Debra Watson

The recent severe cold spell in large parts of the US will be remembered most due to the frequent reports of homeless citizens freezing to death, because they could not find housing, or even emergency shelter. Half a million homelessness are living on the streets of major US cities this winter, according to official counts.

Millions more face a precarious housing situation, threatened not only by a lost job or illness, events that often lead to a foreclosure or eviction, but a general decline in living standards related to widening income inequality in the US.

Precipitous increases in rent and stagnant and declining wages are creating an unsustainable squeeze on lower income households. The number of those who must spend the majority of their monthly income on rent is rising and along with that the portion of the monthly income they spend on rent is rising too.

A December report on the housing crisis that appeared in a publication of the Board of Governors of the US Federal Reserve, called FEDS Notes, reports on the distress for families in the lowest US income quintile brought on by a squeeze in monthly income from rising rents and stagnant or falling wages.

In general, these families earn under $25,000 annually. The lowest-paid fifth of US households includes workers making more than minimum wage. In Michigan a minimum wage job for a worker employed every week for the whole year yields about $18,000. Rent increases have rapidly and relentlessly outstripped stagnant or declining annual wages for workers at the lowest income levels.

Written by researchers from the US Federal Reserve and the Brookings Institution, the December report notes that the portion of monthly income that low-income households must spend on rent has been rising through the last several business cycles. “Rent burdens have increased over the past 15 years, due to both increasing rents and decreasing incomes,” they say.

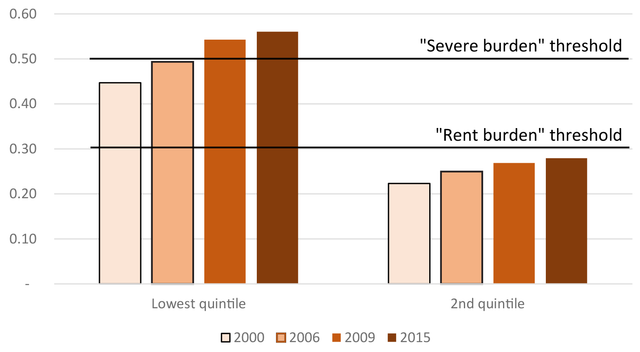

The squeeze is relentless. Families at the bottom end of the pay scale have not been able to get out of the squeeze in the business recovery after a recession. They note: “This increase in rent burdens over the past 15 years occurred through each business cycle period including both the period prior to the financial crisis (2000-2006), the economic downturn (2006-2009) and the subsequent recovery (2009-2015). Although rent-to income ratios are greatest among low-income households, the share of income spent on rent also rose among higher income renters.”

They also explain the main economic sources of the plight of low-income renters: “Of the overall decline in residual income since 2000, around two-thirds came from declines in income among renters and one third resulted from rising rents.”

The FEDS Notes release in late December used statistics from the US Census Bureau American Community Survey. Their report provides a window into the desperate circumstances working class families, especially those at the low end of the income scale, now face when seeking housing.

They note the deterioration of renter family’s ability to cope with the ever-rising rents. “The median renter in the lowest income quintile pays 56 percent of monthly income on rent,” exceeding HUD’s standard for rent burdened, paying more than 30 percent of income on rent and severe rent burdened, paying more than half of income for rent. “Though the rent burden has increased at every income level, it is especially acute at the lower end of the US income scale,” they say.

“Such renters have little left for paying everything else,” according to the report. “In the lowest income quintile in the US a family has just $476 left after housing costs for all other basic needs,” noting Census bureau estimates that a family needs nearly three times this—$1,400—for these basic needs.

Last fall Freddie Mac Multifamily presented detail that throws light on the trend of rising rents. Researchers there noted how rapidly rents in multi-family units they finance are going up. Increases on rents on existing properties in apartments were squeezing low-income renters, following a general trend in US rental housing reported elsewhere by housing advocacy groups.

The Federal Mortgage Home Loan Corporation (FMHLC) or Freddie Mac, is one of two major US housing finance entities, along with Fannie Mae.

Some sixty to eighty percent of affordable rental apartments in privately owned multi-family apartment buildings financed by mortgage lender Freddie Mac have been eliminated in the US since 2010.

Very low income households, used in the Freddie Mac report, are defined for various US government agencies as families making half or less than the median income in a particular geographical area. This is a step above HUD’s Extremely Low Income designation, and falls in the same range as the lowest quintile households covered in the FEDS Notes report.

In the Detroit metropolitan area in 2016, very low income was about $24,000 for an individual renter. By comparison, extremely low income individuals have annual incomes of about $14,000.

Along with a dearth of building in the low-income rental market—most new apartments are built and command rents only affordable to the much better off—the report notes that housing construction costs are also a factor and have been exacerbated by the hurricane destruction in Texas, Florida and Puerto Rico.

Freddie Mac researchers compiled figures back to 2010 on lending to multi-family projects, that is apartment buildings they financed twice during that period: “[W]e analyzed the affordability of the exact same units at two different, but close, points in time.”

Families denoted as VLI necessarily had not moved out as rents increased year by year. Instead the same population living in the buildings ended up paying what amount to unsustainable housing costs, paying rents exceeding the HUD affordability benchmark.

The Freddie Mac researchers used two sets of data to look into affordable housing for very low income renters. The first used internal numbers on a relatively small set of data to examine how it compared with overall trends in rental housing adversely impacting lowest income renters being reported elsewhere.

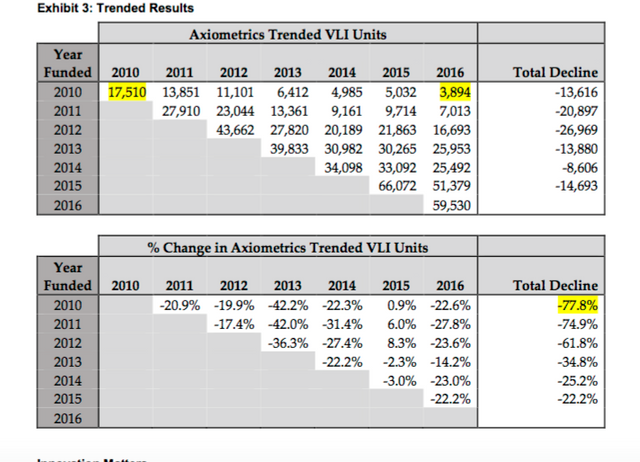

In the 97,000 rental units in multi-family buildings Freddie Mac financed in 2010 and then again in 2016, the percentage of units affordable for very low income households dropped by more than half, from 11.2 percent to 4.3 percent nationwide. These were refinances of the exact same units.

Some states were hit hard. For example, in Colorado in 2010 about a third—32 percent of the 5,100 rental apartments financed with Freddie Mac loans were affordable for very low income households. By 2016 the same buildings were re-financed by the agency and only 7.5 percent of the very same apartments were VLI affordable.

An expanded part of their analysis looked at all multi-family housing projects they originated from 2010 to 2016 and found an even greater decline of 78 percent between 2010 and 2016 of apartments deemed affordable to very low-income renters when Freddie Mac lent to the owners. Rent increases had wiped out affordability at tens of thousands of units by 2016.

It is remarkable that warnings usually heard from housing agencies and advocacy groups—that is groups dedicated to advocating for the vulnerable—are the subject of earnest reports advanced by financial entities at the commanding heights of the US economy. The Federal Reserve is a key player in fueling the general investment frenzy leading to the stock market rise and contributing to driving up rents.

The few solutions being offered are less than inadequate. Freddie Mac indicates in its report that one approach to addressing the problem is to look to financing manufactured homes—that is, into one of the most dangerous housing options one can find! This parallels the sclerotic federal and state efforts, often advanced by sections of the Democratic Party, to provide funding for assistance. Even existing programs, woefully underfunded, face decimation under the Trump administration to pay for tax cuts to the wealthy.

No comments:

Post a Comment