John Helmer

Moscow.

Works of art are only reliable investment assets if the trade in them is tested and transparent enough to prove they aren’t stolen goods, forgeries, or what is known in Russian as falshak (фальшак), a term originally applied to counterfeit coins.

Naturally, as the art trade generates higher and higher prices for individual works, the lure of expensive objects becomes irresistible for those with cash on the run. That is, if it can be laundered, er exchanged, through international auction houses like Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Bonhams – institutions less regulated, and apparently more reputable than banks. Just as these house names claim to be setting records for auction prices for their goods, the margin of profit to be gained from fraud and forgery attracts almost as many well-heeled crooks for sellers as for buyers.

The relatively short time in which Russian art has been traded in international markets has meant that the swiftly earned riches of the Russian oligarchs have been bidding up auction house prices for objects with dim histories, uneducated demand, and short or non-existent records of ownership. For a London auction house like Bonhams, the record-setting value of Russian art it has been able to find for sale has turned into an opportunity for exchanging the auction house itself for cash. If the privately-owned Bonhams, whose turnover is a tenth of the two bigger houses, were to trade at the price to earnings ratio (P/E) of Sotheby’s, it might fetch over £530 million. But prices like that don’t fetch if there is slightest suspicion of falshak.

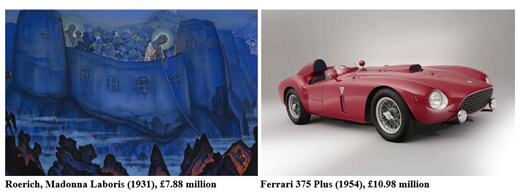

Bonhams has been selling itself, according to the Financial Times, for its success at taking a corner on two markets – vintage cars and Russian paintings. It has set the market record for “the most expensive Russian painting sold at auction: the ‘Madonna Laboris’, by Nikolai Konstantinovich Roerich, fetched £7.9m.” At the time – June 2013 – Bonhams

claimed [1] the Roerich work was “the most valuable Russian picture ever to be sold in a Russian art auction.” Last November, Christie’s beat the Bonhams record with the sale of Valentin Serov’s Portrait of Maria Zetlin for £9.2 million; for that story, and the Russian record table, click

here [2].

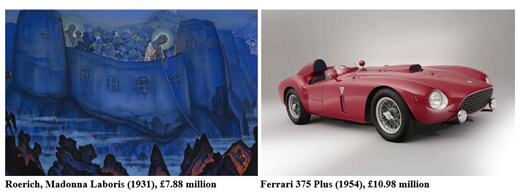

Bonhams’ cars have turned out to be pricier than its Russian paintings, and there’s the rub. One of the priciest, a Ferrari 375 Plus, turns out to be stolen goods. That’s according to at least five, maybe six claimants now in court in the US and in London. As for Russian painting,

Bonhams [1] was lucky to “rediscover” the Roerich Madonna; since then it has been unable to sell Russian paintings for anything like a record, either for lot or for batch.

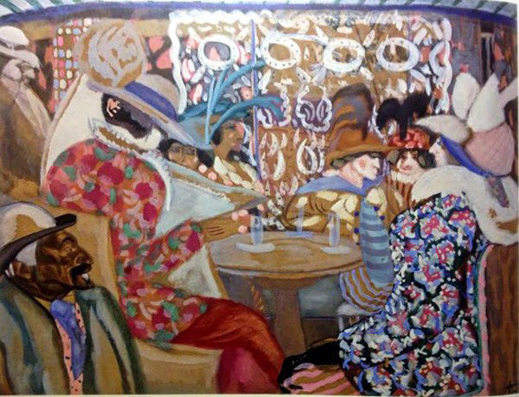

Worse, there is still controversy among Russian experts over an attempt Bonhams made in 2008 to sell a work by

Alexandra Exter [3], an artist of the Russian Avant-Garde of the 1920s. That painting (lead image), ‘Study for Venice’ of 1924, was withdrawn from sale in circumstances the experts and auctioneers aren’t willing to discuss on the record.

A Russian art expert, Yevgeny Zyablov (right), chairman of the board of

Art Consulting [4], concludes that “the reliability of Christie’s

and Sotheby’s is higher. More controversial things, or things without attribution or elaboration, you can meet at Bonhams.”

So what has become of the

Financial Times [5] attempt to promote the sale of Bonhams itself? According to the newspaper’s report of July 2014, “people close to the group said they were hoping to complete a sale by the autumn.” The newspaper claimed Poly Culture of China was one of four bidders – the others were Bain Capital, CVC Capital and Bridgepoint. CVC is a shareholder in Formula 1; neither it, nor Bain and Bridgepoint had taken an equity stake in a business like Bonhams; their names may have been planted. A few weeks after the Financial Times reported, Bain, CVC and Bridgepoint were

reported [6] to have dropped out, leaving Poly Culture, the only one of the four to operate within the fine arts, with a price offer for Bonhams reported to be “several hundred million pounds”.

Poly Culture [7] was listed on the Hong Kong Stock Exchange in March 2013, initially valued at

HK$33 per share [8]. It then jumped to $45, but steadily slipped over the past two years. Its current share price of HK$24 gives Poly Culture a market capitalization equivalent to £512 million. It is trading on a price-earnings ratio of 11.5. So based on Bonhams’ reported financials for 2013, the Chinese ratio should give Bonhams a valuation of about £300 million. If Bonhams were valued on Sotheby’s P/E of 20.5, it might be worth

£533 million [9].

The Poly group says it originated as a joint venture in the 1980s between the People’s Liberation Army and CITIC, a giant state-owned conglomerate, best known in China for its CITIC Bank. Poly Group’s current lines of business include military technology, real estate, and popular entertainment, as well as

art auctions [10]. The company hasn’t said a word about its reported interest in Bonhams; it refused this week to answer questions about its reported bid.

Bonhams [11] is jointly owned by two businessmen: Robert Brooks (below, left) and Evert Louwman (right), a Dutchman. Both were racing car drivers; both traders of new and used cars. Brooks was also an

auctioneer [12] for Christie’s, and the owner of the London premiseswhich Bonhams rents out.

By mid-September Poly Culture was

reported [13] in London to have dropped out of the Bonhams bidding – and there was noone left. A source claims Bonhams was asking for £350 million, whilst the source claims the Chinese were only willing to offer between £250 million and £275 million. Independently, Reuters reported bank sources as claiming they had put together a loan of about £200 million to back the bidding. By then, Bonhams had acknowledged an outright sale to a single investor was the only chance it had to generate an equity profit, all earlier attempts to find underwriters for a stock exchange listing having

failed [12].

Financial reports filed by Bonhams reveal that in 2013 it valued its assets at £112.9 million. Revenue was £127.1 million; earnings (Ebitda) £26 million; profit £15.7 million. These numbers were all up healthily over 2012.

Between the start of the bidding for Bonhams and the drop-outs, a group of claimants to a Ferrari Bonhams had sold went to the High Court. The lead claimant, Leslie Wexner (right), an American underwear merchant, demanded that Bonhams return of more than £12 million – that covered the purchase price of the car which Bonhams had auctioned on June 27, 2014, plus legal costs. This story hit the newspapers in November of 2014.

The disclosure of Bonhams’ financials for 2014 is running late compared to last year. Because of the litigation over the Ferrari, the provision for liability of just over £1 million in the 2013 financial report is likely to rise to the court claim figure, plus legal costs. At about £12 million that may be enough to push Bonhams into loss.

This isn’t the first legal fracas Bonhams has faced for mis-selling Ferraris. In May of 2013, Bonhams had auctioned a 1959 Ferrari, subtitled Ferrari 410 SuperAmerica Series III Coupe, for which a London antiques dealer Thierry Morin paid Bonhams £480,000, following a fiercely contested auction. Bonhams had claimed in sale advertising the car had done “a mere 16,626 km”. Court action followed when Morin discovered the car had almost certainly done more than 200,000 kms.

Had Bonhams been tampering with the odometer — was it lying to defraud? Morin went to the High Court in London for the contract to be

cancelled[14], and his payment, plus costs, returned. The High Court ruled against him, on the jurisdictional ground that it was a Bonhams subsidiary in Monaco which had done the deal, not the London parent. “M. Morin does not have a reasonably arguable case against B&B London that they owed him a duty of care, ” wrote the judge, Jonathan Hirst. but he rule that if Morin sued in Monaco against the Bonhams compay there, “[he] certainly has an arguable cause of action against B&B Monaco in Monesgaque law if he can establish a misrepresentation as I am satisfied he can.”

“If it is right,” Hirst decided against Bonhams, “that the Ferrari had actually done over 200,000 kms, it is a matter of real concern how an international auction house could have stated that it had done “a mere 16,626 kms” when (if Mr Grist’s evidence is accepted) a short road test would have revealed the true position….For this latter reason, I would also conclude that M Morin had a reasonable prospect of showing that B&B Monaco was in breach of any duty of care.”

This year’s Ferrari problem for Bonhams is the evidence that the car had been stolen in 1989 and that Bonhams knew there was an ongoing dispute among several claimants when it told Wexner otherwise. According to court papers available last week, Wexner’s lawyers argue, “Bonhams knew that if it honestly revealed the true position regarding the challenges to title to the car, no-one would even consider buying it. This is apparent on the face of Bonhams’ own evidence… Bonhams knew that to auction the car successfully it had to present it on the basis that the long-running dispute around it had been resolved and that there was no challenge to the sellers/consignors’ title. When it realised that that would not be possible, it could have done the honest thing and pulled the car. But it knew that the financial consequences of doing so would be disastrous. So, instead, Bonhams pushed ahead with the auction and told the world and the Buyers what it knew was not true: that, in short, a purchaser would take the car free of any known risk of challenge to title.”

At this point there are six claimants to the car, including Wexner. No trial is likely before April of 2016. For the time being, according to the court documents, Bonhams is refusing to put in writing what it intended to mean by the pre-auction representations it issued on the Ferrari. One of the claimant buyers has asked the court to order a forensic inspection of the chassis, brake drums, and take metal shavings to determine whether the metal is as old as Bonhams claims the car to be.

In court last week Justice Julian Flaux said: “This case requires momentum and robust case management. The idea that it should maunder on does not seem appropriate.” Evidently frustrated by the competing claims, he demanded that by the date of the next hearing, May 5, Wexner and the others, including Bonhams, should agree on a list of issues to be decided. The judge also suggested that mediation might be a better option, because the longer the litigation goes on, the faster the asset will depreciate. The reputational and financial risks to Bonhams also grow as the case drags on.

Bonhams has issued a press statement: “we are satisfied that any claim is wholly without merit and will be strongly contested.” In court papers Bonhams claims that before the sale to Wexner it had brought the parties together; that the ownership dispute had been resolved; that “all relevant litigation had been settled”; and that Bonhams knew of “no reason why . . . the buyer should not be able to register title in . . . the USA.” Wexner and the other claimants are saying Bonhams is lying. According to its defence, “the idea that Bonhams would have participated in the fraudulent activity alleged against it is absurd”.

The impeachment of Bonhams’ credibility and the failure of its sale to investors cast a shadow over the Russian art market, not only because the mystery discovery of Roerich’s Madonna and the record price it fetched aren’t likely to be repeated. Misrepresentation, fraud and forgery aren’t unique to Russian art, according to Simon Hewitt, international editor of

Russian Art + Culture [15]. “Russian Art has attracted forgers in specific, lucrative areas, particularly the late 19th century (Shishkin, Aivazovsky) and the early 20th century Avant-Garde. In my opinion, there is as much forgery of Flemish old masters as there is of late 19th century Russian paintings.”

“The Avant-Garde is a case apart,” Hewitt adds, “because the KGB set up something of a forging industry in the field as a way of accessing gullible foreign cash. They had access to materials dating from the 1920s which enabled many of their fakes to pass chemical testing with flying colours. When researching a piece for ART + AUCTION a few years ago I was informed by one high-profile source that the post-KGB forging industry continues, with practitioners based in ships off the Israeli coast (as well as Germany).”

It has been much easier also to get away with forgery in Russian art, at least in the 1990s. “Spurious authenticity certificates could be had from chronically underpaid and easily corruptible Russian museum officials for a pittance until quite recently, but this is less and less the case.”

Pyot Aven (below, right) of the Alfa Bank group, and one of the largest collectors of Russian art, has called in experts to authenticate the paintings in his own collection. In 2011, he called a press conference to report that a criminal gang based in France and Switzerland was flooding the market with fake watercolours by Natalia Gonacharova (left). “[She] never did watercolour versions of her oil paintings”,

Aven said [16].

Aven’s collection is reported to hold 400 paintings, with a value estimated

last November [17] by Forbes at $500 million. They are works of the late 19th century and early 20th century.

Vyacheslav Kantor [18], owner of the Acron fertiliser group, has an equal sized collection; he specializes in Russian Jewish artists of the early 20th century, whose collection value is also estimated by Forbes at $500 million.

In Forbes these are advertisements for asset value, resale profit, collateral credit. The loopholes in the Forbes calculation are authenticity and dealer fraud. In November the publication claimed Dmitry Rybolovlev’s (below, left) collection was worth $700 million. This month fraud indictments in Monaco, France and Switzerland, initiated by Rybolovlev against his art dealer Yves Bouvier (right), reveal that the paintings were over-valued and Rybolovlev over-charged.

Just how little an oligarch’s collection may turn out to be was revealed when liquidators of

Boris Berezovsky’s [19]estate discovered he had laundered his money too quickly, and carelessly, into works that turn out, on examination now, to be forgeries. Works that Forbes would put up to £50 million turn out to be a fraction.

For litigation by another fertilizer specialist, Andrei Melnichenko of Eurochem, to prove he had been defrauded by a New York art dealer, click

here [20]; Melnichenko didn’t win. For Victor Vekselberg, who did win in a London court over Christie’s in the case of a fake Kustodiev painting, read

this [21].

Right now, a St. Petersburg court is hearing criminal charges of conspiracy to commit fraud by Elena Basner in the certification, then sale, of the 1913 painting, “In the Restaurant” attributed to Boris Grigoriev (below). Bringing the charges is the collector,

Andrei Vasiliev [22]. The Russian press coverage of all sides in the affair, which

Basner [23] has called a frame-up, is voluminous.

The Russian expertise on which museums rely are the Art Research and Restoration Centre named after Academician Igor Grabar (GRC) and the State Tretyakov Gallery. They say they do not make public comments.

Yekaterina Kartseva, co-owner and founder of

Privatecollections.ru [24], says that Russian art forgery is exposed regularly, particularly of 20th century and contemporary works. “Less high-profile cases occur quite regularly; many of my friends who bought a painting at auction cannot obtain confirmation of authenticity at the Tretyakov Gallery. Major Russian auction houses are trying to keep track of their reputation, but many are bombarded with lawsuits. Most problems arise with online auctions, since there it is more difficult to keep track. Major Western auctions rarely bring cases to court. At Sotheby’s, as far as I remember, the buyer has three months in which to return the work. If the work is brought to us, we will examine it, make contact with the experts at Sotheby’s, and if the experts do not agree, there is three months for the buyer to make a decision.”

Kartseva suspects there may be forgeries in well-known collections, such as the collection of cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, which was bought by Alisher Usmanov at Sotheby’s in 2007. Usmanov (right) paid £25 million ahead of the auction, and then presented the works to the state. Paintings by Grigoriev and Roerich led the Sotheby’s estimates, which were roughly five times the prices

Rostropovich had paid [25].

Suspicion doesn’t always result in an unambiguous certificate, Karsteva concedes. “Authentication may end up with a statement like, ‘the work does not conflict with the brush of a certain author’…the opinion of some experts do not necessarily reflect the opinion of others. The art market is certainly more prone to fraud, which is stimulated by the very high price of some of the works, when it isn’t clear whether the collector’s motive is to buy the painting itself or to demonstrate for all to see the cash equivalent. If you bought an image, is it important for you for the object to be the original or a copy?”

Zyablov of Art Consulting explains that as the economic stringencies being felt by buyers get worse, demand is restricting price, and the circulation of forgery is contracting. “Our company was created in order to protect investors — we have a very tough procedure. For this reason the British market takes our expertise for insurance of private collections. During the growth of the market, investors (buyers) had high hopes for this market. They bought a lot of things that were attributed by some experts without evidence, and sometimes without provenance. Now all these things are out of the market. You can appreciate too that when the market itself has fallen in volume, the number who want to make fakes and sell them is greatly reduced. Market expertise in Russia has also developed strongly to stop counterfeiting.”

A Moscow art market source explains that just as the incentive to forge is bound to grow as art prices grow, so does the expertise to detect it. When prices were in the low thousands of pounds, he said, the gallery or auction house commission would be roughly equal to the cost of high-quality chemical and other testing to authenticate a work. Russian buyers started out naïve, and if prices were low, they didn’t need to be careful. Once prices reached the millions of pounds,though, the demand for expertise intensified, and the cost was affordable for the auction houses.

About the Rostropovich collection, Zyablov says: “of course, things can turn out to be fake, and this might be found in many different collections. For example, Pyotr Aven commissioned us to examine and evaluate his collection for insurance purposes. From a few hundred things we found two things which were wrongly attributed. Pyotr Olegovich was grateful to us, and talked about it at a press conference. So, such cases happen.”

Auction houses like Christie’s, Sotheby’s, and Bonhams maintain their own experts, Zyablov adds. “Experts with the same specialization compete for credibility. Those who stand on the side of the market, and are more lenient in their assessments, get promoted by the market. In this way, there’s better business for experts who are less tough. This is a paradox. The trend of expertise to protect the buyer goes against the trend of the market, which favours higher priced sales.”

A Russian art expert, Yevgeny Zyablov (right), chairman of the board of

A Russian art expert, Yevgeny Zyablov (right), chairman of the board of

Between the start of the bidding for Bonhams and the drop-outs, a group of claimants to a Ferrari Bonhams had sold went to the High Court. The lead claimant, Leslie Wexner (right), an American underwear merchant, demanded that Bonhams return of more than £12 million – that covered the purchase price of the car which Bonhams had auctioned on June 27, 2014, plus legal costs. This story hit the newspapers in November of 2014.

Between the start of the bidding for Bonhams and the drop-outs, a group of claimants to a Ferrari Bonhams had sold went to the High Court. The lead claimant, Leslie Wexner (right), an American underwear merchant, demanded that Bonhams return of more than £12 million – that covered the purchase price of the car which Bonhams had auctioned on June 27, 2014, plus legal costs. This story hit the newspapers in November of 2014. Bonhams has issued a press statement: “we are satisfied that any claim is wholly without merit and will be strongly contested.” In court papers Bonhams claims that before the sale to Wexner it had brought the parties together; that the ownership dispute had been resolved; that “all relevant litigation had been settled”; and that Bonhams knew of “no reason why . . . the buyer should not be able to register title in . . . the USA.” Wexner and the other claimants are saying Bonhams is lying. According to its defence, “the idea that Bonhams would have participated in the fraudulent activity alleged against it is absurd”.

Bonhams has issued a press statement: “we are satisfied that any claim is wholly without merit and will be strongly contested.” In court papers Bonhams claims that before the sale to Wexner it had brought the parties together; that the ownership dispute had been resolved; that “all relevant litigation had been settled”; and that Bonhams knew of “no reason why . . . the buyer should not be able to register title in . . . the USA.” Wexner and the other claimants are saying Bonhams is lying. According to its defence, “the idea that Bonhams would have participated in the fraudulent activity alleged against it is absurd”.

Kartseva suspects there may be forgeries in well-known collections, such as the collection of cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, which was bought by Alisher Usmanov at Sotheby’s in 2007. Usmanov (right) paid £25 million ahead of the auction, and then presented the works to the state. Paintings by Grigoriev and Roerich led the Sotheby’s estimates, which were roughly five times the prices

Kartseva suspects there may be forgeries in well-known collections, such as the collection of cellist Mstislav Rostropovich, which was bought by Alisher Usmanov at Sotheby’s in 2007. Usmanov (right) paid £25 million ahead of the auction, and then presented the works to the state. Paintings by Grigoriev and Roerich led the Sotheby’s estimates, which were roughly five times the prices