Margot Miller

Thirteen months after the Grenfell Tower fire in London that killed 72 people, tens of thousands throughout the UK are still residing in tower blocks covered in flammable cladding.

Despite government promises, 297 tower blocks remain wrapped in cladding with an aluminium composite material (ACM). ACM, and the inept manner in which it was attached to the building, was the main factor contributing to the rapacious fire spread at Grenfell Tower, where a small fire breached one flat and within half an hour engulfed the whole building.

The role of the cladding in the fire speed and spread was confirmed at the government inquiry begun September 14 last year. The cladding was chosen because it was cheaper than a non-combustible

By contrast, another fire, on July 3, on floor 16 of Whitstable House Tower block in North Kensington—adjacent to the charred remains of Grenfell—was easily contained and doused by firefighters. In this instance, the block was not encased in ACM. Whitstable, despite many other problems, had its original fireproof concrete exterior.

In May this year, the Conservative government pledged £400 million to remove ACM from council and housing association blocks. The money is being taken from the Affordable Homes Programme—itself an inadequate government response to the burgeoning UK housing crisis.

Yet only seven tower blocks have had remedial work done. According to Inside Housin g, in “August, then communities secretary, Sajid Javid wrote to the sector to say it [the government] expected landlords to meet the cost. Since then it has resolutely refused to budge on providing a penny towards the work.”

Similarly, in the private sector, remediation is barely moving.

The 132 private blocks identified as having ACM are a gross underestimation, said Inside Housing. Many buildings have not been tested. In 74 percent of cases, the government has not been informed of remediation plans. Work has begun on only 23 with only 4 decladded.

Private sector leaseholders are as concerned as public sector tenants. In many cases, their landlords—the freeholders who own the land where the blocks stand (who may or may not be the original developer)—are demanding flat owners or insurers pay remediation costs.

The then-Housing Minister Dominic Raab said “private sector companies should not pass costs onto leaseholders.” At a Westminster meeting, Head of Building Safety Programme Neil O’Connor said the government informed developers by letter that leaseholders should not pay.

Even when developers concur, this does not resolve the legal tangle of who foots the bill.

Developer Galliard Homes, builder of 1,000 ACM-covered homes in Capital Quay in Greenwich, London, has lodged a claim in the high court against insurer NHBC—hoping the court will rule the insurer pays the £25-£40 million remediation bill.

To date, only four developers or insurers have agreed to finance remediation of tower blocks they neglected to make safe in the first place.

Developer Barratt eventually agreed to put right the Cityscape block in Croyden, at a cost of £2 million, despite a tribunal ruling that residents should pay. Last November, Legal and General agreed to cover the cost of recladding a 330-home development in Hounslow. Taylor Wimpey has agreed to pay for safety work at a development in Glasgow Harbour. Developer Mace confirmed it would finance the recladding on its £225 million Greenwich Square project in London.

A property tribunal recently decided in favour of Property giant Pemberstone against the residents of private blocks Vallea Court and Cypress Place, in the Green Quarter of Manchester.

The 345 flats were built in 2013 by international conglomerate Lendlease. Lendlease sold the freehold on to Pemberstone, which receives leasehold payments from the flat owners.

The tribunal ordered the residents to pay £3 million for recladding, fire patrols and Pemberstone’s legal fees, through a hike in their annual service charge.

Many residents bought their homes under the government’s help-to-buy scheme. They represented themselves at the tribunal after crowd-funding raised £11,000 for legal advice.

One resident expressed his utter frustration to the BBC’s current affairs programme File on 4. “I purchased my flat from major developer Lendlease with a 10-year warranty,” he said. “Any responsible company would have been rushing to get the cladding off, but they’re all passing the buck, saying it’s not us.”

Residents were also enraged to learn that Manchester’s Labour-led council is considering awarding Lendlease a £190 million contract to refurbish the city’s historic town hall.

Greater Manchester Labour Mayor Andy Burnham expressed his party’s indifference to the dangers facing occupants of high-rise blocks wrapped in ACM. All he offered residents of Vallea Court and Cypress Place were vague assurances stating that the “High Rise Taskforce, which I established immediately following the Grenfell tragedy, [means] Greater Manchester Fire and Rescue Service now works…to ensure the right fire safety measures are in place until the cladding can be replaced.”

Spruce Court with cladding removed on just the first three floors

Spruce Court with cladding removed on just the first three floors

Residents whose lives are at risk are growing angry. The WSWS spoke to council tenants in Salford, north west England. In Salford, there are 29 blocks covered with ACM cladding—the highest concentration in the UK.

Labour-run Salford City Council, led by Mayor Paul Dennett—a supporter of Labour’s nominally left leader Jeremy Corbyn—runs nine blocks via management company Pendleton Together. The other 20 blocks with flammable cladding used to be council-run but are now owned by housing associations Salix Homes and City West Housing Trust.

Last August, the council announced it was borrowing £25 million to declad its nine blocks.

To date, most of the council flats are like Spruce Court—with cladding removed from the first three floors but no remedial work done.

Eileen, a 55-year-old parent, told WSWS reporters her son lives on floor 16 of Spruce Court. “They’ve gone for the cheapest [cladding]. It all boils down to money. Somebody came round taking photos, just to make us think they’re doing something.”

Alan

Alan

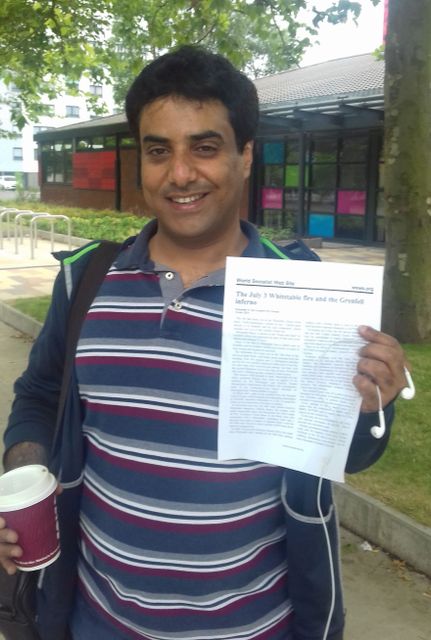

Student Alanzi from Kuwait said, “In my country we have 50, 60 floors. We can control any fire. We have building technology to make flats safe. I’m living floor 18 [in Salford], it’s very dangerous, there’s no safety.”

Marlene, from Malus Court, complained about the lack of information from the council or freeholders. “They’re not telling us anything,” she said.

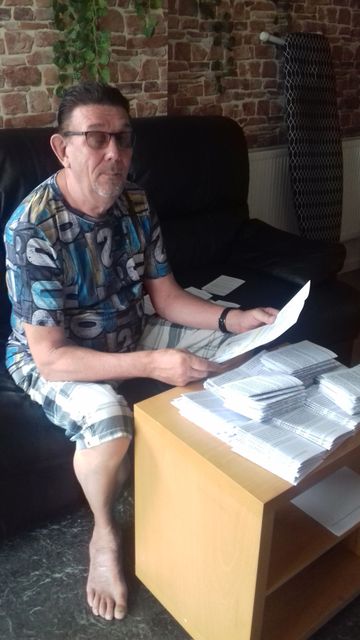

Jon Smith, who is 72, has been an active campaigner for the removal of flammable cladding since the Grenfell fire. WSWS reporters spoke with him at his flat on the sixth floor of Thorn Court.

Jon Smith

Jon Smith

Jon was in the middle of folding leaflets to organise a fight back that said “it’s now time to stand united…all nine blocks [managed by Pendleton Together] that still have the cladding on.”

Jon explained that “within 30 minutes of putting a leaflet up in the foyer of Spruce Court, the housing officer removed it from the notice board. The council do not want us coming together. We’ve had enough.”

As to the council’s promises to remove the cladding over the next two years, Jon said, “Two years is rubbish,” pointing out the slow pace of the work. “How’s it going to take two years with nine blocks. It’s a disaster! I’m going to sit outside Brotherton House [Pendleton Together] with a petition. We want this [cladding] removed now, the windows replaced and the electrics checked.

“They’ve asked for a war and that’s what’s going to happen.”

No comments:

Post a Comment