Dietmar Gaisenkersting

Almost 40 years after the Oktoberfest bombing, the Federal Prosecutor’s Office in Karlsruhe is officially discontinuing the investigative proceedings, which were resumed in 2014. It admits for the first time that the assassin, Gundolf Köhler, was a right-wing radical who killed for political reasons. But that was hard to deny after all that is known.

The intention is to keep the public in the dark forever on the background to the killings and the people behind it, especially the role of the security services, above all the federal Office for the Protection of the Constitution (Verfassungsschutz), as the secret service is known.

The Oktoberfest bombing was the most serious right-wing terrorist attack in the history of the Federal Republic of Germany. The bomb was placed in a wastebasket by Köhler on the evening of September 26, 1980. It killed 12 Oktoberfest visitors in Munich as well as the perpetrator. Two hundred and eleven people were injured, some of them seriously.

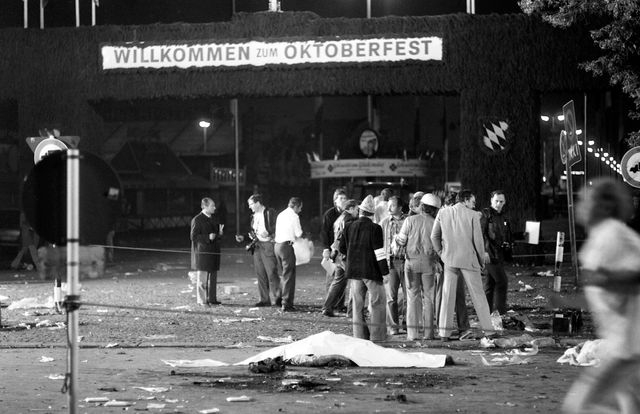

Victims of the attack at the crime scene in front of the main entrance to the Oktoberfest (AP Photo/Dieter Endlicher, FILE)

Victims of the attack at the crime scene in front of the main entrance to the Oktoberfest (AP Photo/Dieter Endlicher, FILE)

At the time, the investigating authorities covered up the neo-Nazi and right-wing terrorist background of the assassin. Witness statements, according to which Köhler was not alone on the evening of the attack, were ignored. The thesis of a sole perpetrator was quickly the established narrative.

Köhler, who was a member of the right-wing extremist Wehrsportgruppe (military sports group) Hoffmann, and who had a picture of Hitler hanging over his bed, was said to have built and detonated the bomb out of distress and frustration over a failed exam. The terror attack was labelled the homicide-suicide of an unbalanced and suffering student. Some two years after the bombing, in November 1982, the federal prosecutor general ended the investigation.

Journalist Ulrich Chaussy and the victims’ attorney Werner Dietrich never accepted the official narrative and spent decades doing their own research. Thanks to their work, the Federal Prosecutor’s Office was forced to reopen the case at the end of 2014. But last year, the “26 September” special commission of the Bavarian State Office of Criminal Investigation was dissolved.

“The perpetrator acted out of a right-wing extremist motivation,” a senior investigator told the Süddeutsche Zeitung. “Gundolf Koehler wanted to influence the 1980 federal elections,” the investigator continued. “He wanted a ‘Führer state’ based on the model of the Nazis.” The Christian Social Union (CSU) right-wing candidate for chancellor, Franz-Josef Strauss, was to benefit from this in the Bundestag (federal parliament) elections that followed shortly thereafter in the fall of 1980. “It was not a rampage without sense or reason,” an investigator told the Süddeutsche Zeitung.

In initial statements, attorney Dietrich and journalist Chaussy expressed relief that the public prosecutor’s office now considered the act a right-wing terrorist attack, because they believed that would make it possible for the victims to be compensated. Some 100 of the victims are still alive.

For decades, they had been spurned by the authorities and ridiculed as malingerers, despite having suffered life-long, in some cases very serious damage from bomb fragments. In 1980 alone, 58 people were listed as having had their legs amputated or suffered severe organ injuries. To this day, the Federal Office of Justice continues to deny the victims compensation from the fund for victims of terrorism and extremism.

It is now generally expected that the victims will be compensated, even though the federal government’s fund is obliged to compensate only victims of attacks committed after 1990. For attacks before that, it is stipulated that money will be paid only for “particularly serious incidents.” Even though the Oktoberfest attack meets this criterion, the victims will still have to fight for their compensation.

Regardless of the further course of victim compensation claims, the termination of the investigation has far-reaching political implications. It has one effect above all: the people behind the attack and the role of individual politicians and state authorities will remain in the dark.

The investigators once again interviewed more than 1,000 witnesses, pursued almost 800 new leads and sifted through more than 420,000 pages of new files from the West German and East German secret service apparatuses. “But it didn’t help,” wrote Der Spiegel. “The open questions surrounding the most devastating extreme right-wing terrorist attack in Germany to date will probably remain unanswered.” The Süddeutsche Zeitung advanced a similar line, writing: “The effort couldn’t heal the mistakes of the past.”

The investigations that followed the attack and the response of the secret services and federal governments over the past four decades were not “mistakes.” The first investigations from 1980 to 1982 had the goal of eliminating all references to Köhler’s right-wing extremist background, as well as to the Hoffmann military sports group, which the secret service had under observation. The thesis of a distressed individual perpetrator was no more plausible 40 years ago than it is today.

Subsequently, all traces and evidence that in retrospect could have been dangerous for right-wing extremists and the secret services were eliminated. For example, 48 cigarette butts were found in the ashtrays of Köhler’s car parked near the crime scene. They had already been destroyed in February 1981, half a year after the attack.

Investigators had found traces of three different blood groups on the butts of six different types of cigarettes, with and without filters. DNA could not be evaluated at that time.

The stubs were a clear indication that Köhler—as many witnesses had confirmed—had not traveled alone to Munich for the Oktoberfest. In later years, the DNA on the cigarette butts could have been used to identify Köhler’s passengers.

A torn-off hand, which could not be attributed to any of the known victims, was destroyed along with all other remaining evidence in 1997.

In 2014-2015, the federal coalition government, consisting of the Christian Democrats (Christian Democratic Union—CDU and Christian Social Union—CSU) and the Social Democrats (Social Democratic Party—SPD), refused to answer questions from the parliamentary opposition, which had demanded information about the findings of the Office for the Protection of the Constitution regarding the Oktoberfest bombing and Köhler’s right-wing extremist background provided by informers. In 2017, in response to an official complaint lodged by the Greens and the Left Party, the Federal Constitutional Court decided that the government had to answer only a few individual questions. The court allowed other important questions to go unanswered.

In 2015, Chaussy reported in an interview with the World Socialist Web Site that the investigators in the reopened proceedings were not willing “to enter into the necessary critical review of the investigations of their former colleagues.” According to the journalist, the 26 September Special Commission did not want to clear up the investigatory mishaps of the past.

Instead of revealing anything about possible backers and accomplices of the assassin Köhler, the investigators ignored all relevant leads. The witness whose testimony had played the key role in forcing the reopening of the case in 2014 was said to have simply made a mistake in her recollection of the timing of events.

Two of Köhler’s close friends were also re-interrogated by the investigators, as they had contradicted each other in 1980. The Federal Public Prosecutor’s Office came to the conclusion that, by all indications, they knew more than they had revealed, but that nothing more could be proven. The “involvement of other persons as accomplices, instigators or assistants in the crime,” the investigators said, could not be ruled out, but neither could it be proven.

The investigators also found an accomplice of the right-wing extremist forester Heinz Lembke, who was suspected of having supplied the explosives, but allegedly there was no connection to Köhler. It remains unclear whether Lembke worked for the secret service or other state agencies.

Attorney Dietrich discovered in files the note, “Findings about Lembke are only partially usable in court”—a formulation that normally occurs only in regard to Confidential Informants or secret service employees. Lembke was found hanged in his cell in 1981 after he had announced he would testify and provide detailed information.

The cover-up of the Oktoberfest bombing must be opposed. It is unacceptable that the secret service (Verfassungsschutz) escapes any control, functioning as a state within the state with the power to determine which of its files are handed over to investigators and which are not.

This writer read Lembke’s secret service file in the Federal Archives in Koblenz in 1998, at least the pages that were available. The most important pages in the file were clearly missing. The secret service had not handed over the pages to the relatively freely accessible archive.

The Verfassungsschutz and all such agencies must be abolished and dissolved. Their archives must be opened so that trustworthy persons—such as investigative journalists and serious scientists—can fully investigate the role and clandestine activities of the secret services and make them known to the general public.

No comments:

Post a Comment