Peter Schwarz

A social counterrevolution is developing in Europe, the likes of which has not been seen since the 1930s. Hundreds of thousands of well-paid jobs are being destroyed, alongside the dismantling of pensions, healthcare and social spending, upon which the livelihoods of millions of people depend. At the same time, enormous sums are being poured into armaments and war and into further enriching the already wealthy.

In its latest report on the economic situation in Europe, the International Monetary Fund calls for “deep cuts in the European model and the social contract” in order to plug the budget holes created by increased military spending and handouts to the banks during the financial and coronavirus crises. The report is aptly titled: “How Can Europe Pay for Things It Cannot Afford?”

An unprecedented jobs massacre is taking place in industry and, increasingly, in administration. Advances in electric mobility, information technology and artificial intelligence, which could greatly facilitate social life and solve social problems such as poverty and the climate crisis, are being used to increase profits and wage a bitter struggle for markets, raw materials and the redivision of the world—all at the expense of the working class.

This is not an economic downturn that will eventually be followed by an upswing but rather a structural crisis. The entire capitalist system is bankrupt. All the symptoms that led to fascism and two world wars in the last century are back: unrestrained speculation, the bitter struggle for raw materials and markets, trade wars, wars and dictatorship.

Germany at the center of the crisis

Germany, which accounts for almost a quarter of the economic output of all 27 EU members with a Gross Domestic Product of €4.3 trillion, is at the center of the crisis. What was long considered the strength of the German economy—its large share of exports and high foreign trade surpluses—is now proving to be its Achilles’ heel. Trump’s punitive tariffs and China’s rise as a high-tech producer are hitting it particularly hard.

Exports to the US slumped by 7.4 percent in the first nine months of this year. Trump has imposed tariffs of 15 percent on most imports from Europe, plus an additional 50 percent on metal components. As a result, many German cars and machines can no longer be sold in the US.

The country’s trade deficit with China has reached a record €87 billion this year. Between 2010 and 2022, German exports to China doubled, reaching a peak of €107 billion. Since then, they have fallen back to €80 billion, while imports from China continue to grow. For the first time, China is achieving a trade surplus this year not only in consumer goods but also in capital goods.

The market share of the three major German car manufacturers—Volkswagen, BMW and Mercedes—has fallen from 22.6 to 16.7 percent in China and from 21.7 to 19.3 percent worldwide over the past two years. The decline is even greater for electric cars.

Since 2019, the German economy has grown by only 0.3 percent. During the same period, the Chinese economy grew by 27 percent and the US economy by 12 percent, although growth in the US is largely based on speculative gains. The German Council of Economic Experts is predicting growth of just 0.9 percent for the coming year.

Corporations are passing on the full brunt of this crisis to the working class. In the industrial sector alone, 160,000 jobs have been destroyed in the last 12 months, or 3,000 per week. The three largest industries—mechanical engineering, auto and chemicals—which together employ more than 2.5 million people, are particularly affected.

According to a study by the German Economic Institute (IW), 55,000 jobs have been lost in the auto and supplier industry, which employs a total of 760,000 people, since 2019, with another 90,000 to follow by 2030. While large corporations, such as VW, Bosch and ZF, are cutting tens of thousands of jobs or gradually withdrawing from Europe, as Ford and Stellantis (Opel) are already doing, smaller suppliers are going bankrupt in droves.

Moritz Schularick, president of the Kiel Institute for the World Economy, doubts whether the three major German car manufacturers will even still exist in their current form at the end of the decade. This would affect over 600,000 jobs and hundreds of thousands more that depend directly or indirectly on them.

The situation is similar in mechanical engineering, which employs around 1 million people, many of whom manufacture highly specialized products for the global market. Here, production fell by 7 percent in 2024 and 5 percent in 2025. In the chemical industry, which employs 326,000 people, sales slumped by 10 percent in 2022 and 11 percent in 2023. The plants are now only operating at 71 percent capacity, with 82 percent considered profitable. The steel industry is facing complete liquidation, with 55,000 of the remaining 70,000 jobs under acute threat.

The only industry still growing in Germany is the arms industry. Over the next five years, Germany will invest a trillion euros into the business of death. Industry leader Rheinmetall increased its sales by 38 percent last year and by 30 percent this year. Its share price has risen twelvefold since 2022 and threefold since the beginning of this year.

While the livelihoods of workers and their families are being destroyed and entire regions are being deprived of their economic basis, the rich cannot get enough and continue to enrich themselves despite the crisis. There are now 3,900 people in Germany with assets in the hundreds of millions, an increase of 500 persons compared with a year ago.

Despite a slump in profits, job cuts and an urgent need for investment, Mercedes is buying back 2 billion euros worth of its own shares, thereby driving up its share price. While the company is cutting up to 20,000 jobs, the members of the board of directors are reaping double rewards: through the increase in their million-euro salaries linked to the share price and as owners of large blocks of shares. CEO Källenius alone owns around 50,000 Mercedes shares.

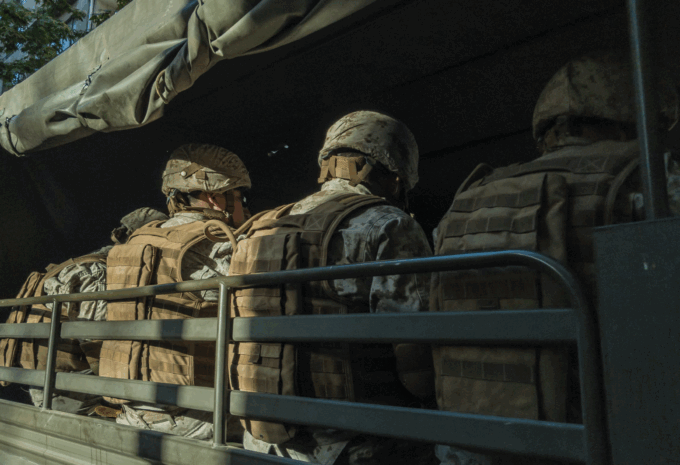

War at home and abroad

Germany’s ruling class is responding to the economic crisis with the same methods it used in the 1930s: by declaring war on the working class and returning to its criminal militarist traditions.

Ten years ago, the government had already announced that Germany sought to play a military role in the world in line with its weight as the third-largest economy. The Russian invasion of Ukraine, provoked by NATO, then served as a welcome pretext to put these plans into action.

The previous government led by Olaf Scholz (SPD) decided on a special fund of €100 billion for the rearmament of the Bundeswehr. The current government led by the Christian Democrat Friedrich Merz is providing 10 times that amount in loans and intends to build the strongest conventional army in Europe. By 2029 at the latest, this army should be capable of waging war against Russia. In that year, German military spending will have risen to €168 billion, about six times as much as at the beginning of the century.

Germany has spent €76 billion to date solely to support the war in Ukraine, making it the largest donor after the US. Its aim is not “defense” and “freedom” but rather economic dominance in Eastern Europe and Ukraine and the subjugation of Russia with its vast mineral resources, i.e., the same war aims Germany pursued in the First and Second World Wars.

The government is passing on the costs of this massive armament and war offensive to the working class, pensioners and the needy. This summer, Chancellor Merz announced that the welfare state in its current form was no longer financially viable. Economics Minister Katherina Reiche warns that pensions “will probably not be enough to live on later, despite high contributions.” She is calling for longer working lives and an “Agenda 2030”—a “comprehensive program based on the principle of more competition, and less government.”

Even maintaining the current pension level, which after 45 years of average contributions stands at 48 percent of an average salary—and thus well below the poverty line—is rejected by sections of the government.

The Financial Times cites the “dangerous illusion that generous social benefits can coexist with high productivity” as the cause of Germany’s malaise and urges it to set an example: Germany, “the anchor of budgetary discipline and industrial strength on the continent,” must “teach Europe how to face the truth about welfare states—before they collapse under their own weight.”

Socialist perspective

The onslaught against jobs, pensions and social gains won by the working class after World War II is in full swing worldwide and is meeting with increasing resistance.

In France, President Macron is sticking to his pension reform, even though mass protests have forced him to replace his prime minister five times. The hated “president of the rich” remains in office only because the Socialists are backing him. In Italy, Belgium and Portugal, general strikes and mass protests against social cuts and austerity budgets will take place in the coming weeks.

In the US, President Trump is cutting social benefits on which millions depend. American companies have announced 1.1 million layoffs this year. In China, millions of jobs have been lost in recent years to automation and the crisis in the construction industry, and youth unemployment in cities stands at 19 percent. In African and Asian countries, Generation Z has been protesting for three years against the lack of any prospects for the future.

This movement of the international working class and youth, however, lacks a viable perspective.

The corporatist trade unions, which used to negotiate social compromises within the framework of “social partnership,” have become the spearhead of social cuts and mass layoffs. In Germany, the trade union federation (DGB) and its works councils develop layoff plans within the framework of legally regulated “co-determination” and suppress resistance to the layoffs. Union bureaucrats sit on company supervisory boards and often move on to the executive.

The reason for this is not only the—undoubtedly widespread—corruption of highly paid union officials and works council members but the nationalist perspective upon which the unions are based. This perspective is geared toward strengthening the competitiveness of their “own” companies because, according to union logic, this is the only way to preserve jobs.

On this basis, the unions agree to job cuts, wage reductions and poorer working conditions. They play one location off against another, divide workers from their colleagues in other countries and boycott any serious resistance. A typical example of this is the so-called bidding war between the Ford plants in Saarlouis, Germany and Almussafes, Spain in which the works councils undercut each other with concessions until both plants were largely shut down.

The unions also support their government’s respective war policies. Whereas the IG Metall union used to promote the slogan “swords to plowshares,” it now advocates converting auto factories into tank factories.