Richard Phillips

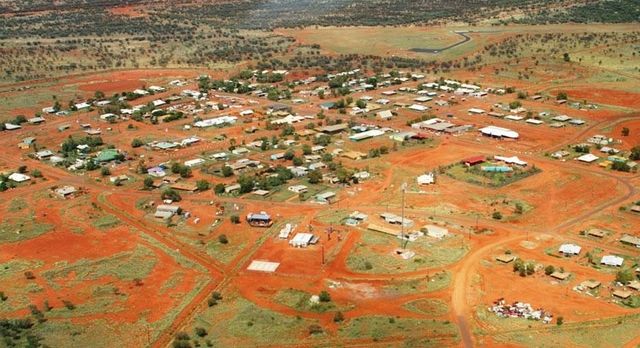

Last month’s death of 19-year-old Kumanjayi Walker after being shot by police in Yuendumu is an inevitable product of ongoing government spending cuts and escalating police-state style repression of poverty-stricken Aboriginal communities. Yuendumu is a remote community about 300 kilometres northwest of Alice Springs in the Northern Territory (NT).

According to police, Walker was wanted for “outstanding offences.” He was shot three times inside his grandmother’s home at about 7.15 p.m. on November 9.

There will be a coroner’s inquest into Walker’s death, along with a NT Independent Commission Against Corruption inquiry, an internal police probe and a police professional standards investigation. However, all previous official inquiries into “deaths in custody” have exonerated police.

There have been over 425 recorded Aboriginal deaths in custody since the Hawke Labor government’s 1987–91 royal commission into such killings, including 18 since August last year.

After being shot, the severely wounded Walker was taken to the Yuendumu police station where he is believed to have bled to death about two hours later, without receiving professional emergency care. The under-resourced local health clinic was not open at the time. NT health authorities had ordered medical staff to leave the area a day before.

Yuendumu in central Australia

Yuendumu in central Australia

Authorities claim the clinic’s staff had left because they feared burglaries. Whether this is true or not, government funding to remote community health and other basic social services has been systemically run down for more than a decade.

In October, the NT Labor government announced that clinics in the remote communities of Alcoota, Epenarra, Haasts Bluff and Yuelamu would be closed from mid-December, forcing residents to travel up to four hours for emergency health care. While the NT government, following Walker’s death, declared that the clinics would not close, residents are rightly suspicious that the reprieve is a temporary political manoeuvre.

Constable Zachary Rolfe, 28, a former Australian Army soldier and Afghanistan veteran, was charged with murder and quickly granted bail, following a special overnight phone hearing with the on-call judge on November 13. He has been suspended on full pay and permitted to travel outside the NT.

Procedural hearings on the murder case will be held on December 12 and 19 in Alice Springs to decide whether the trial should be heard in Alice Springs or Darwin and when it will begin. The Police Federation of Australia has condemned the charging of Rolfe as deleterious to “police morale.”

Northern Territory Supreme Court in Alice Springs

Northern Territory Supreme Court in Alice Springs

The immediate response of the NT police to the November 9 shooting was to provocatively dispatch 40 members of its Territory Response Group (TPG) to Yuendumu, which has about 700 residents. The TPG is a heavily-armed, military camouflage-wearing unit. Its officers are armed with Remington R5 rifles or Sig Sauer 716 semi-automatic weapons.

Frank Baarda, a long-time resident who writes a local news blog—“Musical Despatches from the Front”—described the mobilisation as “an organised display of force” and the “largest concentration of armed police” he had seen since visiting Mexico during the suppression of student protests in 1971.

“Why the overt display of weaponry?” Baarda asked on his blog. “Was it out of unwarranted fear? Or was it an insensitive display resulting from ignorance or arrogance or both?… Bureaucrats politicians and the media are complicit in spreading misinformation, which is once against portraying Yuendumu as this incredibly unsafe and dangerous place.”

On November 21, right-wing commentator Andrew Bolt published an inflammatory comment in the Murdoch-owned Daily Telegraph entitled, “Was Constable Rolfe charged with being white?” Bolt insisted that a crowd of peaceful protestors in Yuendumu were being “primed for another riot” and inferred that Rolfe would not be given a fair trial. “Is justice being done? Or do I smell politics and the new tribalism?”

Five days after Walker’s death, and following protests across Australia, including a more than 1,000-strong demonstration in Alice Springs, Minister for Indigenous Australians Ken Wyatt met with Yuendumu community leaders.

Part of the November 14 protest in Alice Springs

Part of the November 14 protest in Alice Springs

The Yuendumu elders are demanding the removal of armed police from their community, and other remote settlements, and called for support from Wyatt, the first Aboriginal to be appointed the Minister for Indigenous Australians. He refused to comment.

“He’s our representative, he’s a federal person, he should have given me something, but I wasn’t satisfied with his comments and with the way he was talking to me,” Ned Hargraves, one of the elders, told NTIV News.

Ned Hargraves

Ned Hargraves

Yuendumu residents cannot “trust anybody right now,” Hargraves said. “We can’t trust the police. They are saying, ‘We are for you, we serve the country, we serve you, we protect you,’ [but] where is the protection for us? We are weeping. We are not happy with the whole situation.”

The day after the meeting with Wyatt, NT Chief Minister Michael Gunner declared that his Labor government would support all the “operational decisions” of the police. In other words, the repression and provocations would continue.

Nine days after Walker’s death, a 23-year-old Aboriginal man was hit by an unmarked police car and seriously injured on November 18 in Alice Springs. NT Police allege that he was armed with a knife and attempted to get away from officers who chased him on foot and in vehicles. Police told the media “the serious custody incident” would be investigated internally.

Over the past 12 years, Aboriginal communities in the NT have been the target of a sustained political assault—first by the federal Liberal-National Coalition government’s Northern Territory Intervention and then the Rudd and Gillard Labor government’s “Stronger Futures” program.

Thousands of Aboriginal workers and their families suffer horrendous poverty—unable to access decent housing, education, transport, safe drinking water and other rudimentary social needs—while millions of dollars are handed out to the police, the judiciary and other components of the state apparatus.

This is symbolised in Alice Springs by the recently completed $14 million NT Supreme Court, which towers over the city’s small shopping precinct.

In Yuendumu, where, according to recent figures, 52 percent of the working-age population is unemployed, residents suffer substandard and overcrowded housing, poorly-resourced schools and inadequate social facilities. The largest single amount of government money ever spent in the community was for a new $7.6 million police station.

With about 30 percent of its population being indigenous, the NT is Australia’s most heavily-policed state or territory. It has almost 700 police per 100,000 population—2.6 times more than the national average. The NT Southern Command, which covers the central Australia region, has three times the national average.

Aboriginal people confront scores of reactionary, anti-democratic measures, including mandatory sentencing laws for a range of social crimes.

Police have sweeping powers to raid people in their homes without search warrants and arrest individuals for so-called anti-social conduct. This year the NT government introduced a special app for reporting such behaviour.

Paperless arrest laws, introduced in 2014, give the police powers to arrest and detain a person for four hours, or, if deemed to be intoxicated, “for as long as they are judged to no longer be intoxicated.” Over 1,295 people were taken into custody in the first seven months after these laws were introduced, almost 80 percent of them Aboriginal people.

Police auxiliary liquor inspectors in Alice Springs supermarket

Police auxiliary liquor inspectors in Alice Springs supermarket

Last year, the NT government introduced a “police auxiliary liquor inspectors” program, employing over 100 officers. The armed police are stationed outside all stores selling alcohol and check all purchases. Aboriginal people are systematically targeted with fines and arrests.

Tangentyere Council CEO Walter Shaw, who lives in Mount Nancy, one of Alice Spring’s town camps, is currently taking anti-discrimination action against police over an incident in September.

Walter Shaw

Walter Shaw

After being blocked by police from purchasing a bottle of wine to have with dinner at a friend’s home in Alice Springs, Shaw requested a senior police officer come to the local bottle shop.

Senior police officers followed him and his wife to their friend’s house, and later back to his home, where they demanded to search his car. Confronted with Shaw’s barking dog, they responded by pepper-spraying the animal in full view of Shaw’s distraught children.

“I must be the only CEO in the world that’s been subjected to this. I’m a bit conflicted about taking legal action because there are Aboriginal people being treated far worse than me,” he told the WSWS last week.

“I can understand why a lot of Aboriginal people, particularly here in the Northern Territory, where authorities flout their basic rights and where they’re racially profiled, vilified and discriminated against, would be reluctant to challenge the authorities. The difficulties of steering your way through this are overwhelming—even the common person wouldn’t know how to navigate this repressive system—but there’s an issue of principle here.”

No comments:

Post a Comment