Cesar Uco

Hundreds of students from the Universidad Alas Peruanas (UAP) protested on February 7 in the southern Peruvian city of Arequipa against a state education agency’s revocation of the university’s license which threatens to curtail their educational careers.

The demonstrators stabbed their arms with syringes until they bled and bound themselves with chains outside Arequipa’s Municipal Theater, where Peruvian President Martín Vizcarra was scheduled to speak. When the students tried to move towards the theater, they were pushed back by a phalanx of police equipped with riot shields.

The protest was the latest in a series of demonstrations by students from private, for-profit universities which have had their licenses revoked by the National Superintendency of Higher University Education (in Spanish, Sunedu) for failure to meet basic educational standards. Some 39 private universities and 116,000 students are affected. The institutions have been ordered to stop admitting new students and close down within one year.

Universidad Alas Peruanas main center in Jesus Maria, Lima

Universidad Alas Peruanas main center in Jesus Maria, Lima

The students’ main demand is that the private institutions be treated the same as public universities denied their licenses, which are given a two-year grace period to remedy their deficiencies.

While the government has stated that the students can go to national public universities or transfer to other private universities, there is not enough space in the public institutions and more expensive private schools are out of reach for many who come from families with low incomes.

“This is a moment of uncertainty,” Gianpol, an administration student from UAP, the largest of the affected schools, with 65,000 students, told the World Socialist Web Site. “We were not told anything about the process of how universities were denied [licenses]. Many young people still don’t know what to do, what college to go to or what colleges they can afford.” He added that students were concerned over whether other colleges would accept their credits from a school shut down by the government and over likely increased tuition costs.

“There are certainly businessmen linked to the education sector who are taking advantage of youth with less resources, profiting from young people,” Gianpol said. “There is inequality, since we all have the right to study. Whether you’re poor or rich, the state should take care of it. Education is very important not only for your professional life but serves to develop you as a person, as a human being and grow as citizens, to do things better, to change society.”

Beginning in 2016, the Ministry of Education, through its subsidiary Sunedu, initiated an evaluation of Peruvian universities. What it found were gross violations of Basic Quality Conditions (in Spanish, CBC) established under the national university law, as well as fraud and corruption by businessmen seeking to exploit the striving for an education by some of the country’s more oppressed social layers.

A total of 37 universities (90 per cent of those denied licenses) were founded based upon the free market policies imposed by the IMF in the early 1990s under the dictatorship of President Alberto Fujimori as a condition for having access to international financial markets.

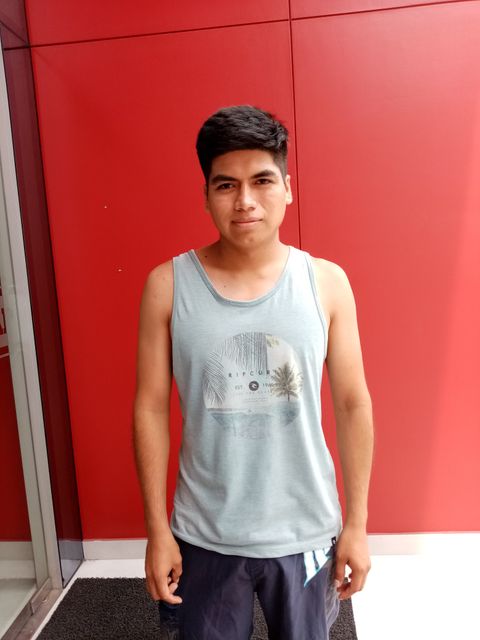

Ginapol a student of management at Universidad Alas Peruanas that has been ordered by the government to close down within one year

Ginapol a student of management at Universidad Alas Peruanas that has been ordered by the government to close down within one year

Thirty-five of the private for-profit universities threatened with shutdown have been established since 2000, their emergence coinciding with the investment of tens of billions of dollars by transnational mining companies in the exploitation of Peru’s natural resources.

The mining boom from 2002 to 2014, which saw GDP growth of 6.1 percent per year, produced a reduction in poverty and extreme poverty, creating a demand for higher education among lower-income families.

With the decline in the demand for mineral resources and economic growth beginning in 2015, however, unemployment rose and consumption shrank, with the private education sector one of the first to be affected.

Two overlapping phenomena are present in Peru university crisis. The first has to do with most universities being denied for not meeting the eight CBC requirements. The other is one of corruption involving two of the three largest universities threatened with shutdown.

In 2018, the Inca Garcilaso de la Vega University, with16,000 students, paid dean Luis Cervantes and his small clique of teachers an amount of 43.5 million nuevos soles (US$13.2 million) in “golden salaries”, the Peruvian daily La República reported.

Alas Peruanas, with 65,000 students, was founded in 1996 by Fidel Ramírez together with an Air Force officers’ association. It was linked by the US Drug Enforcement Administration (DEA) to drug trafficking and money laundering, with UAP planes allegedly used to transport drugs to Miami. Ramírez’s nephew, Joaquín Ramírez, was a congressman and secretary general of the right-wing fujimorista Fuerza Popular party, charged with laundering bribe money for the party’s now imprisoned leader Keiko Fujimori.

The remaining 36 universities had a combined student body of just 16,000 students, an average of 445 students per school. San Francisco Xavier Graduate School, in the city of Arequipa, had just 17 students, four classrooms and 12 teachers (mostly part-time), yet offered four master’s degrees and a doctorate.

In the face of the mounting crisis and protests, President Vizcarra made 18 million nuevos soles—US$ 5.5 million—available for national universities to admit low-income students from the private schools who, otherwise, would be on the streets.

The fear within the government and the Peruvian ruling class is that anger among youth at the exploitation and inequality that pervades Peru’s society and its educational system can be the spark that ignites the kind of social upheavals that have gripped Chile, Ecuador and Colombia in recent months.

No comments:

Post a Comment