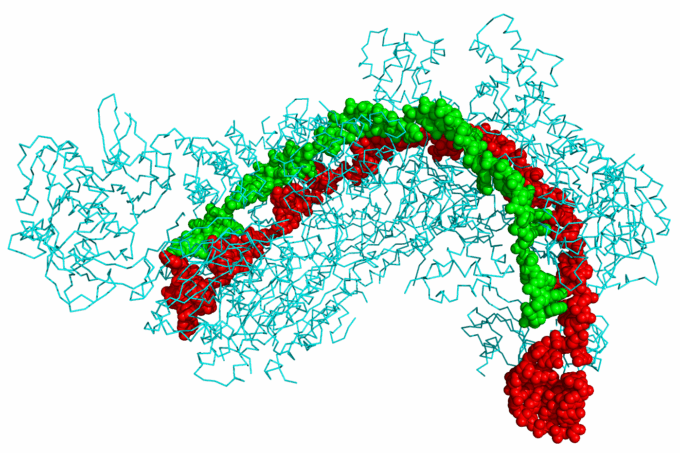

Crystal structure of a CRISPR RNA-guided surveillance complex. Image Source: Boghog – CC BY-SA 4.0

A major medical milestone took place in May 2025, when doctors at the Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia used CRISPR-based gene editing to treat a child with a rare genetic disorder. Unlike earlier CRISPR (Clustered Regularly Interspaced Short Palindromic Repeats) treatments that targeted well-known genetic mutations, this marked a new level of personalized medicine tailored to a patient’s unique DNA. For advocates of biomedical innovation for human enhancement, it was another sign of gene editing’s vast potential, even as ethical, political, and safety concerns remain.

Efforts to alter human genes really began in the 1970s, when scientists first learned to cut a piece of DNA from one organism and attach it to another. The process was slow, imprecise, and expensive. Later tools like meganucleases, transcription activator-like effector nucleases, and zinc-finger nucleases improved accuracy but remained technically complex and time-consuming.

The real revolution came in 2012, when researchers Jennifer Doudna and Emmanuelle Charpentier harnessed CRISPR, a natural bacterial defense system. In bacteria, CRISPR cuts out invading viruses’ DNA and inserts fragments into its own genome, allowing it to recognize and defend against future infections. Doudna and Charpentier showed that this process could be adapted to any DNA, including human, creating a precise and programmable system to target genetic mutations. Together with a protein called CRISPR-associated protein (Cas9), which acts like molecular scissors, it made cutting, modifying, and replacing DNA faster, easier, and cheaper.

Attempts to push the technology forward clashed with regulatory caution and ethical debate, but more than 200 people had undergone experimental CRISPR therapies, according to a 2023 MIT Technology Review article. The first major legal breakthrough came that November, when the UK approved Vertex Pharmaceuticals’ CASGEVY for the treatment of transfusion-dependent beta thalassemia and sickle cell disease. Enabled by advances in CRISPR technology, CASGEVY works by making “an edit (or ‘cut’)… in a particular gene to reactivate the production of fetal hemoglobin, which dilutes the faulty red blood cells caused by sickle cell disease,” explained Yale Medicine. Bahrain and the U.S. granted regulatory approval weeks later, and by mid-2025, the EU and several other countries followed.

CRISPR technology continues to advance, with researchers at the University of Texas at Austin recently unveiling a CRISPR therapy that can replace large defective DNA segments and fix multiple mutations simultaneously, overcoming the limits of traditional one-site editing. “Epigenetic editing,” meanwhile, uses modified Cas9 proteins to turn genes on or off without cutting the DNA, and new CRISPR systems can even insert entirely new DNA directly into cells, bypassing the cell’s natural repair process for larger precision edits.

Alongside academic researchers, major companies are emerging in the gene-editing field. By early 2025, the U.S. had 217 gene-editing companies, compared with a few dozen in Europe (mainly in the UK and Germany) and 30 in China, according to the startup company BiopharmaIQ.

CRISPR Therapeutics, Intellia Therapeutics, and Beam Therapeutics are among the industry’s leaders. A growing network of companies and research teams attended the Third International Summit on Human Genome Editing held in London in 2023, following the first in Washington, D.C., in 2015, and the second in Hong Kong in 2018.

Smaller companies are also innovating. Xenotransplantation—

The patient survived for two months before dying of unrelated causes, and the company completed another transplant in 2025. Other companies, including United Therapeutics through its subsidiary Revivicor, have begun their own trials in a potential bid to transform the organ donor industry.

CRISPR’s rapid spread has also fueled a DIY biotech movement among transhumanists and bioha

“[N]ew technologies such as CRISPR/Cas9 give nonconventional experimenters more extensive gene editing abilities and are raising questions about whether the current largely laissez-faire governance approach is adequate,” pointed out a 2023 article in the Journal of Law and the Biosciences.

One of the best-known figures in this movement is former NASA biochemist Josiah Zayner, who founded The ODIN in 2013 to sell CRISPR kits “to help humans genetically modify themselves.” Early efforts to showcase the scope and potential of this technology proved popular online, and in 2017, Zayner livestreamed injecting CRISPR-edited DNA to knock out his myostatin gene to promote muscle growth.

CRISPR has quickly expanded beyond human experimentation. Mississippi dog breeder David Ishee attempted to get regulatory approval for CRISPR technology to prevent Dalmatians’ tendency to develop bladder stones in 2017, but faced immediate regulatory pushback. The agriculture sector has seen more luck: U.S. startup Pairwise has developed a CRISPR-edited salad mix for American consumers, and in 2024, a multinational biotech consortium began pilot trials of drought-resistant maize in Africa.

China has been a leading force in CRISPR innovation since its inception. In 2014, Chinese researchers were among the first to use CRISPR-Cas9 in monkey embryos, and became the first to edit human embryos in 2015, drawing concern from international observers. In 2018, Chinese researcher He Jiankui altered the DNA of two human embryos to make them immune to HIV. Although the babies were born healthy, the announcement caused international outcry, leading to He’s three-year prison sentence in 2019 and stricter Chinese regulations on human gene editing.

Chinese companies and institutions are actively pursuing international collaboration to solidify their position. In August 2025, ClonOrgan was part of a pig-to-human organ transplant, while other Chinese entities established an early lead in CRISPR-based cancer therapies.

The U.S. and China remain clear leaders in CRISPR research, and certain European countries are also active, but others are also rapidly building capacity. In April 2025, Brazil began the first patient trial of CRISPR gene editing for inherited heart disease, while growth has also been strong in Russia, India, and the Gulf States.

Concerns and Inevitability

The rapid adoption of CRISPR technology by private companies, institutions, ideologists, and hobbyists globally has drawn scrutiny. Despite the relatively low cost of developing CRISPR therapies, the actual treatments remain expensive. Social concerns have grown over the idea of “designer babies,” where wealthier families could immunize their children against diseases or select genetic traits, exacerbating inequality.

The He Jiankui case, for example, involved deleting the CCR5 gene in embryos to prevent HIV, but may have also improved their intelligence and memory due to the link between CCR5 and cognition.

Safety concerns also abound. Unintended downstream mutations, or “off-target effects,” can cause genetic defects or chromosomal damage, and in 2024, Swiss scientists documented such issues, highlighting the risks of heritable changes. Even DNA sequences once thought nonessential may have important functions, and edits could have unforeseen consequences for human evolution.

In 2015, a group of leading scientists and researchers proposed a global moratorium on heritable genome edits, yet research has pressed on. Sterilized, genetically modified mosquitoes were released in Africa to test population control in 2019, and in 2020, Imperial College London demonstrated that a “modification that creates more male offspring was able to eliminate populations of malaria mosquitoes in lab experiments.”

As with all emerging technologies, CRISPR-based therapies are resulting in major legal disputes. The Broad Institute, for example, holds patents for using CRISPR in human and animal cells, while UC Berkeley owns the original test-tube version, resulting in a patent battle settled in 2022. “The tribunal of the U.S. Patent and Trademark Office (USPTO) ruled that the rights for CRISPR-Cas9 gene-editing in human and plant cells belong to the Broad Institute of MIT and Harvard, not to Berkeley,” stated an article on the Cal Alumni Association website.

Biosecurity and weaponization concerns also constrain greater CRISPR adoption. Former U.S. Director of National Intelligence James Clapper repeatedly warned that genome editing, including CRISPR, could be used as weapons of mass destruction. Its ease of use has continued to raise fears of manipulating pathogens or making populations resistant to vaccines and treatments, as well as the potential to enhance cognitive or physical abilities in soldiers.

Still, the technology’s promise is too significant to be overlooked, as reflected by the attention it has received from Trump administration officials. Vice President J.D. Vance spoke positively about the CRISPR sickle cell treatment shortly after being elected. Other administration figures have financial ties to the industry, with disclosures showing Robert F. Kennedy Jr.’s plans to divest holdings in CRISPR Therapeutics AG and Dragonfly Therapeutics to avoid conflicts of interest before taking office.

New CRISPR tools, like base editing and prime editing, highlight the technology’s ongoing potential, and in 2025, Stanford researchers and collaborators linked these tools with AI to further augment their capabilities. While consolidation among companies and institutions grows, open-source labs may help drive a new frontier of innovation that heavily regulated business and bureaucratic organizations struggle to achieve.

CRISPR co-inventor Jennifer Doudna wrote in her 2017 book A Crack in Creation, “Someday we may consider it unethical not to use germline editing to alleviate human suffering.” With the potential to cure more diseases, some argue there is a moral obligation to reduce avoidable suffering even amid ethical objections. While companies have enormous financial incentives to bring these therapies to market, government oversight, private competition, and the eventual expiration of CRISPR patents, which allow for wider access and lead to lower costs, will be needed to ensure benefits are widely shared as they unfold.