Cheryl Crisp

The National Heart Foundation last week released “Heart Maps” of hospital admissions due to heart disease, the first such Australia-wide report of its kind. The maps expose a health gulf between the wealthiest areas of the country and the poorest, as well as the impact that poverty, unemployment and lack of medical facilities have on health outcomes.

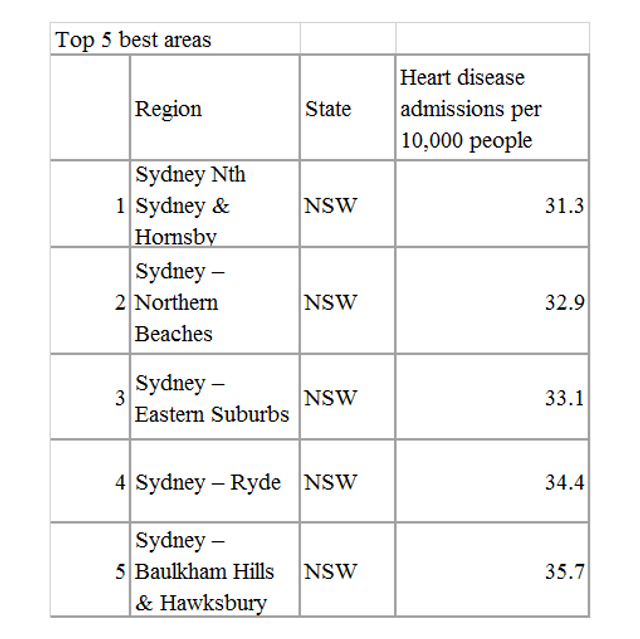

There is about a five-fold difference between the area with the highest rate of hospital admissions, the Northern Territory (NT) outback, and those with the lowest rates, situated in the most affluent suburbs of Sydney. The NT outback covers some of the most remote parts of Australia, furthest from metropolitan and regional cities.

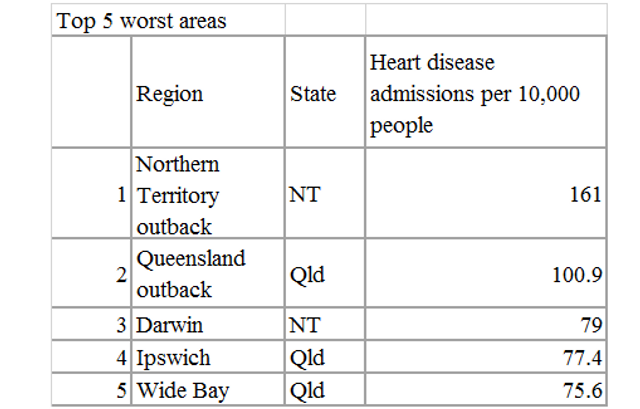

After the NT outback, which has an aged-standardised rate (ASR) of 161 admissions per 10,000 people, the next worst region is the neighbouring Queensland outback, followed by Darwin, the NT capital, and two areas north and west of the Queensland capital of Brisbane. Queensland recorded 12 of the worst 20 areas in the country.

Heart Foundation CEO John Kelly stated: “Those regions that rate in the top hotspot areas are regions where a large proportion of residents are of significant disadvantage. This disadvantage includes a person’s access to education, employment, housing, transport, affordable healthy food and social support.”

Overall, the report concluded that people in the “most disadvantaged areas are more than twice as likely to be admitted to hospital for a heart event than those living in the most advantaged areas.”

The Heart Maps display hospital separation data for two years (2012–13 and 2013–14), with a separation defined as a completed episode of patient care in hospital resulting in discharge, death, transfer or change in type of care (e.g. acute to rehabilitation.) The maps cover “All Heart Admissions,” including heart attacks, both STEMI and Non-STEMI.

STEMI is a severe form of heart attack caused by a significant or complete blockage of a coronary artery that results in full thickness damage to the heart muscle. Non-STEMI attacks, caused by a partial blockage of a coronary artery, result in less damage to the heart. The report does not include people who died of heart-related disease before they reached hospital.

In part, the report focusses on the impact of remoteness and the related issue of higher heart disease admissions among indigenous people, who make up a substantial part of the remote population.

According to the report, “the further a person lives from a major city the greater the rate of heart-related hospitalisations.” People living in a very remote area are almost twice as likely to visit a hospital for a heart event.

The report adds: “Along with higher rates of smoking, obesity and physical inactivity, remote Australia experiences higher levels of disadvantage, has poorer access to health services and the conditions needed for health such as an environment that supports physical activity, access to affordable healthy food, access to education and secure employment.”

Moreover, “Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander peoples are two and a half times more likely to be admitted to hospital for heart events that non-Indigenous Australians.” For all separations, indigenous people have an admission rate of 117.9 per 100,000, compared to the non-Indigenous average of 48.9.

But the divide is not simply geographical or racial. It is essentially a class chasm. The working-class city of Ipswich, with a population of almost 200,000, has the fourth highest rate in Australia, even though it is less than 40 kms from the centre of Brisbane. Wide Bay, the fifth highest area, covers the coastal towns of Bundaberg, Maryborough and Gympie, just north of Brisbane.

Ipswich has an official unemployment rate of 10.3 percent—almost double the national rate of 5.7 percent. Wide Bay has a jobless rate of 9.5 percent, while the Queensland outback rate is even higher, at 13 percent. These figures, which exclude people working more than an hour a week, seriously underestimate the real levels of unemployment

By contrast, all the areas recording the lowest hospital admission rates are among the most expensive suburbs nationally in terms of housing prices and median income levels. “Sydney – Eastern Suburbs” includes Point Piper, Australia’s richest enclave, which falls within Prime Minister Malcolm Turnbull’s electorate of Wentworth. Point Piper has a median house price of almost $9.5 million.

According to the Australian Tax Office’s Taxation Statistics 2013–14, those residing in Australia’s richest postcode, which also includes Edgecliff and Darling Point, reported taxable incomes averaging $200,015 per year. The tax returns submitted in the poorest postcodes in the Queensland outback, had an average income of just $3,196—some 62 times less than the wealthiest postcode.

Professor Kelly refuted the often-stated myth that individuals simply make bad “lifestyle choices” about what they eat and how much activity they carry out, and therefore bear the sole responsibility for their health outcomes. Such assertions serve as justifications for slashing health funding, on the basis that society should not be burdened by the cost of health care for these people.

Kelly pointed to the pervasive impact of poverty on people’s lives. He noted: “These higher rates [of admissions] are not because poor people make unhealthy choices. They are the result of social, economic and physical conditions, like a person’s access to education, employment, housing, transport, affordable healthy food and social support…. These conditions shape matters such as people’s eating habits, participation in physical activity and their likelihood to see a doctor.”

Kelly added: “According to projections, we know that these inequities in heart health will only worsen as the gap between the rich and the poor widens… We all have a responsibility to take care of our own health, but it isn’t right when things outside our control impact on our heart health.”

With heart disease still the leading cause of death for both men and women nationally—15.6 percent and 13.7 percent respectively—the report is a damning indictment of the social conditions that working class people experience in Australia, for all the references to it being the “lucky country.”

Kelly implored governments, other sectors and health services to “work together” to improve access and opportunities for good health, in the hope that the stark figures contained in the report will shame governments into providing the resources necessary to turn around this dire situation.

The reality, however, is that successive governments, federal and state, Labor and Liberal-National alike, have cut public health spending, widening the social and class gap. National expenditure on health fell from 18.09 percent of total government outlays in 2006–07, when the last federal Labor government took office, to 15.97 percent by 2015–16. This has intensified the creation of a two-class health system, with profitable private clinics and hospitals flourishing alongside chronically-underfunded and over-stretched public hospitals.

The health divide documented in the Heart Maps is a product of the corporate assault on essential social services and working and living conditions that confronts working people throughout Australia and internationally.

No comments:

Post a Comment