Parvin Sultana

Elone Kastratia STARTED a unique street art protest using Sanitary napkins with messages against sexual violence in her hometown Krlsruhe, Germany which went viral in social media. With rapidly spreading across to other countries, it was picked up by students of universities like Jamia Milia Islamia, Delhi University and Jawaharlal Nehru University. They put up sanitary napkins in various spots in the universities. The idea behind using sanitary napkins to start such awareness campaign was to use blunt hard hitting methods in starting a dialogue around sexual harassment of women. The means used raised many eyebrows in a society where sexism continues to be rampant.

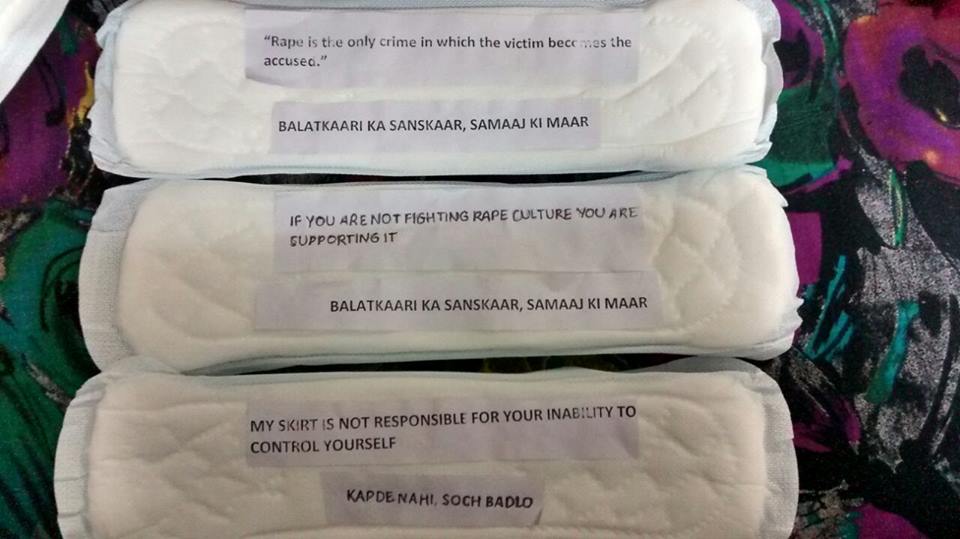

Menstruation continues to be a hushed up women’s issue. Not to talk about the menstruation taboos with a long list of ‘dos’ and ‘don’ts’ that women across the nation continue to face, such a campaign was bound to (and meant to) provoke. Students wrote messages against rape culture, gender violence, menstruation taboos on sanitary napkins and put them in various places around the campus and some other places. While the administration in Jamia was quick to remove the pads, it did GET many people talking.

The campaign tried to rope in a number of issues ranging from the attitudinal problem with regard to rape, the stigma attached to menstruating women being impure, the superstitions that put in place absurd practices of segregation during menstruation. The aim of using sanitary napkins for this purpose was to add shock value and shake the society from its drunken stupor of being complacent when it came to issue of sexual harassment of women. It’s the very discomfort and disgust with menstrual blood which renders it with subversive capacity. Many of us had heard about republican women held in Armagh Women’s Prison used menstrual blood as a means of resistance in their political struggle against the state.

What enrages many activists is that society seems to be more disgusted with menstruation than with gendered violence. The disgust around this natural body function is extremely strong. Menstruation is dirty. A menstruating girl is a polluting thing—a thing to be feared and shunned. Restrictions on food habits, mobility etc which defy all kind of logic is applied. The discomfort and pain which a woman goes through is however not even acknowledged. Cramps are to be borne without complaint. It was to address this varied issues that the campaign was initiated.

It met with mixed response. And the social media was awash with various views on the same. While the university of Jamia did not take too kindly to the campaign, it is the response of the larger student community which is interesting. The university issued a show cause notice to the campaigners. The administration very candidly puts that they are not opposed to the message being spread against sexual harassment but the means used. This ironically re-entrenches the disgust that people feel with menstruation. In this campaign the means used was as important as the message. Jamia being a minority institution saw some heated response from students of the minority community as well.

Leaving aside questions of theological nature, of what religions had to say about the purity/impurity status of a menstruating woman, many had other problems with the campaign. Many liberal men who claimed to be all for gender equality felt that the movement did not address issues of rape which is a bigger problem than the stigma attached to menstruation. The violence and trauma that rape victims and survivors go through is not addressed in this campaign because it focuses more on menstruation. This became the basis of dismissal for many. Campaigners however pointed out that the campaign also encompassed issues of rape and gender violence. Moreover menstruation taboos which dehumanizes women on a regular day to day basis, treats women as an untouchable is also an issue that needs to be talked of. The shame attached to a natural biological phenomenon is absurd. Women have been frisked, forced to GET down of buses because they are menstruating. So the stigma needs to be countered.

For many others the campaign is silly and not about feminism. Why something a woman goes through every month could be dismissed so casually by people claiming to be feminists and sympathizers, one needs to wonder. Still some others felt that it leaves out a large number of rural women who are not sanitary napkin users. There is a tendency to overlook the fact that the inaccessibility of rural women to sanitary napkins could also be highlighted through such a campaign. They are often the worst victims of menstruation taboos. The entire idea was to START a dialogue about this issue, get people talking about the multiple facets of menstruation and accept it as a normal biological process.

Many were left uncomfortable for university campuses being used for such a campaign. But where else if not in universities? Should not university campuses give students the space to express their views, to take a stand in issues of socio-political importance? Universities must prepare students to intervene in society armed with progressive ideas. This campaign have set the ball rolling. Irrespective of their stand, it got people talking about menstruation publicly.

The nation is not unfamiliar to unique movements and campaigns. Be it the naked protest of women in Manipur against the rape of Thangjam Manorama, the decade long hunger strike of Irom Sharmila or this campaign of writing on sanitary napkins – such movements despite limitations and shortcomings will continue to set the discourse for issues which are left out in the mainstream or challenge set norms.

No comments:

Post a Comment