Patrick Martin

Three more multi-millionaires announced their candidacy for the Republican presidential nomination Monday and Tuesday, bringing the total number of declared candidates to six. As many as a dozen others are openly campaigning, raising money, or participating in forums, without yet formally declaring.

Two weeks ago a forum in New Hampshire, the first primary state, drew a staggering 19 active or potential candidates, who addressed hundreds of Republican Party activists in the course of two days. These included four US senators, four governors, six former governors, one former senator, and a US congressman, as well as three who had never held political office.

The multiplication of Republican candidates is the byproduct of several factors, including the lack of any credible frontrunner—which reflects the general unpopularity of the party’s ultra-right policies—and the factional divisions among ultra-right Tea Party elements, Christian fundamentalists, corporate executives, and the direct representatives of the military-intelligence apparatus.

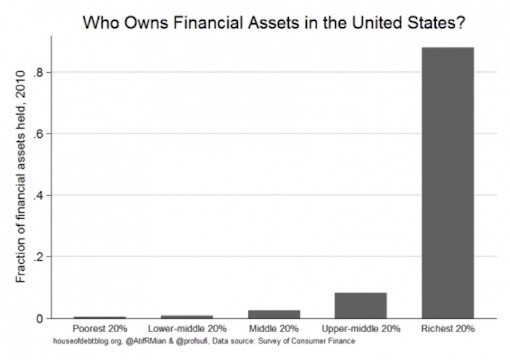

But one factor is of overriding importance: the flood of money into the two big business parties, particularly in the wake of the 2010 Supreme Court decision in the Citizens United case, which effectively scrapped all limitations on campaign contributions.

As a result, virtually any candidate, no matter how obscure or erratic, can sustain a presidential bid—at least during the year before actual voting begins—providing he or she can find a billionaire backer willing to put up the money. Many of the Republican presidential hopefuls are participating in the hope that a well-received speech or television appearance will allow them to hit that jackpot.

On the Democratic side, the influx of big money seems to have produced the opposite result. The presumptive nominee, former secretary of state Hillary Clinton, has the active or passive support of all the available politically active billionaires, who are less numerous on the Democratic side than on the Republican. As a result, she faces only one declared opponent, Vermont Senator Bernie Sanders, with few significant challengers waiting in the wings.

On the Republican side, it requires a $50 million campaign war chest for 2015 alone—the year before the election—to be taken seriously as a candidate. The influence of big money accounts directly for the early announcements by three US senators, Ted Cruz, Rand Paul and Marco Rubio, because as federal elected officials they can only raise money directly as declared candidates for the presidency. Governors like Scott Walker of Wisconsin and Chris Christie of New Jersey, as well as ex-governors like Jeb Bush of Florida, have no such restrictions, and can raise vast sums of money even before the formal declaration.

None of the three candidates who joined the Republican presidential race this week is likely to win the nomination, but the combined effect of their entry is to push the campaign even further to the right. Each of the three candidates demonstrates, in different ways, that holding false, retrograde, and virtually demented views is no barrier to being treated as a serious presidential candidate—provided you declare your unflagging loyalty to capitalism, religion and the US military.

Retired neurosurgeon Ben Carson declared his candidacy Monday morning at a rally at the Music Hall in downtown Detroit, his birthplace. Carson, who is African-American, had a fabled medical career at Johns Hopkins in Baltimore, during which he never openly engaged in politics. Even now, as a declared presidential candidate, he boasts of never using notes or a prepared text, simply speaking off the cuff.

Carson was promoted among Tea Party Republicans after a televised confrontation with President Obama in 2013 during the National Prayer Breakfast in Washington, in which he denounced the Affordable Care Act and advocated a “flat tax” that would substantially cut taxes for the wealthy and corporations. The Wall Street Journal immediately published an editorial headlined “Ben Carson for President,” and a National Draft Ben Carson for President Committee raised $16 million.

In subsequent months Carson went on to claim that Obamacare was the “worst thing to have happened in this nation since slavery” and to suggest that Obama was a “psychopath” and that Christians faced repression in the United States “very much like Nazi Germany.” He published a 2014 book,One Nation, denouncing the decline of moral values in America and appealing to Christian fundamentalists and anti-gay bigots.

Carson’s opposition to welfare programs and his law-and-order demagogy took a blow from the recent events in Baltimore, the city where he made his name as a surgeon and medical administrator. He has been silent on the police violence that triggered days of unrest, while claiming that rioters saw looting as an economic opportunity.

Multi-millionaire former CEO Carly Fiorina announced her candidacy Monday as well, using video posted on the Internet as well as media interviews. Like Carson, she has never held political office, but she has been active in Republican Party politics since being fired by Hewlett-Packard in 2005. She was the Republican candidate for US Senate in California in 2010, losing to incumbent Democrat Barbara Boxer, and served as an adviser and campaign surrogate for Republican presidential nominee Mitt Romney in 2012.

Fiorina claims that her top qualification is knowing “how the economy actually works” and that her role as a CEO showed she could make “a tough call in a tough time with high stakes.” Her corporate experience does indeed personify the state of the American economy, as she oversaw the cutting of 36,000 jobs at H-P and then received a $21 million golden parachute from the company when she eventually lost the confidence of the board of directors and was ousted, after a merger with rival Compaq failed to boost profits sufficiently.

Fiorina’s campaign appears to be an audition for running mate rather than for the top spot on the Republican ticket, as she has focused largely on strident public attacks on the likely Democratic nominee, Hillary Clinton, the role traditionally played by a vice-presidential nominee. She is acceptable to the military-intelligence apparatus, having served two years as chair of the CIA’s External Advisory Board, from 2007 to 2009.

Like Carson and many of the other Republican hopefuls, Fiorina is prone to bizarre utterances, as when she told Time magazine that liberal environmentalists were responsible for the massive drought now afflicting California.

The third Republican to declare his candidacy this week, former Arkansas Governor Mike Huckabee, ran for president previously in 2008, winning the Iowa caucus thanks to support from Christian fundamentalists and home-schoolers, and also winning seven primaries in the South. He had to halt his campaign after financial support dried up, but was the last rival to concede to the eventual Republican nominee, John McCain.

Since then, Huckabee has become a multimillionaire talk-show host on Fox News, raking in additional income with a radio program and books marketed to the ultra-right audience, and by serving as a pitchman for a dubious series of commercial products, including a quack remedies for diabetes. Like Bill Clinton, he has risen from poor beginnings in Hope, Arkansas—they were both born in the same small town—to living in a mansion, although in Huckabee’s case it is on the Florida Gulf coast rather than in the New York City suburbs.

As a largely flattering profile on Politico.com described him, Huckabee is now “a part of the one percent. There’s the 10,900-square-foot beachfront mansion he built on Florida’s Panhandle, worth more than $3 million. There are regular trips on private jets, often to elite events at which he has given countless paid speeches.”

While likely to have an impact again in the Iowa caucus and Southern primaries, Huckabee faces more competition for the Christian fundamentalist vote than in 2008. He has accordingly sought to outbid rivals like Cruz, former senator Rick Santorum and Louisiana Governor Bobby Jindal, suggesting that Obama was against Christians and Jews but gave his “undying, unfailing support” to the Muslim community. He has also been the most strident Republican opponent of gay marriage and abortion.

This is combined with a right-wing populist attack on New York-based financial interests, denouncing “the real axis of evil in this country—the axis of power that exists between Washington and Wall Street.” He has come close to the language of the AFL-CIO in opposing the Trans-Pacific Partnership trade deal, where he declared that among American CEOs, “We have a lot of globalists and, frankly, corporatists instead of having nationalists.”

This type of right-wing populist demagogy is a political show aimed at confusing workers and lining them up behind the interests of their “own” capitalists on the basis of economic nationalism. It serves the interests of the financial aristocracy and the military-intelligence apparatus, which is preparing for stepped-up military adventures overseas.