Abdus Sattar Ghazali

Gabriel Zucman, the author of the 2015 book “The Hidden Wealth of Nations: The Scourge of Tax Havens,” estimates that $7.6 trillion is stashed in tax havens. This amounts to 8 percent of the world’s personal financial wealth. The author believes that if all of this illegally hidden money were properly recorded and taxed, global tax revenues would grow by more than $200 billion a year.

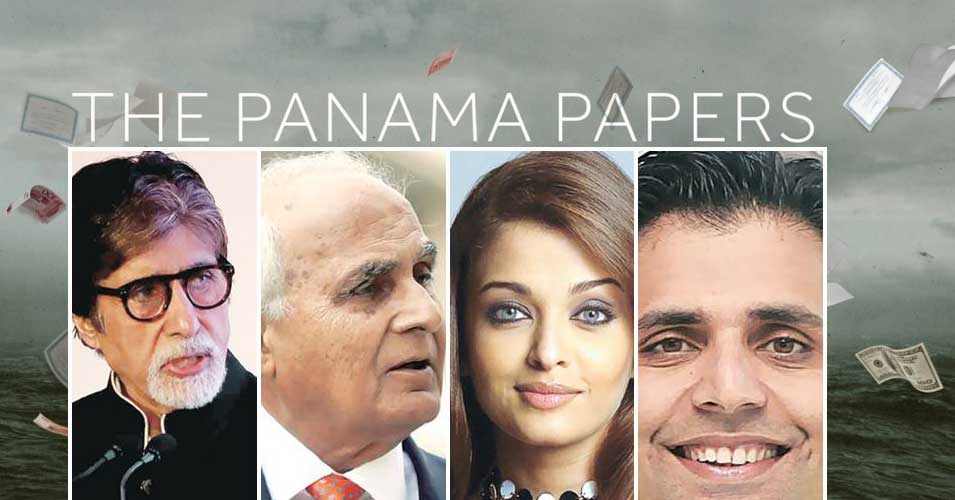

Interestingly, on April 3, 2016, the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, leaked massive documents known as “Panama Papers” which reveal the shadowy world of hidden offshore finances of presidents and prime ministers. The biggest leak of financial data in history exposes the offshore holdings of 12 current and former world leaders and provides details of the hidden financial dealings of 128 more politicians and public officials around the world.

The German newspaper, Süddeutsche Zeitung (SZ), which worked on the leaked documents with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, said the data provides rare insights into a world that can only exist in the shadows. It proves how a global industry led by major banks, legal firms, and asset management companies secretly manages the estates of the world’s rich and famous: from politicians, FIFA officials, fraudsters and drug smugglers, to celebrities and professional athletes.

According to The Guardian, the Panama Papers are an unprecedented leak of 11.5m files from the database of the world’s fourth biggest offshore law firm, Mossack Fonseca. The documents show the myriad ways in which the rich can exploit secretive offshore tax regimes. The massive leak of confidential documents from a Panamanian law firm has shown how some of the world's richest people hide assets to avoid paying taxes.

Among national leaders with offshore wealth are Nawaz Sharif, Pakistan’s prime minister; Ayad Allawi, ex-interim prime minister and former vice-president of Iraq; Petro Poroshenko, president of Ukraine; Alaa Mubarak, son of Egypt’s former president; and the prime minister of Iceland, Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson.

Pakistan Prime Minister Nawaz Sharif has formed a high-level judicial commission to probe any financial wrongdoing, a day after three of his children were named in the 'Panama Papers' for owning offshore companies prompting demands for an enquiry by the opposition. Documents on the ICIJ website said Sharif's children - Mariam, Hasan and Hussain - "were owners or had the right to authorize transactions for several companies". Punjab Chief Minister Shahbaz Sharif’s relatives Samina Durrani and Ilyas Mehraj have also figured in the documents examined.

Iceland’s prime minister, Sigmundur Davíð Gunnlaugsson, became the first major casualty of the Panama Papers, stepping aside from his office amid mounting public outrage that his family had sheltered money offshore.

A $2bn trail leads all the way to Vladimir Putin’s best friend Sergei Roldugin who is at the centre of a scheme in which money from Russian state banks is hidden offshore. A spokesman for Russian President Vladimir Putin told The Guardian that the media investigation into offshore accounts is motivated by “Putinphobia,” and that he has not been implicated in any wrongdoing.

Putin’s spokesman Dmitry Peskov said “it’s obvious that the main target of such attacks is our president,” and claimed that the publication was aimed at influencing Russia’s stability and parliamentary elections scheduled for September. He suggested the Washington-based International Consortium of Investigative Journalists, which co-ordinated the international investigation, has ties to the U.S. government.

Family members of at least eight current or former members of China’s Politburo Standing Committee, the country’s main ruling body, have offshore companies arranged though Mossack Fonseca. They include President Xi’s brother-in-law, who set up two British Virgin Islands companies in 2009. China’s foreign ministry dismissed reports of the leaks from the Mossack Fonseca database as ‘groundless accusations’. A Communist party censorship directive instructed news organizations to purge all reports, blogs, bulletin boards and comments relating to Panama Papers revelations.

Twenty-three individuals who have had sanctions imposed on them for supporting the regimes in North Korea, Zimbabwe, Russia, Iran and Syria have been clients of Mossack Fonseca. Their companies were harbored by the Seychelles, the British Virgin Islands, Panama and other jurisdictions.

Tax Havens

Jill Lawless of the Associated Press says there's one part of the British Empire on which the sun still does not set: its tax havens. Britain's former world dominance has left it with a string of tiny territories scattered around the globe, and many of them have become hubs for hiding money. Despite growing political pressure, shutting down these and other tax havens may be easier said than done, Jill said.

As Britain's colonies gained independence after World War II, London encouraged several small Caribbean islands to become tax havens as a means to self-sufficiency. As a result, many of the world's tax havens have British links, including overseas territories such as the British Virgin Islands, Bermuda and the Cayman Islands. The Channel Islands of Jersey and Guernsey off the French coast, which are possessions of the British Crown, have been havens for the wealthy and their money for almost a century.

More than half the 200,000 companies set up for clients by Panamanian firm Mossack Fonseca in the leaked files are registered in the British Virgin Islands, a British overseas territory in the Caribbean.

According to the BBC two broad qualifications for being a tax haven are to have a low or zero rate of income tax and guarantee the rich a cloak of secrecy they would not receive in their own country. They have also been used to cover up criminal activity.

Since 2009, many attempts have been made to crack down on abuses. More than 700 tax transparency deals have been signed globally. Places including Switzerland, the Channel Islands and Luxembourg have tightened the rules, but Panama and the British Virgin Islands are among those criticized for not doing enough. The Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development and the Group of 20 nations have persuaded more than 90 countries to share financial data in a bid to crack down on secret dealings.

Mossack Fonseca

The Panama Papers make it clear that major banks are big drivers behind the creation of hard-to-trace companies in the British Virgin Islands, Panama and other offshore havens. They list nearly 15,600 paper companies that banks set up for clients who want keep their finances under wraps, including thousands created by international giants UBS and HSBC.

Mossack Fonseca is one of the world’s top creators of shell companies, corporate structures that can be used to hide ownership of assets. The law firm’s leaked internal files contain information on 214,488 offshore entities connected to people in more than 200 countries and territories.

The offshore system relies on a sprawling global industry of bankers, lawyers, accountants and these go-betweens who work together to protect their clients’ secrets. These secrecy experts use anonymous companies, trusts and other paper entities to create complex structures that can be used to disguise the origins of dirty money.

The Mossack Fonseca law firm has worked closely with big banks and big law firms in places like The Netherlands, Mexico, the United States and Switzerland, helping clients move money or slash their tax bills, the secret records show.

Big U.S. firms hold $2.1 trillion overseas to avoid taxes

Not surprisingly, in October 2015, an economic study revealed that the 500 largest American companies hold more than $2.1 trillion in accumulated profits offshore to avoid U.S. taxes and would collectively owe an estimated $620 billion in U.S. taxes if they repatriated the funds.

The study, by Citizens for Tax Justice and the U.S. Public Interest Research Group Education Fund, found that nearly three-quarters of the firms on the Fortune 500 list of biggest American companies by gross revenue operate tax haven subsidiaries in countries like Bermuda, Ireland, Luxembourg and the Netherlands.

Apple was holding $181.1 billion offshore, more than any other U.S. company, and would owe an estimated $59.2 billion in U.S. taxes if it tried to bring the money back to the United States from its three overseas tax havens, the study said.

General Electric has booked $119 billion offshore in 18 tax havens, software firm Microsoft is holding $108.3 billion in five tax haven subsidiaries and drug company Pfizer is holding $74 billion in 151 subsidiaries, the study said.

"At least 358 companies, nearly 72 percent of the Fortune 500, operate subsidiaries in tax haven jurisdictions as of the end of 2014," the study said. "All told these 358 companies maintain at least 7,622 tax haven subsidiaries."

Fortune 500 companies hold more than $2.1 trillion in accumulated profits offshore to avoid taxes, with just 30 of the firms accounting for $1.4 trillion of that amount, or 65 percent, the study found.

In September 2015, a U.S. federal judge authorized the Internal Revenue Service to seek the names of Americans using accounts at two Belize banks.