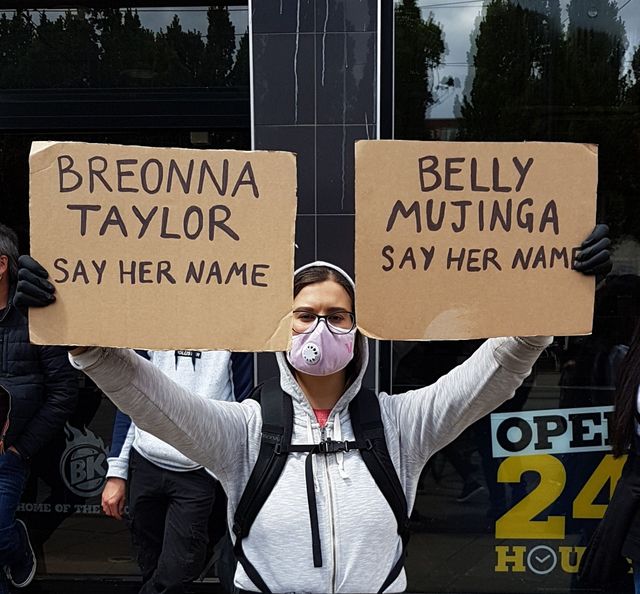

US President Donald Trump has labelled protests against killings by police as the work of “terrorists,” in order to justify violent repression.

While the Christchurch Call is not officially backed by the US government, it was signed by Google, Amazon, Facebook, Twitter, YouTube and Microsoft—giant corporations that work closely with governments on surveillance and censorship, in particular of socialist, progressive and anti-war content.

The New Zealand legislation would empower the country’s Chief Censor “to make swift time-limited interim classification assessments of any publication,” including anything posted on social media sites. Content classified as “objectionable” can then be immediately blocked or censored.

An “Inspector of Publications” will be able to issue “take-down notices,” requiring online platforms such as Facebook or Google to remove “objectionable” links or be fined up to $200,000. This mirrors similar measures enacted in Australia immediately after the Christchurch shooting.

To enforce the new law, the Ardern government last year gave an extra $17 million to the Chief Censor and the Censorship Compliance Unit, essentially doubling their funding and allowing the unit to expand its staff from 13 to approximately 30 people.

The Bill would also enable the government to proceed with “the establishment of a government-backed... web filter if one is desired in the future.” The draft legislation acknowledges that such filters, which would prevent access to blacklisted websites, could “impact on freedom of expression.”

In the UK, a web filter introduced in 2013 on the pretext of combating child pornography has blocked numerous websites which had nothing to do with illegal activity.

New Zealand’s two biggest internet service providers, Spark and Vodafone, told Newsroom they support such a filter, along with the other measures in the legislation.

The lobby group InternetNZ criticised the proposal. Its chief executive Jordan Carter told Stuff on May 28 that the Bill “leaves a whole heap of discretion for the secretary of internal affairs about how [the filter] would work, who it would apply to, and whether it would be compulsory or not, and we don’t think that putting a really broad power like that in this legislation is a good idea.”

A press release by Internal Affairs Minister Martin vaguely stated that “content is deemed to be objectionable if… [it] is likely to be injurious to the public good.” Examples “include depictions of torture, sexual violence, child sexual abuse, or terrorism.”

The definition can easily be interpreted to include media coverage and exposures by members of the public of police brutality, fascist violence and war crimes.

Indeed, Chief Censor David Shanks has already suppressed the video of the Christchurch massacre—which appeared in news reports throughout the world—and outlawed possession of Tarrant’s fascist manifesto. Shanks also warned that reporters who quoted from the document “may” be breaking the law.

The corporate media has complied with a request from Ardern to self-censor reporting about Tarrant’s fascist views. The aim is to cover up the manifesto’s striking similarity to the xenophobia, racism and anti-socialism promoted by the political establishment.

Significantly, Internal Affairs Minister Martin, who is overseeing the internet censorship law, is a member of the right-wing nationalist NZ First Party, which has stoked anti-Chinese and anti-Muslim sentiment. Ardern gave NZ First a major role in her government, with several ministerial positions (Deputy Prime Minister, Defence, Foreign Affairs, Internal Affairs and Regional Development), because Labour essentially agrees with the right-wing party’s anti-immigrant politics.

The Greens, which are also part of the government, have made no statement about the internet censorship bill, but the party has previously made clear it supports censorship in the name of stopping “hate speech.”

All historical experience demonstrates that the danger of fascism cannot be addressed by giving more powers to the state. In the US, Europe and internationally, fascist forces are being actively promoted by governments and military-police agencies to divide the working class and defend the discredited capitalist system.

In New Zealand, successive Labour and National Party governments are responsible for encouraging the anti-Muslim bigotry that fueled the Christchurch massacre, including through their support for the criminal US-led wars against Iraq and Afghanistan.

Both major parties also utilised the so-called “war on terror” to expand the powers of the intelligence agencies to spy in on New Zealanders and internationally.

As well as pushing online censorship, the Ardern government exploited the Christchurch massacre as a pretext to further militarise the police and give more money to the spy agencies, which for years turned a blind eye to threats of white supremacist violence.

The real reason the state apparatus is being strengthened is to prepare for an explosion of mass struggles, including protests against fascist and police violence, such as those unfolding in the United States. Above all, the political establishment is seeking to suppress working-class opposition to social inequality, unemployment and poverty in New Zealand, which is expected to reach levels not seen since the Great Depression.