Kevin Reed

On April 10, the tech corporations Apple and Google announced a collaborative effort to introduce COVID-19 contact tracing capabilities into their mobile technologies. In a joint statement, the Silicon Valley tech giants wrote that they intended to “enable the use of Bluetooth technology to help governments and health agencies reduce the spread of the virus, with user privacy and security central to the design.”

The statement elaborated further, “Apple and Google will be launching a comprehensive solution that includes application programming interfaces (APIs) and operating system-level technology to assist in enabling contact tracing. Given the urgent need, the plan is to implement this solution in two steps while maintaining strong protections around user privacy.”

Step one of the accelerated development plan will allow official apps from public health authorities to interoperate between the Android and iOS mobile operating systems. In step two, the companies will enable Bluetooth-based contact tracing in their underlying platform as part of the core capability of smartphones.

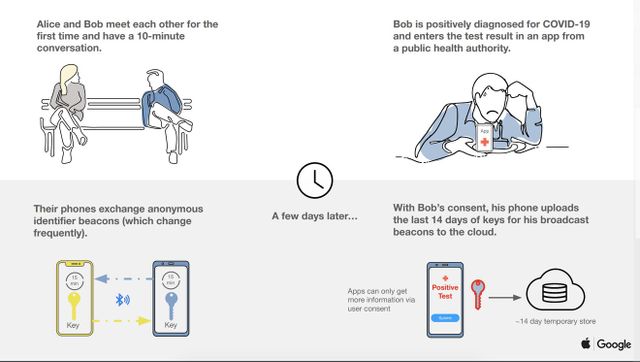

Apple and Google announced on April 10 the joint implementation of contact tracing technology into the Adroid and iOS operating system [Photo credit: Apple/Google Infographic]

Apple and Google announced on April 10 the joint implementation of contact tracing technology into the Adroid and iOS operating system [Photo credit: Apple/Google Infographic]

The second phase of the project, according to the joint statement, “is a more robust solution than an API and would allow more individuals to participate, if they choose to opt in, as well as enable interaction with a broader ecosystem of apps and government health authorities.” The short press statement then repeats again for a third time, “Privacy, transparency, and consent are of utmost importance in this effort, and we look forward to building this functionality in consultation with interested stakeholders.”

Contact tracing is a primary scientific method for responding to and combatting a pandemic. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), contact tracing is the process of locating everyone who comes into direct contact with someone who has been infected and then taking certain specified actions to contain the virus from spreading further. The CDC calls for monitoring contacts of infected people after notifying them of their exposure and then “ensure the safe, sustainable and effective quarantine of contacts to prevent additional transmission.”

Most people who get COVID-19 are infected by their friends, neighbors, family or work colleagues, so these relationships are the ones that contact tracing is concentrated on. In countries and regions that have combined contact tracing with widespread testing—such as South Korea, Singapore and Hong Kong—death rates have been relatively low compared to countries, like the US, that are testing only those who show symptoms of COVID-19.

Traditionally, contact tracing requires the creation of large teams of trained professionals who trace relatives, neighbors and friends to find anyone who has come into contact with a sick person or someone who has died. The contact tracers stay in touch with those testing negative and ask questions, look for symptoms and recommend courses of action.

With the development of mobile and cloud-based computer technologies, advanced contact tracing systems have already been developed and used internationally. According to a report in the Atlantic, the governments of South Korea and Singapore used a combination of smartphone location data, video surveillance and credit card records to monitor citizen activity during the pandemic.

The Atlantic report went on, “When somebody tests positive, local governments can send out an alert, a bit like a flood warning, that reportedly includes the individual’s last name, sex, age, district of residence, and credit-card history, with a minute-to-minute record of their comings and goings from various local businesses.”

According to a report in Nature, in some districts of South Korea, the contact tracing information shared with the public “includes which rooms of a building the person was in, when they visited a toilet and whether or not they wore a mask.” The South Korean government argues that the public is more likely to trust it if it releases transparent and accurate information about the virus. Many of the laws allowing the information to be made public were passed since the country’s outbreak of the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS) in 2015.

In Singapore, residents downloaded an app called TraceTogether, which uses Bluetooth technology to keep a log of those with mobile devices who are nearby. When someone gets sick, they upload the relevant data to the Ministry of Health, which then contacts the owners of all the devices logged by the infected person’s phone.

A fast-track discussion has been underway since the middle of March about the development of mobile technology-based contact tracing in the US led by the Silicon Valley tech giants. Papers have been published by leading academic and health policy research institutions and proposals have been advanced regarding guidelines for the use of location data and the collection of other information related to the pandemic.

On April 8, the American Civil Liberties Union published a document, “The Limits of Location Tracking in an Epidemic,” which is directed at US lawmakers and raises questions about the effectiveness of cell phone contact tracing capabilities. The ACLU statement says, “location data contains an enormously invasive and personal set of information about each of us, with the potential to reveal such things as people’s social, sexual, religious, and political associations. The potential for invasions of privacy, abuse, and stigmatization is enormous.”

Apple and Google are both well aware that any proposal containing the phrases “to help governments” and “strong protections around user privacy” will be viewed by the public as oxymoronic. This is why they are working to convince the public that their coronavirus initiative is only for the purpose of containing the pandemic and not a government surveillance operation.

A huge amount of data will be collected by contact tracing smartphones, such as geolocation and the device details of all those who come into contact with each person. For governments to gain access to this data—especially if it is stored in a national or international database—represents a trove of information on the entire population far beyond anything currently available.

In the case of Israel, the government of Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu moved rapidly on March 17 to pass legislation that authorized contact tracing of the public by the Shin Bet security service with previously secret technology that had been used for so-called “anti-terrorism” surveillance.

Meanwhile, there is no doubt that the aggressive collaborative effort by the Apple and Google—coming one month after a special meeting between the White House and the tech companies on March 11 to discuss the pandemic—is part of an effort make sure that any global implementation of pandemic track and trace technologies are dominated by US corporations.

With the potential for every smartphone owner on the planet—approximately 3.5 billion people—to install the contact tracing software on their devices, investors on Wall Street see an opportunity for a massive business opportunity.

Smartphone technology has the enormous potential to play a critical role in isolating and halting the spread of the coronavirus. However, with the COVID-19 pandemic intensifying national conflicts and the ruling elite exploiting the crisis to both intensify state surveillance and increase their wealth, the only way that this potential can be realized in a progressive manner is under the democratic control of the working class through the struggle for socialism on a world scale.

No comments:

Post a Comment