Andre Damon

On Monday, Google, the internet search and smartphone software monopoly, announced that it would block Huawei phones from accessing critical parts of the Android operating system, effectively ending Huawei’s business outside China.

Compounding the blow, US hardware manufacturers Qualcomm, Broadcom and Intel announced that they would no longer sell the company components, without which it cannot produce any of its current line of smartphones or IT infrastructure systems.

The moves came after the US Department of Commerce added Huawei to its Restricted Entity List on the grounds that it was “engaged in activities that are contrary to US national security or foreign policy interests.”

The companies complied with Trump’s nakedly protectionist measure, which has serious consequences for their own business interests, without a hint of protest. Whatever damage Trump’s trade war does to their bottom line will be more than offset by winning the favor of the American state and securing preferential regulatory treatment and lucrative military contracts worth billions of dollars.

Huawei announces the Mate X folding smartphone in February

Huawei announces the Mate X folding smartphone in February

In a nervous editorial, reflecting the hesitations of the British ruling class over the US war on Huawei, the Financial Times did not mince words. The US was afraid that China’s “technology is on course to outstrip America’s,” it wrote. The newspaper concluded bluntly, “Indeed, the US steps appear part of an attempt to constrain China’s rise.”

With sales of Apple and Samsung phones plunging, Huawei was on the verge of becoming the largest seller of smartphones by the end of the year, in addition to being the world’s leading provider of 5G telecommunications equipment.

In the course of just a few years, Huawei has become the most dynamic player in the highly competitive and rich global smartphone market. Its phone sales have risen 50 percent over the past 12 months.

Huawei has not only produced the top-ranked phone camera, according to DxOMark, for two generations in a row. With the botched launch of Samsung’s Galaxy Fold, Huawei is also on the verge of rolling out the first viable mass market phone that converts into a tablet, dominating a market segment that Apple, the previous industry leader, has not even attempted to enter.

However, the blacklisting of Huawei by the Trump administration, and the cooperation of Google and other major technology companies, will mean the effective destruction of Huawei as a player in the global smartphone market. Even if it is able to produce phones without relying on components sold by American companies, their sales will be confined to the Chinese market. The moves, one analyst told the Financial Times, were “very likely to cost Huawei all of its smartphone shipments outside China.”

No one knows what the consequences of this new salvo in the global trade war will be. The development of the internet and the launch of the app economy by Apple in 2007 took place during a period of globalization and international integration. However, the internet and the global technology industry are becoming fragmented along national boundaries, amid the rise of protectionism and trade war.

In a clear-eyed warning about the potential implications of the breakdown in US-China relations, Morgan Stanley predicted that despite a loosening of monetary policy by the Fed, the move against Huawei would likely portend a “full-blown recession” in the United States.

The announcement by the White House last week of new restrictions on Huawei and Google’s compliance with them come after the near total failure of US efforts to prevent its allies from purchasing Huawei communications equipment. Britain, Germany, India and numerous other countries rejected Washington’s efforts to strong-arm them into banning Huawei’s 5G telecommunications equipment, which is universally regarded as substantially superior to its Western competitors.

In response, the US simply doubled down, leading to what one analyst told the Financial Times was “effectively the starting signal of a technology cold war.” The New York Times called the move the beginning of a “digital iron curtain.”

The massive and sudden intensification of the US-China trade war came as a shock for many. “The move by the Trump administration is much more comprehensive than many Chinese expected,” one analyst told the Times … “It also came much earlier. Many people only realize now that it’s for real.”

The growing conflict between the United States and China is centered on US efforts to prevent the entry of Chinese corporations into high-value manufacturing segments previously dominated by the US and EU members such as Germany. Last year, the Trump administration shortened visa durations for Chinese graduate students studying in fields such as robotics, aviation and hi-tech manufacturing. Meanwhile a group of congressional lawmakers is pushing for even further restrictions on student visas.

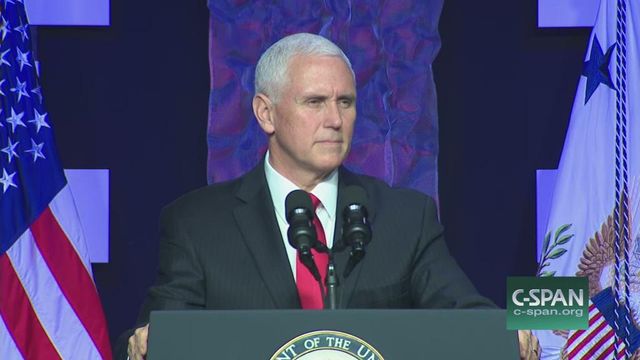

US Vice President Mike Pence

US Vice President Mike Pence

In November, Vice President Mike Pence announced what many called a new Cold War between the United States and China, demanding that China abandon its efforts to enter into “the world’s most advanced industries, including robotics, biotechnology, and artificial intelligence,” which he called the “commanding heights of the 21st century economy.”

Since then, US and Chinese negotiators had intensively discussed a possible deal to halt the raging trade war. But the discussions fell apart, once it became clear to Chinese negotiators that the United States was demanding what China could not offer: the effective dismantling of its high-tech manufacturing sector.

Commenting on last week’s announcement, the China Daily declared: “With its treatment of Huawei, the US government has revealed all its ugliness in its dealings with other countries: its despotism as the world’s sole superpower without any respect for rules, its haughtiness and lack of respect for the dignity of its trade partners, its condescending attitude toward the rest of the world and its outright selfishness and unwillingness to accept that it is a member of a wider community.”

But could China’s ruling elite have expected otherwise? American imperialism was happy to make China the sweatshop of the world, extracting billions of dollars from the toil of its proletariat. The US, however, will not abide China becoming an economic peer and will use all its power—from its preeminent role in the global financial system, to its network of alliances, to the threat of full-blown nuclear war—to assert its dominance.

The US attempt to destroy Huawei is only a preview of how far it will go to secure its hegemony. The country that brought the world Hiroshima, Vietnam and the Iraq war is willing to destroy more than just companies. It is now setting its sights on a country of 1.4 billion people, with potentially devastating consequences for all of humanity. China, for all its vaunted economic growth, remains an oppressed country in the crosshairs of imperialism.

These developments should put to rest the fashionable academic arguments that the categories of Marxism—imperialism, monopoly, exploitation, and the conflict between the global economy and nation-state system—have been superseded. In fact, it is only these analytical tools that explain the fragmentation of the global economy in the 21st century and the reemergence of “great-power conflict.”

The central argument of contemporary Marxism, made abundantly clear by the 20th century, is that socialist revolution is the only way to avoid a new global conflagration, driven by the desperate struggle between capitalist nation-states for markets, profits and influence.