Margot Miller

Around 1,500 people passed daily through the doors of Manchester City Art Gallery in the last few months to visit its powerful Sensory War 1914-2014 exhibition.

Held to mark the centenary of World War I, the gallery assembled both contemporary and historical art, adding to its already substantial collection of WWI art exhibits from the following countries: Germany, France, Italy, the Netherlands, the US, Canada, Japan, Vietnam, Algeria, Ireland, Iran, Israel and Palestine. The exhibition is part of the WWI programme coordinated by the Imperial War Museum, London, in galleries and museums across the country. It was presented in partnership with the city’s Whitworth Art Gallery and the Centre for the Cultural History of War at the University of Manchester.

Visitors were able to view the works of artists as divergent as British artists CRW Nevinson and Paul Nash and German artists Otto Dix and Heinrich Hoerle, both of whose works were banned by the Nazis as decadent. Six heart-rending woodcuts by Kathe Kollwitz are on display beside the fragile depictions from Japan by the Hibakusha (the survivors of the Hiroshima and Nagasaki atomic bombs). The latter have never previously been seen in the UK.

The exhibits were organised non-chronologically, in themes that relate to the sensory impact of war on the artist—hence the somewhat puzzling title of the exhibition. For example, the themes were titled Pain and Succour, Rupture and Rehabilitation, and Shocking the Senses. This is a weakness in the exhibition, because it detracts from a historical understanding of the economic and political conditions that produced two world wars separated by a mere 21 years, and the succession of regional wars in Vietnam, El Salvador, Yugoslavia, Africa and the Middle East.

The viewer is invited to regard war-torn scenes ripped from their historical context, from the standpoint of the individual and how it makes him or her feel, with the reality ultimately too horrible to comprehend. The words “imperialism” and “capitalism” are absent from the captions accompanying the artworks. Despite the significant gap, the exhibition is memorable and moving.

In the first section of the exhibition, the text explains the global nature of WWI, with 4 million soldiers enlisted from the colonies. The war was fought, not just in Europe, but wherever the imperialist powers had colonies in the Middle East and Africa. Ten million soldiers and 7 million civilians died.

In another section, the text emphasises the scale of the slaughter in World War II, which amounted to the death of 2.5 percent of the world’s population. A total of 24 million military personal and 55 million civilians died from the war, disease and famine, including 6 million Jews killed in the Holocaust. The exhibits are testimony to this devastation.

In Futurist style, official British war artist CWR Nevinson engraved Returning to the Trenches (1916), a small print showing a column of French soldiers returning to the front. Expressing the dehumanising effect of war in which men are just cogs in the war machine, clamouring billie cans, rifles and legs become a blur as the men march in lock-step back to battle.

CRW Nevinson: The Harvest of Battle (1918) (Art.IWM ART 1921)

CRW Nevinson: The Harvest of Battle (1918) (Art.IWM ART 1921)

By 1919, Nevinson had adopted a more realistic style to paint The Harvest of Battle. This is a painting of epic proportions in colours of mud brown and khaki, reminiscent of the dreaded mustard gas employed by both sides. Nevinson had joined the Friends Ambulance Unit and later worked for the British Red Cross at Dunkirk. He travelled to Ypres, Belgium, the site of the Christmas Truce between German and British soldiers in 1914, and was there at the beginning of the battle known as Passchendaele, one of the most intense and sustained battles on the Western Front. The barren landscape is dark, dismal and muddied, covered with stagnant pools under menacing skies. Weary stretcher-bearers tramp through the mud carrying the wounded. There is a corpse in the foreground, its mouth agape as if screaming, one arm raised in rigor mortis.

Writing to his wife from Ypres in 1917, British surrealist painter and war artist Paul Nash commented, “I am no longer an artist interested and curious, I am a messenger who will bring back word from the men who are fighting to those who want the war to go on for ever. Feeble, inarticulate, will be my message, but it will have a bitter truth, and may it burn their lousy souls.”

Paul Nash: The Landscape: Hill 60 (exh.1918 Pen and black ink, watercolour and coloured chalks on grey paper: Manchester City Galleries

Paul Nash: The Landscape: Hill 60 (exh.1918 Pen and black ink, watercolour and coloured chalks on grey paper: Manchester City Galleries

No life exists in fields of mud and shell holes. The sun fails in the grey, mud-coloured sky. A ruddy pool in the centre of the picture suggests death.

In another Nash painting, Wounded, Passchendaele, he departs from his usual depiction of war-ravaged landscapes without figures. The colours evoke the horrors of gangrene and mustard gas.

The large painting L’Enfer (Hell) (1921) by French artist George Leroux depicts the slaughter at Verdun in northeast France, where the French army lost a half-million men fighting the German army in 1916. One peers as if through fire and smoke and finally discerns the dead, who have become the colour of mud, in the mud.

Particularly emotive are six black-and-white woodcuts in a series entitled The War, by German artist Kathe Kollwitz, which evokes the grief and anguish of civilians in WWI. A testimonial to her son Peter who fell in the war, this series was first exhibited in 1924 at the newly founded International Anti-war Museum in Berlin. Kollwitz was already established as an artist who portrayed the poverty of the working class and peasantry in Germany. In The War: The Parents, the grieving parents are “entwined in mutual loss.”

Also exhibited are works by two other significant German artists, Otto Dix and Heinrich Hoerle. There are four black-and-white etchings from Der Krieg (The War) series by Otto Dix. These took inspiration from Goya’s The Disasters of War, which recorded the horrors of the Napoleonic invasion of Spain and the Spanish Wars of Independence in 1808-1814. In Seen on the Escarpment at Cléry-sur-Somme, painted in 1924, a soldier slumps, dead so long that a bird has made a nest in his gaping skull. His comrade with his lower jaw blown off appears to be laughing. In the picture The Mad Woman of Sainte-Marie-a-Py, a mother driven mad by grief amid the ruins of her house bares her breast as if to feed her dead baby.

Constructivist artist Heinrich Hoerle, who was involved in the Dada movement, which believed art should serve the cause of revolution, createdThe Cripple Portfolio in 1919. This series of 12 lithographs were first published in Cologne, inspired by the 2.7 million disabled war veterans, of whom 67,000 were amputees. Hoerle explored the psychological repercussions of the trauma the veterans suffered in life and even in their dreams. In Das Ehepaar (The Married Couple), painted in 1920, a couple embrace. Their furrowed foreheads are pressed together; she is clutching his prosthetic arm that ends in a hook.

Among the other notable works dealing with WWI are nine charcoal drawings by the lesser-known Italian artist Pietro Morando. A volunteer in the Italian Elite troops, he drew on anything he could find. His work has a startling immediacy, such as 1916’s A Remnant of the Last Action, which shows a soldier leaning in death on barbed wire. The artist was captured in 1918 and imprisoned in Nagymegyer, Hungary, where thousands of Italian civilians were interned and died. Morando sketched the torture, starvation, cholera and executions in the prison camp.

Two paintings bear witness to the Holocaust by artists commissioned to record the liberation of Bergen-Belsen.

In Belsen camp: The Compound for Women, painted by Leslie Cole in 1945, the nightmare that greeted the liberators is portrayed—10,000 unburied corpses, emaciated inmates in blue-striped pyjamas wandering forlorn.

In Human Laundry (1945), Doris Zinkeisen shows barely alive female survivors lined up in beds being washed and deloused in the section of the camp known as the Human Laundry. Their skeletal frames contrast pitifully with the rounded figures of the orderlies administering to them.

Introducing the Haunted Memories of the Hibakusha, the exhibition explains that at 08:15 on August 6, 1945 (when the Japanese high command were negotiating surrender, although this is not mentioned), a US bomber dropped an atomic bomb nicknamed Little Boy on the city of Hiroshima. Between 70,000 and 80,000 died from the initial blast and many more died later from their injuries and radiation sickness. On August 9, a second, even more powerful bomb was dropped on Nagasaki.

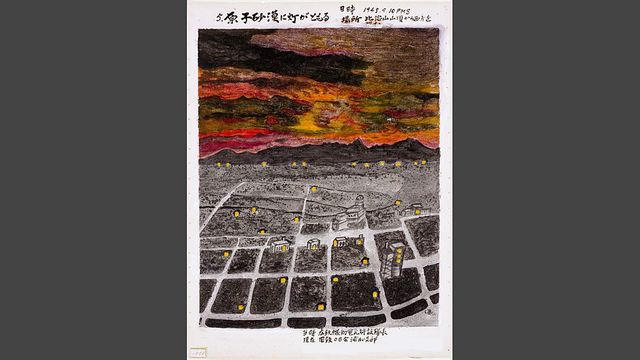

Gisaku Tanaka (age 72 at the time of drawing) Lights blinking on in the atomic desert (1973-4 Watercolour © Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, Japan)

Gisaku Tanaka (age 72 at the time of drawing) Lights blinking on in the atomic desert (1973-4 Watercolour © Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, Japan)

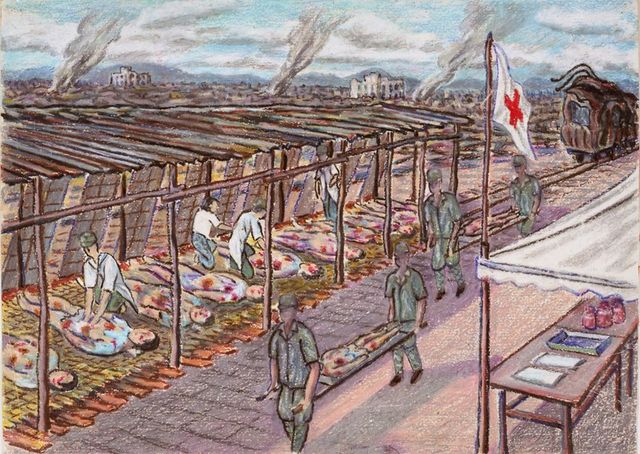

In 1974, a 77-year-old man named Iwachi Kobayashi gave a local TV station a drawing of the scene around the Yorozuya Bridge at about 4 p.m. on August 6, 1945. Inspired by this image, the TV station made an appeal to survivors to submit their memories of the atomic bombing. The response was overwhelming. Shown in this exhibition are 12 delicately constructed pictures portraying the horrific aftermath. Lights Blinking, by Gisaku Tanaka, was the artist’s view from Hijiyama Hill after the blast. The Red Cross hospital was painted by Fumiko Yamaoka, aged 47, in 1973-1974, when he committed his memories to watercolour.

Fumiko Yamaoka (age 47 at the time of drawing) Red Cross Hospital (1973-4 Watercolour © Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, Japan)

Fumiko Yamaoka (age 47 at the time of drawing) Red Cross Hospital (1973-4 Watercolour © Hiroshima Peace Memorial Museum, Japan)

These pictures deserve a wide circulation, a reminder of the unspeakable horrors of nuclear war at a time when US imperialism seriously contemplates engaging in a new war against China and Russia and is fomenting war on many fronts.

More-contemporary works include three anti-war pieces by Nancy Spero, one of which shows a fleeing woman cradling her child, in the context of the death squads and the “disappeared” of El Salvador in 1986.

The image of a black, hooded figure in Abu Ghraib is an indictment of the torture carried out by the US army and CIA in the Iraq war that began in 2003. Created in 2004 by Richard Serra, there exists a larger print with the words STOP BUSH.

Problematic is the juxtaposition in the Art Gallery of Sleeping Children (2012), by Sam Saimee, with the official UK war artist for the Iraq war John Keane’sEcstasy of Fumbling (Portrait of the Artist in a Gas Alert) (1991). In just a few hours on March 16, 1988, 5,000 Kurdish civilians were killed by mustard gas, and the nerve agents sarin, tabun and vx, in an attack ordered by then-Iraqi president Saddam Hussein. The dead children lie as if sleeping. This horrific slaughter of civilians took place during the Iran-Iraq war, when the Western powers supported and armed the Iraqi suppression of the Kurdish uprising in the north, which was backed by Iran.

Without explaining this, or the causes of the first Iraq war, placing this painting next to embedded artist John Keane’s work lends justification to the US “Desert Storm” war against Iraq in 1990-1991. The UN investigation into Iraq’s supposed stockpile of weapons of mass destruction, used to justify the invasion of Iraq in 2003, concluded that by 1991 Iraq had destroyed its chemical and biological weapons and had no WMDs.

Another controversial painting is a large 1994 canvass by Peter Howson called Croatian and Muslim. It portrays the rape of a Muslim woman during the Bosnian war. The Imperial War Museum, which commissioned the work, refused to show it because Keane had learned of the incident from the victim’s accounts—i.e., he wasn’t an eye witness—and it is today owned by the singer David Bowie. The artist came back from Yugoslavia traumatised.

There were atrocities on all sides in the Bosnian civil war between the rival Croat, Bosnian Muslim and Serbian cliques, following the imperialist-backed dissolution of Yugoslavia. The US cynically employed the pretext of humanitarian defence of the Bosnian Muslims to intervene militarily.

The most moving and accessible art works all tell a profound truth—that it isnot a “sweet and fitting thing to die for one’s country.” In the words of murdered German revolutionary Karl Liebknecht, who was so lovingly portrayed by Kathe Kollwitz, “Ally yourselves to the international class struggle against the conspiracies of secret diplomacy, against imperialism, against war, for peace within the socialist spirit.” With a call to disarm the war-mongering capitalist class, he said, “The main enemy is at home.”

No comments:

Post a Comment