IDPI

IDPI

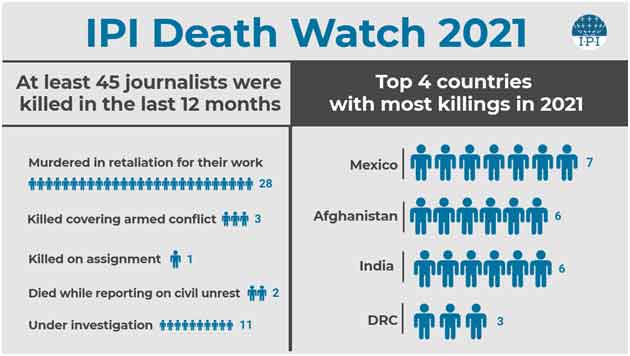

In 2021, a total of 45 journalists were killed in connection with their work, IPI research revealed on December 29, 2021. The sombre tally reflects the continued risks of doing journalism and reaffirms journalist safety as a global challenge. International Press Institute (IPI) calls on authorities to end impunity for these crimes and to ensure the protection of journalists, who must be able to do their work freely and safely.

The IPI global network published its yearly Death Watch on December 29, 2021. IPI’s research shows that since the beginning of 2021, a total of 45 journalists were killed in connection with their work, or lost their lives on assignment. Of these 45 journalists, 40 were male and five were female. A total of 28 were targeted due to their work, while three were killed while covering conflict, two lost their lives covering civil unrest, and one journalist was killed while on assignment. Eleven cases are still under investigation.

The Death Watch includes names of journalists who were deliberately targeted because of their profession – either because of their reporting or simply because they were journalists – as well as those who lost their lives while covering conflict or while on assignment. IPI’s list includes journalists, editors, and reporters, as well as media workers who directly contribute to news content, such as camerapersons.

IPI’s statistics are based on the organization’s regular monitoring of attacks on journalists. In addition, IPI works closely together with its network of members and with local journalism organizations to assess whether the killing of a journalist was likely to be work-related or not.

Deliberately killed

Of the journalists included in the Death Watch, IPI classifies 28 as targeted due to work, meaning that there are clear indications that the victims were deliberately killed due to their profession – either in retaliation for specific reporting or simply for being a journalist. The list includes independent Somali journalist Jamal Farah Adan, who was shot by gunmen on March 1. The extremist group Al-Shabaab later claimed responsibility. In July, Mexican journalist Ricardo Dominguez López, owner of news website InfoGuaymas, was shot to death in the parking lot of a supermarket on his 47th birthday. These are just some of the more than two dozen abhorrent killings around the world.

Some – but not all – journalists had received death threats before they were murdered. For instance, Shannaz Roafi, Sadia Sadat, and Mursal Wahidi worked for the independent radio and TV station Enikass in Afghanistan, which had received threats from extremist groups for broadcasting television shows. Rasha Abdullah Al-Harazi, a journalist from Yemen who died in a targeted car bomb attack while she was nine months pregnant, had received many threats in the months before her death, Khalid Ibrahim of the Gulf Centre for Human Rights told IPI. “By phone she was told to stop doing journalism”, he said. “But we didn’t know it would be this serious.”

In addition to the 28 targeted killings, IPI classifies 11 killings as “under investigation”. This designation means that there are grounds to suspect that the journalist’s death may have been a targeted killing, but that more information is needed to be able to confirm this. One example is the murder of former Reuters journalist Jess Malabanan in the Philippines, who was killed on December 8 by assailants on a motorcycle while he was watching TV. As Malabanan had worked on a prize-winning Reuters production on President Duterte’s drug war in 2018, there is suspicion that the killing may have been journalism-related. IPI is working closely with local journalism organizations to follow this and other cases for potential updates.

In many cases, the failures of states to investigate the murders of journalists makes it difficult to assess whether a killing is work-related, requiring researchers to rely on circumstantial evidence. Determinations may be updated to reflect new information. In addition, IPI is also looking into several other cases of journalists who were killed in 2021, for which there is currently no indication of a connection to their work. Although these cases are not listed on IPI’s Death Watch, IPI continues to follow them in collaboration with local media organizations.

Three journalists were killed covering armed conflict, including Maharram Ibrahimov, a reporter for the Azerbaijani state news agency AzerTag, who was killed in a landmine explosion on June 4 in Azerbaijan’s Kalbajar region. Two journalists were killed covering civil unrest, including Burhan Uddin Mujakker, who was shot in the neck while covering a political clash in Bangladesh in which eight other people suffered bullet injuries. One Indian journalist, Arindam Das, died on assignment. Das drowned while covering the rescue mission of an elephant from a river. These deaths reflect the continued hazards of the journalistic profession.

A global problem

The Death Watch reveals that killings of journalists have occurred in almost every part of the world, confirming that journalist safety is a global problem that is not confined to particular regions. Asia and the Pacific was the deadliest region for journalists in 2021, with 18 killings, most of which occurred in India (6) and Afghanistan (6). Ten killings occurred in the Americas, which led the list in 2020. Seven journalists were killed in Mexico, one in Colombia, one in Guatemala, and one in Haiti. Six journalists were killed in Europe: two in Azerbaijan, one in Georgia, one in Turkey, one in the Netherlands (listed as Under Investigation), and one in Greece. Two journalists were killed in the MENA region, both in Yemen, while nine journalists were killed in Sub-Saharan Africa, most of whom in the Democratic Republic of Congo (3), followed by Burkina Faso and Somalia (both 2).

Like last year, more journalists were killed in Mexico (7) in 2021 than any other country in the world. All seven cases were targeted killings. According to IPI’s analysis, journalists researching local politics and organized crime, including drug trafficking, are especially at risk. Most of the targeted journalists were examining these or related topics. Another explanation for the high number of killed journalists is the level of impunity. According to ARTICLE 19 Mexico, in only one of these seven cases have suspects have been arrested. The continued high number of killings confirms Mexico’s status as one of the deadliest countries for journalists to work. Despite this tragic status quo, the government there has decided to stop funds allocated for upholding the Law for the Protection of Human Rights Defenders and Journalists (LPPDHP).

After Mexico, Afghanistan and India are the two next-deadliest countries, with six killings each. In Afghanistan, most killings occurred in relation to the violent conflict as a result of the Taliban’s takeover of the country this summer. Not included in the list are two journalists who died at the airport from a bomb explosion while trying to escape the country.

Of the six journalists who lost their lives in India, two were targeted due to work, like Chennakesavulu, who was stabbed to death by a suspended police officer after he discovered the officer’s involvement in a gambling and tobacco smuggling ring. Another two cases are classified as under investigation (potential targeted killings). One journalist was killed while on assignment, while another was killed while covering civil unrest.

In the Democratic Republic of Congo, three journalists were killed because of their work, like Joel Mumbere Musavuli, director of the privately owned broadcaster Radio Télé Communautaire Babombi (RTCB), who was stabbed to death alongside his wife by militiamen who had threatened him after Musavuli had covered armed groups in one of his shows. In Burkina Faso, 43-year-old David Beriáin, an experienced war reporter, and 47-year-old cameraman Roberto Fraile, were killed in an attack on a ranger patrol. The two journalists from Spain had been working on a documentary about combating poaching in the region, which is known for violent activity.

Importantly, journalists were also murdered in countries with relatively high levels of press freedom, which arguably shows the global nature of the risks of doing journalism. For example, high-risk crime journalist Peter R. De Vries was shot on an Amsterdam city street in broad daylight on July 6, 2021, despite the fact that the Netherlands is considered one of the countries with the highest degree of press freedom in the world. The De Vries case is currently classified as Under Investigation on IPI’s Death Watch. In Greece, crime reporter Giorgos Karaivaz was shot outside his home in Athens. As of December 2021, no suspects have been publicly identified and no arrests have been made, while public information about the status of the investigation remains scarce.

Impunity

IPI’s analysis shows an alarmingly insufficient response from authorities to the killings, leading to high levels of impunity for crimes against journalists. In only six of the 28 cases have local police reportedly arrested suspects. However, even this figure must be interpreted with caution, given that state investigations into journalist killings – insofar as they occur at all – are often deeply flawed and in some cases result in further miscarriages of justice, including arrests of innocent suspects.

Indeed, in several cases where arrests have been made, families of victims have indicated their belief that the police have arrested the wrong suspect or have arrested suspects to cover up the case, avoiding a real and thorough investigation. For example, in the case of Manish Kumar Singh, an Indian reporter working for Sudarshan TV who was killed on August 10 this year, his editor, Suresh Chavhanke, said on Twitter that the family believed the detained suspects were being used to whitewash the murder.

The failure of states to investigate many of the killings on IPI’s Death Watch occurs against a background of wider impunity for attacks on journalists. The vast majority of journalist killings around the world go unpunished, emboldening further violence and casting a chilling effect over the press everywhere. These include some of the most openly egregious murders of journalists. For example, Jamal Khashoggi, a Washington Post columnist and well-known critic of Saudi Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman, disappeared after entering the Saudi consulate in Istanbul on October 2, 2018. His body was apparently dismembered by a team of assassins sent from Riyadh and his remains have never been found. Or Ahmed Hussein-Suale, who was shot dead on January 16, 2019, in Accra, Ghana, while returning home from work. In 2018 Hussein-Suale was part of an investigation that revealed corruption in African football right before the World Cup. Police arrested six people on suspicion of being involved in the murder, but later released them all due to lack of evidence. To this day, the assailants and the masterminds who ordered the killing remain unidentified.

IPI has repeatedly called on local authorities to end impunity for crimes against journalists and will continue to do so. “Impunity for such killings fuels violence against the media at a time when the free flow of news is more important than ever”, IPI Deputy Director Scott Griffen said. “States must do more to solve attacks on journalists. And the international community must sanction regimes – such as Saudi Arabia – complicit in such killings.”

Small decrease, but no celebration

The last few years have seen an overall decrease in the number of killings of journalists. For reference, 102 killings were registered in 2011, while 2016 saw 120. As IPI’s statistics include journalists who are killed while covering conflict or on assignment, this decrease can partly be explained by the waning of several violent conflicts around the world. For example, the conflict in Syria led to 12 killed journalists in 2016; this year IPI did not register any case in the country. In 2017, 11 killings of journalists were registered in Iraq; this year the number was zero. While the decreased number of journalist killings is clearly a positive development, even one case is one too many. All 45 killings this year are a tragedy. All journalists must be able to do their work safely.

Moreover, the number of journalist killings is not in itself a reliable indicator for the state of press freedom. “Waves of violence against the press may lead to pervasive self-censorship whereby journalists avoid topics or beats that put their lives at risk”, Griffen said. “This is worsened by a climate of impunity in which killers are not held to account. IPI stands with the families and colleagues of all journalists killed for their work in 2021, and we demand that those responsible be held to account.”