Kate Randall

More than a half million people were homeless in the United States this year, nearly a quarter of them children, according to a new report. The homelessness crisis is a stark indicator of the social reality in 2015 America and corresponds to a scarcity of affordable housing and dwindling wages for low-income workers and their families.

The report from the US Department of Housing and Urban Development (HUD) released Thursday counted 564,708 people homeless, both sheltered and unsheltered. These figures, gathered by volunteers on a given night in January 2015, are undoubtedly an undercount. Many of those living in motels, doubling up with relatives and friends or living on the streets are likely not represented in the tally.

Twenty-three percent, or 127,787, of the nation’s homeless are children under the age of 18, according to HUD. However, this figure is at odds with statistics from another branch of the federal government. According to the Department of Education, there are 1.36 million homeless students in the nation’s K-12 public schools, double the number in 2006, before the onset of the financial collapse.

According to HUD, 206,286 people were in homeless families with children, or 36.5 percent of the HUD total. Six percent of these homeless families are chronically homeless, in which the head of household has a disability and has been homeless for a year, or has experienced at least four episodes of homelessness over the past three years.

The HUD figures show homelessness declining by 2 percent between 2014 and 2015. But even if these numbers are taken as good coin, this represents a minuscule decline that hardly makes a dent in the homeless population.

A homeless woman in Chicago—the number of unsheltered people with chronic patterns of homelessness increased in the past year for the first time since 2011

A homeless woman in Chicago—the number of unsheltered people with chronic patterns of homelessness increased in the past year for the first time since 2011

According to the National Alliance to End Homelessness, there is a shortage of 7 million units of affordable housing throughout the US, creating a desperate situation for workers and their families as they search for decent and affordable accommodations.

As the majority of working people feel the housing squeeze, they face declining real wages. According to a recent National Employment Law Projet report, workers’ wages have declined by 4 percent, after adjusting for inflation, between 2009 and 2014.

The vast majority of the US population has not experienced the benefits of the “economic recovery,” proclaimed by the Obama administration in mid-2009. Homelessness is one of the brutal consequences of these conditions.

Of the 564,708 people counted as homeless by HUD in January 2015, 69 percent were staying in sheltered locations, and 31 percent were unsheltered, living in places unfit for human habitation, such as under bridges, in cars or in abandoned buildings.

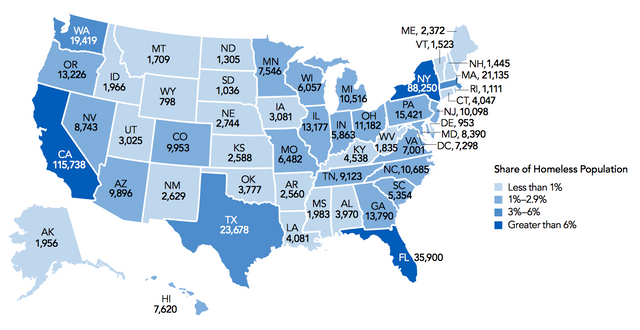

More than half of the homeless population is concentrated in five states:

· California: 21 percent or 115,738 people

· New York: 16 percent or 88,250 people

· Florida: 6 percent or 35,900 people

· Texas: 4 percent or 23,678 people

· Massachusetts: 4 percent or 21,135 people

While homelessness declined in 33 states and the District of Columbia between 2014 and 2015, according to the report, 17 states experienced an increase. New York State experienced an explosion of homelessness, rising by 7,660 people, or by 9.5 percent in one year. Since 2007, New York has seen a staggering 41 percent rise, with 25,649 people added to the homeless ranks.

More than one in five homeless people are located in the nation’s two largest urban areas: New York City, with 75,323 (14 percent of US total); Los Angeles (city and county), with 41,174 (7 percent). These are followed by Seattle/King County, Washington with 10,122; San Diego (city and county), 8,742; Las Vegas/Clark County, Nevada, 7,509; and the District of Columbia, 7,298.

Sixty-three percent of the homeless population are individuals without children. Of these 358,422 people, 57 percent were in emergency shelters, transitional housing programs, or safe havens. The remaining 43 percent were living rough—on the streets, in parks, abandoned buildings and vehicles. Most homeless individuals are men (72 percent).

Nine of every 10 homeless individuals are over 24 years of age. Fifty-four percent are white, while African Americans are disproportionately represented, accounting for 36 percent of the total. About 17 percent of homeless individuals are Hispanic or Latino.

HUD defines unaccompanied youths as persons under age 25 who are not accompanied by a parent or guardian and do not reside with their children. There were 36,907 unaccompanied homeless youth in January 2015, including 87 percent ages 18-24 and 13 percent under age 18. More than half of unaccompanied youth under age 18 were counted in unsheltered locations.

A quarter of all unaccompanied youth, 8,964, live in five major US cities: Los Angeles, Las Vegas, New York, San Francisco and San Jose, California.

HUD added a new category for 2015—parenting youth—defined as an individual under age 25 who is the parent or legal guardian of one or more children who sleep in the same place with him/her. There were 9,901 parenting youth in January 2015.

Homeless unaccompanied youth and parenting youth are those hardest hit by unemployment, low wages and student loan debt. This segment of the population, with or without children, is the most likely to live with relatives or friends and go uncounted by HUD and other surveys.

2015 estimates of homeless people by state SOURCE: US Department of Housing and Urban Development

2015 estimates of homeless people by state SOURCE: US Department of Housing and Urban Development

More than one in ten homeless adults are veterans. There were 47,725 homeless veterans on a single night in January 2015, or 11 percent of the 436,921 homeless adults. Veterans from the wars in Iraq and Afghanistan, Vietnam, Korea and the countless US imperialist exploits are included in this total.

Returning veterans suffering from post-traumatic stress disorder, brain injuries, substance abuse and other maladies struggle to find housing. Twenty-four percent of homeless veterans (11,311) live in California. Three other states had at least 2,000 homeless veterans: Florida (3,926), New York (2,399), and Texas (2,393).

In January 2015, 83,170 individuals were chronically homeless in the US. Two-thirds of these individuals, or 54,815 people, were staying in unsheltered locations, more than twice the national rate for all homeless people.

The number of unsheltered people with chronic patterns of homelessness increased by 4 percent over the past year, the first such rise since 2011. The number of unsheltered chronically homeless rose by 4,409 in Los Angeles alone.

Despite the massive increase in homelessness since the beginning of the financial crisis, funding for public housing has been repeatedly slashed in the post-2009 period. A report by the San Francisco-based Western Regional Advocacy Project noted that “HUD funding for new public housing units...has been zero since 1996,” while “Capital available to perform maintenance in 2012 [was] $1,875 billion,” representing a fall of $625 million over three years.

Mass homelessness is only the most acute manifestation of America’s housing crisis. According to a study published by Harvard University’s Joint Center For Housing Studies in June, the homeownership rate for 35-44 year-olds, which has been plunging for decades, has hit the lowest levels since the 1960s. Only slightly more than one-third of households headed by those aged 25-35 own their own homes.

The persistence of mass homelessness in the United States, despite six years of “economic recovery,” is an expression of the persistence of mass unemployment, falling wages, the slashing of social services, and the increasingly unaffordable living costs in America’s major cities, including Los Angeles and New York, that are home to a disproportionate share of America’s billionaires.

According to a poll released earlier this month, half of New Yorkers are “either just getting by or finding it difficult to manage financially.” More than one in five said they did not have enough money to buy food over the past year, and 17 percent said that they “have had times over the last year when they lacked the money to provide adequate shelter for their family.”

In the New York borough of Manhattan, median rent prices have grown by 9.5 percent over the past year. To afford a typical Manhattan apartment, one would have to pay over $40,000 a year in rent alone, 30 percent higher than the median wage in the United States. Not surprisingly, one recent study found that it is impossible for any worker making the minimum wage of $8.75 per hour to afford an apartment in any part of New York City—defined as spending no more than 30 percent of monthly income on rent.

The response of the “progressive” administration of Democratic Mayor Bill de Blasio to the deepening housing crisis in New York has been to further privatize public housing and drive up costs for low-income residents. De Blasio’s public housing plan, dubbed NextGen NYCHA, would jack up housing fees, such as parking, by up to several thousand dollars a year for low-income residents, while turning over more than 10,000 apartments and 11 acres of prime real estate to private developers.