Benjamin Mateus

On December 31, 2019, Wuhan’s Health Commission notified the World Health Organization (WHO) Country Office of cases of pneumonia-like illness of unknown etiology. At the time, there were forty-one cases, of which 11 were severely ill. The next day the WHO requested additional information from the Chinese authorities to determine the risk of community transmission.

On January 7, Chinese authorities identify the pathogen causing these illnesses as a novel coronavirus, implying that the virus had a pandemic potential because no one on the planet would have immunity to it. A few days later, the genomic sequence for the virus was uploaded into the GenBank sequence database and shared with the world. On January 11, Xinhua News Agency reported the death of an ailing elderly man with health issues who succumbed to complications from the infection. Since then, over the four months that have passed, more than 4 million people across the globe have become infected, and 275,000 have perished.

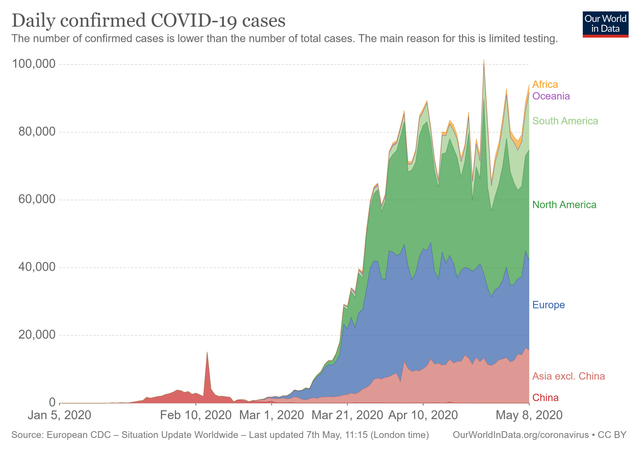

Though the pandemic has impacted 212 countries and territories, the real brunt of the health crisis hit the European countries and the United States hardest. Adequately forewarned but least prepared, they squandered the weeks after the declaration of an international emergency by the WHO in late January. The initial months of the epidemic in China now seem to pale in comparison when in late February to mid-March, the virus began to take its toll rapidly.

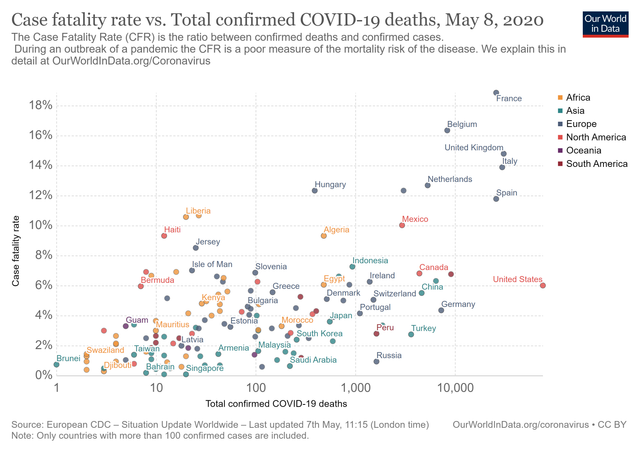

According to the website Our World in Data, Belgium has had 726 deaths per million, Spain with 558, Italy with 495, the United Kingdom with 451, France with 398, Netherlands 309, Sweden 301, and the United States with 229. China, by comparison, has little more than three deaths per million.

Yet, by all accounts, these fatality reports are underestimations. As health care systems in these countries reached near collapse, the necessary accounting of cases lagged or completely missed them. Many were turned away from hospitals only to perish at home, infecting those that had to care for them, fueling the transmission of the pandemic deeper into communities. The Financial Times, based on their analysis of overall fatalities and excess deaths, placed the toll from COVID-19 sixty percent higher than official counts.

Presently, the seven-day rolling average of new deaths stands at 1,723 average deaths for the United States and 568 average deaths for the United Kingdom. These curves show plateauing or downturning. These are true for Italy, Spain, and France as well, though all three nations still have deaths over 100 per day. Countries with worrisome trends include Brazil, with increasing trends approaching 500 deaths per day with a doubling time of almost seven days. Canada is closing on 200 deaths per day as it continues to climb steadily. Russia’s death tolls are demonstrating a rising trajectory. However, their absolute numbers are still quite low in comparison to their daily case rates, which is now only second to the United States. Russia has exceeded the US in per capita testing.

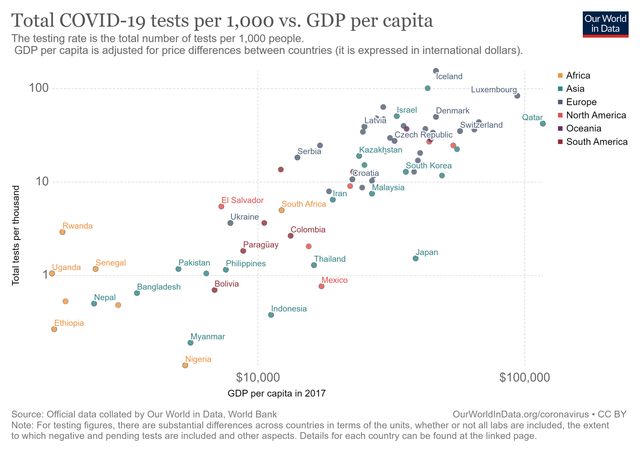

India, Peru, and Ecuador also see daily new cases and fatalities climb. Yet, they have some of the lowest testing per capita. For Ecuador, despite small numbers of reported daily deaths, these appear to be gross underestimations. According to the Financial Times, with only 245 official COVID-19-related deaths in Guayas Province that were published between March 1 and April 15, their analysis showed that there were 10,200 excess deaths during this period compared to previous years—a more than 350 percent increase.

The number of cases and fatalities has disproportionately impacted upper-middle and high-income nations. However, this is a byproduct of how the virus was transmitted across the globe through commercial air traffic directly to these cities. Phylogenetic studies of the virus have intricately traced the spread of the virus to various major cities in Europe and the United States. Yet, within these high-income countries, it is the poorest in these large populated metropolitan areas, dense urban centers, that suffer the highest case fatalities. Presently, New York City, Chicago and Los Angeles remain vectors for the pandemic in the United States.

As the WHO has repeatedly noted, the pandemic is in its early stages. As the major cities of producing nations are bringing the epidemic under some measure of control, the pandemic has begun to move regionally. These include Eastern Europe, the Indian subcontinent, the Americas, and Africa. These regions also boast the lowest income per capita. Without a robust testing capacity, these regions could be in a similar predicament as Europe and the US as the virus silently ravages through communities. The economic toll due to the massive contraction of global markets will be hardest felt in the regions that lack the financial resources to meet basic medical needs and social infrastructure.

In the early part of April, Oxfam published a report warning that the economic fallout from the COVID-19 pandemic could very well push half a billion more people into poverty unless urgent action was taken by producing nations to “bail out” developing countries. More than three billion people are living in poverty, and 25 percent of the globe suffer from food insecurity. “But for poor people in emerging countries who are already struggling to survive, there are almost no safety nets to stop them from falling into poverty.”

These sentiments will fall on deaf ears of the financial oligarchs. Despite the record job losses in the US where data showed 20.5 million jobs lost in April and almost 15 percent of the US unemployed, the Dow Jones climbed 455.43 points to close at 24,331.32. As Kristina Hooper, chief global market strategist at Invesco, said, “Stocks have decoupled from the economy.” The Financial Times highlights the “swift actions from the Federal Reserve, the European Central Bank and the Bank of Japan” has continued to bail out the markets and to commit to buying “an unlimited quantity of government securities.” These measures are working in concert with the states to force workers back to their place of employment regardless of the risk being posed. These will ignite second waves of the pandemic, as has been evidenced by developments in meatpacking industries.

Africa remains, by comparison, less affected by the pandemic. With 58,361 cases across the continent and only 2,140 deaths, they saw only 57 new fatalities yesterday, predominately in Egypt and South Africa. However, in a study by the WHO Regional Office for Africa, they found that if containment measures fail, they project that 83,000 to 190,000 people could perish, and 29 to 44 million could be infected in the first year of the pandemic.

The lower fatality and infection rates on their estimates take account of the unique social and environmental factors in Africa slowing the transmission. The lower rates of transmission also mean there will be a prolonged outbreak that may last years, remaining as a smoldering hotspot for future regional and worldwide outbreaks. The number of people afflicted by the infection would certainly strain and overwhelm the health capacities of these nations.

No comments:

Post a Comment