Brian Dixon

Each year in the United States some 700 mothers die giving birth, while over 50,000 are severely injured. According to an investigation published by USA Today last Thursday titled “Deadly Deliveries,” the majority of these deaths and injuries could have been prevented if hospitals had followed best practices for delivering babies.

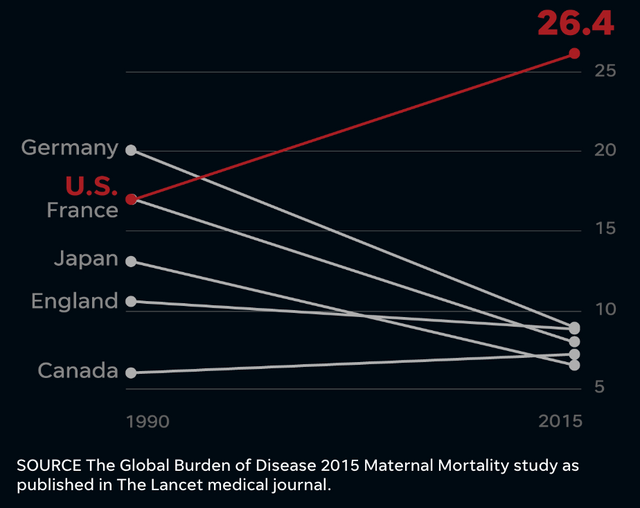

The Global Burden of Disease Study 2015, put together by researchers at the World Health Organization and published in 2016 in the medical journal The Lancet, reported that maternal deaths in most industrialized countries have either declined or remained flat since the 1990s, with countries in Western Europe falling below 10 maternal deaths per 100,000 births.

By contrast, the maternal death rate in the United States has nearly doubled, increasing from 16.9 deaths per 100,000 births in 1990 (for a total of 674 deaths) to 26.4 in 2015 (a total of 1,063 deaths). Based on this data, the USA Todayarticle concluded that the United States is the most dangerous country in the developed world for women to give birth.

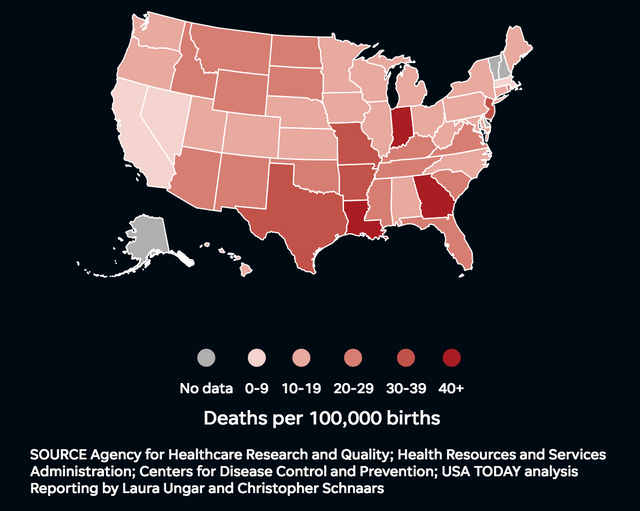

Maternal deaths US by state

Maternal deaths US by state

The investigation by USA Today helps shed light on why this is the case. It found that many US hospitals have failed to implement basic and inexpensive safety standards—such as weighing bloody pads to measure blood loss or administering medication in a timely fashion to treat spikes in blood pressure—that could prevent the majority of maternal deaths and injuries.

The maternal death rates varied by state. California, considered by leading medical societies to represent the gold standard of care, saw maternal deaths decline by half to 4 deaths per 100,000 births. On the other hand, Louisiana, Indiana and Georgia have the highest maternal death rates, exceeding 40 deaths per 100,000 births—similar to the rates found in Guam, Egypt and Tunisia. Louisiana’s maternal death rate of 58.1 deaths per 100,000 births is actually higher than the rate in Central Latin America (55.9).

The investigation was based on over 500,000 pages of internal hospital quality records from hospitals in the states of New York, Pennsylvania and the Carolinas, covering 150 women who suffered childbirth complications, along with interviews with mothers, family members and hospital administrators.

The newspaper found that US hospitals have been slow to adopt new safety guidelines that have been recommended by medical societies and other health organizations for nearly a decade.

There are no national regulations requiring hospitals to make data on childbirth complications public and hospitals are reluctant to release such data, making it difficult to identify facilities with major problems. For example, the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services does not require the reporting of any complications in childbirths covered by Medicaid, which pays for almost half of the 4 million births that take place in the US each year. The private hospital accreditation group the Joint Commission requires the reporting of cesarean section rates, but no other information.

“Our medicine is run by cowboys today, where everyone is riding the range doing whatever they’re wanting to do,” Dr. Steven Clark, a leading childbirth safety expert at Baylor College of Medicine, told USA Today.

The lack of national regulation means that hospitals can ignore safety recommendations, a problem common to hospitals of all sizes and all levels of technological sophistication. As a result, less than 15 percent of mothers suffering childbirth complications in the hospitals looked at by investigators received the recommended treatment.

Maternal deaths in US vs. Europe

Maternal deaths in US vs. Europe

The primary sources of complications arise from dangerously high spikes in blood pressure that can lead to strokes and excessive blood loss, which can result in organ failure.

Medical societies and other health-related organizations have developed guidelines for treating pregnant women and new mothers for high blood pressure, including additional monitoring and treating them with medication within one hour. The newspaper, however, found that many hospitals failed to follow these guidelines.

In the dozen or so medial facilities USA Today looked at in Pennsylvania, hospitals failed to follow treatment guidelines 33 to 51 percent of the time, while two hospitals in the Carolinas had failure rates of 78 percent and nearly 90 percent. At one of the largest birthing hospitals in North Carolina, the Women’s Hospital in Greensboro, between October 2015 and June 2016, 189 out of 219 mothers were not given timely treatment for high blood pressure, despite medical staff being aware that their work was being monitored. The newspaper estimates that 60 percent of the deaths from hypertension could have been prevented.

Other mothers experienced excessive bleeding, resulting in their blood pressure dropping to dangerously low levels and posing the threat of organ failure. This can be prevented by carefully measuring the quantity of blood loss by weighing blood-soaked pads and collecting and measuring blood using a calibrated pouch. When medical staff make only visual measurements, they often underestimate the level of blood loss, while doctors may mistake the excessive blood loss for normal post-partum bleeding.

According to a 2016 training webinar put on by the country’s main hospital trade association, the American Hospital Association, 93 percent of the women who bled to death could have been saved had staff paid attention to the level of blood loss.

Many of the women interviewed by the newspaper expressed the common complaint that doctors and nurses did not listen to their concerns and were often ill prepared. The mothers experienced excruciating pain and most were never provided with an explanation for what went wrong.

“Over and over,” the article notes, “these women said they wanted other mothers to know the importance of finding heath care providers who listen to their concerns, pay attention to warning signs and are trained to deal with complications.”

Of the 75 hospitals in 13 states contacted by USA Today, half refused to answer questions about their safety practices. Of those that did reply, over 40 percent admitted that they did not quantify blood loss after birth, while the majority had no system for tracking whether women with dangerously high blood pressure were treated in a timely fashion.

Unlike other developed countries, the US does not have a national health care system that could mandate the use of best practices, meaning it can take a decade or more before they are widely implemented, resulting in hundreds of unnecessary deaths and tens of thousands of unnecessary injuries, primarily afflicting working class women.

While the newspaper indicates some of the problems underlying the preventable deaths and injuries—including the lack of national regulations and inadequate training for medical staff—it ignores the primary problem of the profit motive in health care. For example, while the article is quick to place blame on medical staff, it ignores the long hours and unsafe patient-to-staff ratios imposed on nurses as hospitals attempt to keep down labor costs at the price of patient safety.

No comments:

Post a Comment