Frank Gaglioti

The discovery of a nearly complete australopithecine skull has greatly extended our understanding of the earliest period of human evolution. The fossil find was reported on August 28 in the science journal Nature in a paper titled “A 3.8-million-year-old hominin cranium from Woranso-Mille Ethiopia.” Hominins include modern humans and all species considered ancestral to them.

Australopithecus, or southern apes, emerged in Africa around Ethiopia, Kenya and Tanzania about four million years ago and are known to have survived to two million years ago. They had a small brain similar in size to a chimpanzee, but had a hand with an opposable thumb enabling them to use tools. This is considered to be the crucial feature diagnostic of humans. The use of tools led over millions of years to the development of a larger brain and other traits such as language.

Over this period, the east African climate was drying out, leading to the shrinking of the forested areas. Australopithecus were an evolutionary adaptation to the new conditions, as they evolved to walking upright rather than dwelling in trees.

Yohannes Haile-Selassie, PhD with “MRD” cranium. Photograph courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History.

Yohannes Haile-Selassie, PhD with “MRD” cranium. Photograph courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History.

The discovery of a nearly complete skull from this period is incredibly rare. It will enable a reassessment of what is known of the earliest period of hominin evolution, particularly the development of the australopithecine species and their development into true humans.

The lead scientist was Yohannes Haile-Selassie, a paleoanthropologist from Cleveland Museum of Natural History, aided by a researcher from the Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Anthropology Stephanie Melillo.

The upper jaw was originally discovered by a local goat herder, Ali Bereino, from the Mille district of the Afar Regional State. After Haile-Selassie examined the site he found the upper part of the skull three metres away.

“I couldn’t believe my eyes when I spotted the rest of the cranium. It was a eureka moment and a dream come true,” said Haile-Selassie.

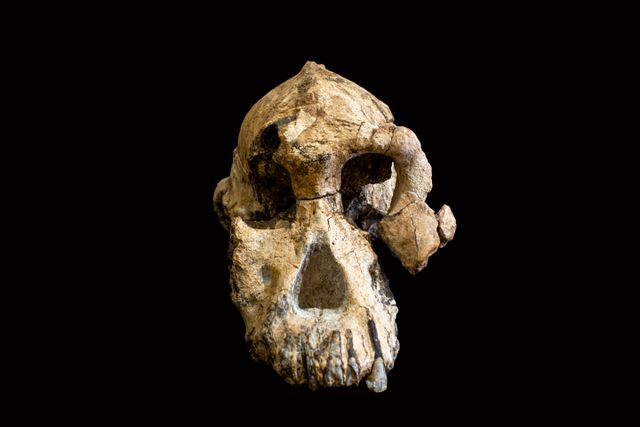

“MRD” cranium, photographed by Yohannes Haile-Selassie, PhD. Courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History.

“MRD” cranium, photographed by Yohannes Haile-Selassie, PhD. Courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History.

The fossil has been named MRD-VP-1/1 or MRD. It has been designated as Australopithecus anamensis through a detailed examination of the jaw and teeth. The name derives from anam—the word for lake in the Turkana language, spoken in north west Kenya.

The skull most likely belonged to an adult male. It has wide cheekbones, a long protruding jaw and a large canine tooth. The scientists used micro-CT scans and 3D reconstructions in order to definitively identify the species.

“Features of the upper jaw and canine tooth were fundamental in determining that MRD was attributable to A. anamensis … It is good to finally be able to put a face to the name,” said Melillo.

The Woranso-Mille site in central Afar is rich in fossils and palaeontologists have been exploring the area since 2004. They have discovered 12,600 fossil specimens from 85 mammalian species and 230 hominin fossils dated from 3.8 to 3.0 million years ago.

A. anamensis is considered to be the direct ancestor of A. afarensis made famous after Donald Johanson’s discovery of the almost complete skeleton of “Lucy” in 1974. A. afarensis is thought to have led directly to Homo, or true human species. The transition from A. anamensis to A. afarensiswas believed to have occurred 2.8 million years ago.

The cranium specimen from the front. Photograph(s) by Dale Omori, courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History.

The cranium specimen from the front. Photograph(s) by Dale Omori, courtesy of the Cleveland Museum of Natural History.

MRD’s age suggests that A. anamensis and afarensis lived contemporaneously for 100,000 years, making this early period of human evolution more complex than previously thought.

Paleoanthropologist Meave Leakey originally named A. anamensis in 1994 from teeth and bone fragments discovered in Kenya. An earlier, previously unnamed specimen of an arm bone indicated a tree climbing existence. A. anamensis has features of the more advanced A. afarensis as well as more primitive features at the same time. The discovery of MRD enables the consolidation of the species designation.

Haile-Selassie and his team believe that it is highly probable that A. anamensis did evolve into A. afarensis. This likely occurred due to the isolation of a small group of A. anamensis that made the transition to A. afarensis, which then became the dominant species. However, the original A. anamensis species was able to survive for some time longer.