Robert Stevens

The Conservative government has enforced the cruel deportation of around 20 people to Jamaica. The flight had originally been specified to deport up to 56 people but late Monday night the Court of Appeal ordered the halting of deportations to some of those on board—after ruling that their democratic rights, including their right to access legal advice, had been flagrantly breached.

The flight was originally scheduled to leave the UK today from Heathrow Airport at around 6:30 a.m but in the end it was not revealed where the flight departed from or when it left. The men on board were among 700 immigrants, refugees and asylum seekers being held at two immigration detention removal centres near Heathrow Airport—Colnbrook and Harmondsworth.

The Court of Appeal ruled in a case brought against the Home Office by Duncan Lewis solicitors on behalf of the Detention Action charity last week. The charity argued that due to the O2 mobile phone network being unavailable in the area immediately next to Colnbrook and Harmondsworth, detainees were denied the right to have five working days to contact and instruct lawyers after receiving notice from the Home Office that they were to be deported on the Tuesday flight.

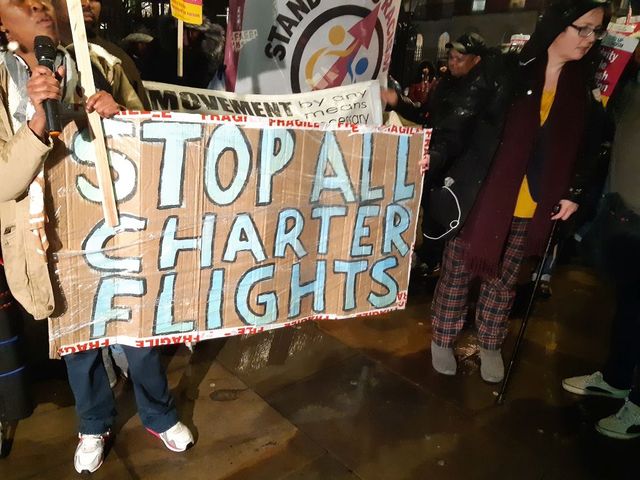

Protesters outside Downing Street

Protesters outside Downing Street

The ruling did not oppose all the deportations being carried out in principle, instead Lady Justice Simler ordered the Home Office not to remove anyone from Harmondsworth or Colnbrook for deportation “unless satisfied (they) had access to a functioning, non-O2 Sim card on or before February 3”.

Director of public law at Duncan Lewis, Toufique Hossain, who brought the case said, “For weeks now detainees’ complaints have fallen on deaf ears. Their removal looms large, hours away and yet again it takes judicial intervention to make the home office take basic, humane and fair steps to allow people to enjoy their constitutional right to access justice.”

Despite the Court of Appeal ruling, it is still not clear who was on the flight with Chancellor Sajid Javid telling BBC 5 Live Tuesday morning he did not know the exact number but understood it was “around 20--or above 20.”

The Court of Appeal decision was made as hundreds of people demonstrated outside Downing Street Monday evening. Among their chants were “Stop charter flights! We want human rights!” Home-made placards demanded, “Amnesty for All. No More Tearing Families Apart” and “Jamaican government stop colluding with UK government racist charter flights”.

The move to deport the men met with widespread public outrage. An online petition to “Stop all charter flight deportations to Jamaica and other Commonwealth countries” received over 100,000 signatures by the end of Monday evening, with hundreds signing every few minutes.

This surge in opposition no doubt had its impact on the Court of Appeal decision.

Protesters outside Downing Street

Protesters outside Downing Street

Those to be deported at Harmondsworth and Colnbrook were being held in a state of mental torture, not knowing their fate and waiting to be bundled onto a flight at any time. The Independent reported that “some of those earmarked for deportation were told it would take place on 6 February…” before it was switched to this week.

The Tory government were determined to ram through the deportations in breach of the law, with Boris Johnson confirming in Parliament at last week’s Prime Minister’s Question Time that the deportations would go ahead. His statement led to hundreds protesting last Thursday outside Downing Street and shutting down the adjacent main street, Whitehall.

In Parliament Monday, Home Secretary Priti Patel insisted that the flight would still depart Tuesday and repeated that those being deported had committed “serious offences.” This was in the face of opposition from 170 MPs and peers who signed a letter calling on the government to halt the flight, and a legal bid, also by Duncan Lewis Solicitors, representing 15 people due to be deported.

On Monday, they filed papers at the High Court calling for an urgent oral hearing that afternoon to discuss the matter. They argued that Patel was acting unlawfully by forcing the men onto the plane, had denied them adequate access to legal advice and breached human rights legislation. The adverse publicity around the deportations and their labeling as “serious criminals” by the UK government would ensure the men would be a “public spectacle” on arrival in the Jamaican capital, Kingston, endangering their safety.

Late Monday afternoon, High Court judge Justice Mostyn refused Duncan Lewis’ application on behalf of 13 Jamaican-born men and refused to halt the flight. By Monday evening the grounds for refusing that application had not been revealed.

The forced deportation of the Jamaican nationals, many of whom have lived in the UK for years, is an escalation of the Tory government’s anti-immigrant agenda following the UK’s exit from the European Union on January 31. One is a 30-year old who has lived in the UK since the age of 11 and another 24 years old and has lived in Britain since he was 4 years old.

Protesters outside Downing Street

Protesters outside Downing Street

The government carried out the deportations on the basis of Johnson’s deliberately incendiary words that it “is right to send back foreign national offenders.” This was followed by a statement from chief secretary to the Treasury, Rishi Sunak, who said Monday, “Many of these people have committed crimes such as manslaughter, rape, other very serious offences.”

No-one can take these lurid claims at face value. A year ago this month, the Tory government deported 29 people on a flight to Jamaica after making identical claims. Then Home Secretary and now Chancellor Sajid Javid faced calls to apologise after saying those on board that flight were all convicted of “very serious crimes... like rape and murder, firearms offences and drug-trafficking.”

Following the deportations, the Home Office was forced to admit this was not the case at all as it emerged that just one person on board had committed a serious crime, murder. Some 14 of those deported had been convicted of drug offenses and one had been jailed for dangerous driving.

According to the Home Office, those it deported yesterday and those who it was unable to deport, for now--due to the Court of Appeal ruling--all have criminal convictions. However, even if this is the case, they have served their sentences in the UK and are being punished again with deportation to a country that many left as young children.

One of those who may have been on the plane Tuesday is 30-year-old Reshawn Davis, a father of a six-month-old baby, married to his British wife for five years. Davis was arrested only last Friday and informed by Home Office officials that he would be deported after they found out he had spent just two months in prison over a decade ago.

Davis was convicted under the controversial “joint enterprise” law, historically used to convict people in gang-related cases if defendants “could” have foreseen violent acts by their associates. The Supreme Court ruled in 2016 that the law had been wrongly interpreted for 30 years.

Speaking to the Independent he said, “I’m so stressed out. I can’t even explain how I feel. Yes, I was born in Jamaica, but I was brought up here. I don’t know anything else. I made one mistake in life, and it feels like I tried to kill the Queen.”

If Davis was deported--along with the 55 others threatened--his child will be one of 41 children who will be deprived of their fathers. He said of his daughter, “I look at my daughter’s pictures now every night before I go to bed. Since she was born, I had never spent a night without her until I was locked in here. I still reach for her when I wake up.”

The government was determined to carry out the deportations in breach of human rights legislation and international law, as people cannot be deported if their life could be in danger by doing so. Davis added, “I’m terrified to go to Jamaica. My cousin was deported and he has now died. People will be hostile to me because I’ve been deported. I’m going to be targeted.”

The Home Office keeps no records on the wellbeing of those it deports, but the Guardian established last May through its own research that five people previously deported have been murdered in Jamaica since March 2018. Jamaica has one of the highest per capita murder rates of any country.

One of those murdered was a 37-year-old, Dewayne Robinson. Robinson was the cousin of Akeem Finlay, 30, who came to the UK aged just 10. Not only had one of his cousins been murdered, but just months prior to Robinson’s killing another cousin of Finlay’s was killed. Before being granted a last-minute reprieve in a separate court case, Finlay was to have been deported Tuesday on the basis of a previous Grievous Bodily Harm conviction. Finlay said, “The men involved in the murders of my cousins have warned our family not to return to Jamaica or we will be murdered too.”

The threat of deportation still hangs over all 56 and many others. It would be a grave mistake to rely on the courts or the politicians of parties who are responsible for the huge assault on immigrants now underway. The Tories are only able to proceed with such a sadistic policy because they can rely on legislation brought in by the Blair Labour government. Under the UK Borders Act 2007, a deportation order must be made if a foreign national has been convicted of an offence and received a custodial sentence of just 12 months or more.

The letter signed by the 170 MPs and peers was organised by Labour MP Nadia Whittome and did not call for an end to deportations in principle, but only that Tuesday’s flight and other deportations be halted until a review into the Windrush scandal is published and “its recommendations implemented.”

The letter welcomed the sight of a leaked version of the review, which states the government “should consider ending all deportations of FNOs [foreign national offenders] where they arrived in the UK as children (say before age of 13)” before adding, “Alternatively—deportation should only be considered in the most severe cases.”

The Windrush scandal refers to some 164 people detained and deported to Commonwealth countries and 5,000 denied access to support from public services to which they were fully entitled. According to the government’s own figures, by November 2018 at least 11 deportees had subsequently died.