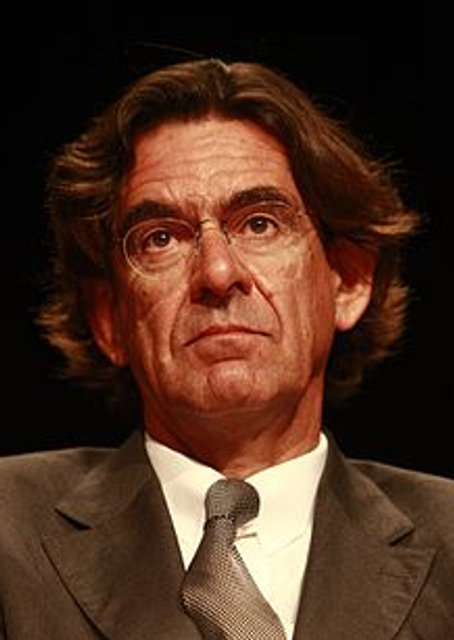

Cesar Chelala

Harvey Weinstein never imagined that actresses’ complaints against his abusive behavior would trigger a worldwide movement for women’s justice and fair treatment by men. Despite continued acceptance of physical and sexual violence against women, both women and men are now organizing across cultures and socioeconomic classes to challenge and change gender-based abuse and injustice.

Recently, in Argentina, the denunciation by actress Thelma Fardin that she was raped by the well-known Argentine actor Juan Darthés when she was 16 and he was a 45-year-old man forced him to leave the country in shame. In Sao Pablo, Brazil, where Darthés was hired to work in a restaurant, he was met by the loud complaint of a large group of Brazilian women.

Worldwide, the most common kind of gender violence is domestic violence, which occurs in the home or within the family. It affects women regardless of age, education or socioeconomic status. Although generally women are the victims, men are also abused by their wives or partners. Violence also occurs among same-sex partners.

Although physical violence and sexual violence are easier to see, other forms of violence include emotional abuse, such as verbal humiliation, threats of physical aggression or abandonment, economic blackmail and confinement at home. Many women report that psychological abuse and humiliation are even more devastating than physical violence because of the negative long-lasting effects on their self-confidence and self-esteem.

In many countries violence against women, especially in the domestic setting, is seen as acceptable behavior. Even more disturbing, a large proportion of women are beaten while they are pregnant. Comparative studies reveal that pregnant women who are abused have twice the risk of miscarriage and four-times the risk of having low-birth-weight babies than non-battered pregnant women.

Extent of the problem

Few precise figures on violence against women exist, but existing numbers are shocking. In every country where reliable studies have been conducted, statistics show that between 10% and 50% of women report that they have been physically abused by an intimate partner during their lifetime.

According to Mexico’s Health Ministry, about one in three women suffer from domestic violence, and it is estimated that over 6,000 women in Mexico die every year as a result. A study of women in Mexico sponsored by the government (Encuesta Nacional sobre la Dinámica de las Relaciones en los Hogares 2006), reported that 43.2% of women over 15 years old have survived some form of intra-family violence over the course of their last relationship.

Domestic violence is rife in many African countries as well. In Zimbabwe, according to a United Nations report, it accounts for more than six in ten murder cases in court. According to surveys, 42% of women in Kenya and 41% in Uganda reported having been beaten by their partners. Although some countries such as South Africa have passed women’s rights legislation, the big test — full implementation, with teeth — has not been passed.

In China, according to a national survey, domestic violence occurs in one-third of the country’s 270 million households. A survey by the China Law Institute in Gansu, Hunan and Zhejiang provinces found that one-third of the surveyed families had witnessed family violence and that 85% of victims were women.

In Japan, as in many other countries, the number of reported cases has increased in recent times. According to some advocates working to end domestic violence, this may signal that survivors may be overcoming cultural and social taboos that once forced them into silence. According to the National Police Agency, the number of consultations with the police from survivors of domestic violence in 2017 rose 3.6 percent compared to the previous year to reach a total of 72,455.

In Russia, estimates put the annual domestic violence death toll at more than 14,000 women. Natalya Abubikirova, executive director of the Russian Association of Crisis Centers, in a statement to Amnesty International, drew a dramatic parallel to capture the scope of the problem, “The number of women dying every year at the hands of their husbands and partners in the Russian Federation is roughly equal to the total number of Soviet soldiers killed in the 10-year war in Afghanistan.”

In a study conducted by the Council for Women at Moscow State University, 70% of the women surveyed said that they had been subjected to some form of violence — physical, psychological, sexual or economic — by their husbands. Some 90% of respondents said they had either witnessed scenes of physical violence between their parents when they were children or had experienced this kind of violence in their own marriages.

Research carried out in several Arab countries, indicates that at least one out of three women is beaten by her husband. Despite the serious consequences of domestic violence, and the increasing frequency of violence against women, not enough is done by the governments of Arab and Islamic countries to address these issues. “To date, there is no comprehensive and systematic mechanism for collecting reliable data on violence against women in Arab countries,” states the United Nations Development Fund for Women (UNIFEM).

In many Islamic countries, or in countries with a substantial Muslim majority, passages from the Koran are sometimes used to justify violence against women. Yet many religious experts state that Islam rejects the abuse of women and advocates equality in the rights of women and men. In many cases, violence against women — including killings — are based more on cultural than religious grounds and are justified by the need to protect a family’s honor.

There is no single factor that accounts for violence against women, but several social and cultural factors have kept women particularly vulnerable to this phenomenon. What they have in common, however, is that they are manifestations of historically unequal power relations between men and women. In Latin America, a culture of machismo often gives license for such abuses.

When this kind of relationship becomes established, people become conditioned to accept violence as a legitimate means of settling conflicts — both within the family and in society at large — thus creating and perpetuating a vicious cycle.

Women who marry at a young age are more likely to believe that sometimes it is acceptable for a husband to beat his wife, and are more likely to experience domestic violence than women who marry at an older age, according to a UNICEF study.

Lack of economic resources and the capacity to lead economically independent lives also underscore women’s vulnerability to violence, and the difficulties they face in extricating themselves from a violent relationship.

Consequences of violence against women

Worldwide, violence is as common a cause of death and disability among women of reproductive age as cancer. It is also a greater cause of ill health than traffic accidents and malaria together. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) violence against women claims almost 1.6 million lives each year — about 3% of deaths of all causes.

What’s more, sexual violence increases women’s risk of contracting sexually transmitted diseases, including AIDS (through forced sexual relations or the difficulty in persuading men to use condoms), increases the number of unplanned pregnancies, and may lead to various gynecological problems such as chronic pelvic pain and painful intercourse.

According to the WHO’s “World report on violence and health,” between 40% and 70% of female murder victims in Australia, Canada, Israel, South Africa, the United Kingdom, and the United States were killed by their husbands or boyfriends — often within the context of an ongoing abusive relationship.

Studies conducted in the United States reveal that each year approximately 4 million women are physically attacked by their husbands or partners. One U.S. study concludes that violence against women is responsible for a large proportion of medical visits, and for approximately one-third of emergency room visits. Another study found that in the United States, domestic violence is the most frequent cause of injury in women treated in emergency rooms, more common than motor vehicle accidents and robberies combined.

In the United States, 25% of female psychiatric patients who attempt suicide are survivors of domestic violence, as are 85% of women in substance abuse programs. Studies carried out in Pakistan, Australia and the United States show that women survivors of domestic violence suffer more depression, anxiety, and phobias than women who have not been abused.

Domestic violence can have devastating consequences on children as well. According to a UNICEF report, as many as 275 million children worldwide are currently exposed to domestic violence. One of the findings of the report is that children who witness domestic violence not only endure the stress of an atmosphere of violence at home but are more likely to experience abuse themselves.

It is estimated that 40% of child-abuse victims also have reported domestic violence at home. In addition, children who are exposed to domestic violence are at greater risk for substance abuse, teenage pregnancy, and delinquent behavior.

Although doctors and health personnel can greatly help the victims, many times they are not trained to diagnose abuse accurately. And women are often reluctant or afraid to report abuse.

Various cultural and socioeconomic factors, including shame and fear of retaliation, contribute to women’s reluctance to report these acts. Legal and criminal systems in many countries also make the process difficult. Currently, in the U.S., the fear of deportation has kept many immigrant women, particularly from Central America, from denouncing violence at the hands of their husbands and partners. Men threaten to report women to immigration authorities should they seek legal assistance.

Frequently, fear keeps women trapped in abusive relationships. It has been found that almost 80% of all serious gender violence injuries and deaths occur when female survivors of violence attempt to leave a relationship — or after they have left.

Preventing violence against women

Governments and Non-Governmental Organizations (NGOs) have been increasingly responsive to women groups’ demands to deal seriously with this issue. In Bangladesh, new laws make violence against women a punishable offense. Belgium, Peru, and Yugoslavia have amended laws to more clearly define sexual harassment.

The Dominican Republic, Portugal, Spain, Uruguay, and Belgium, among others, have passed laws that increase penalties for domestic abuse. The Kingdoms of Jordan and Morocco have made strides to protect women’s rights — denouncing so-called honor killings in the former and providing confidential victims’ assistance hotlines in the latter.

In India and Bangladesh, a traditional system of local justice called salishe is used to address abuse on a case-by-case basis. For example, when a woman is beaten in Bangladesh, the West Bengali non-governmental organization Shramajibee Mahila Samity sends a female organizer to the village to discuss the situation with the people involved and helps find a solution, which is then formalized in writing by a local committee.

In China, there has been some progress regarding this issue as well, such as placing posters on some roads and in subways stressing the problems that domestic violence represents to society. The All-China Women’s Federation has been playing a significant role in bringing domestic violence into the legislative and policy-making processes.

Given the difficulties in properly diagnosing abuse or reluctance report it, prevention of violence against women is a key strategy. As a World Health Organization report states, “The health sector can play a vital role in preventing violence against women, helping to identify abuse early, providing victims with the necessary treatment and referring women to appropriate and informed care. Health services must be places where women feel safe, are treated with respect, are not stigmatized, and where they can receive quality, informed support.”

Studies carried out in industrialized countries shows that public health preventive approaches to violence can lower the negative impact of domestic violence. Prevention acts at three levels: primary prevention stops the problem from happening; secondary prevention stops it from progressing further; and tertiary prevention teaches survivors, after the fact, how to avoid its repetition. In England, primary prevention strategies have included educating children and youth in schools and community centers about effectively managing challenging emotions such as anger and frustration which can lead to violence. Lessons also focus on promoting positive gender relations and healthy self-esteem which can mitigate violence,

Many governments find it difficult to work with women at the community level, which is where NGOs come into play. This is the case in Jamaica, Malaysia, and Mozambique, among others, where these organizations have been particularly active. In Ethiopia, the Association of Women’s Lawyers is actively working against sexual violence and domestic abuse.

However, more work needs to be done if this pandemic is going to be controlled. Government and community leaders should spearhead an effort to create a culture of openness and support to help eliminate the stigma associated with women victims of violence. Also, stricter laws should be enacted and enforced, followed up with plans for specific national action.

In the U.S., the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention has devised a set of strategies to help control this kind of violence through a technical package of programs, policies, and practices. Because it has a comprehensive approach, its use can have a definite effect in lowering the considerable burden of intimate partner violence.

The involvement of men is also critical to curb the spread of violence. In this case, also, NGOs have proven to be more effective than government agencies. In Cambodia, Jamaica and the Philippines, NGOs are working effectively with men to support women’s empowerment and rights. The Women’s Centre of the Jamaica Foundation counsels young male parents and trains male peer educators through its program Young Men at Risk.

Domestic violence is a threat to equality and justice. Forced out of the shadows and into the light, violence against women is finally being addressed worldwide, but efforts need continued attention and mobilization in order to succeed in the long term.

César Chelala is an international public health consultant and a winner of several journalism awards. He is the author of “Violence in the Americas” and “Maternal Health”, both publications of the Pan American Health Organization.